WASHINGTON — A new study is raising questions about when ancient human ancestors in Europe learned to control fire, one of the most important steps on the long path to civilization.

A review of 141 archaeological sites across Europe shows habitual use of fire beginning between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago, according to a paper in today’s edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Most archeologists agree that the use of fire is tied to colonization outside Africa, especially in Europe where temperatures fall below freezing, wrote Wil Roebroeks of Leiden University in the Netherlands and Paola Villa of the University of Colorado.

Yet, while there is evidence of early humans living in Europe as much as a million years ago, the researchers found no clear traces of regular use of fire before about 400,000 years ago.

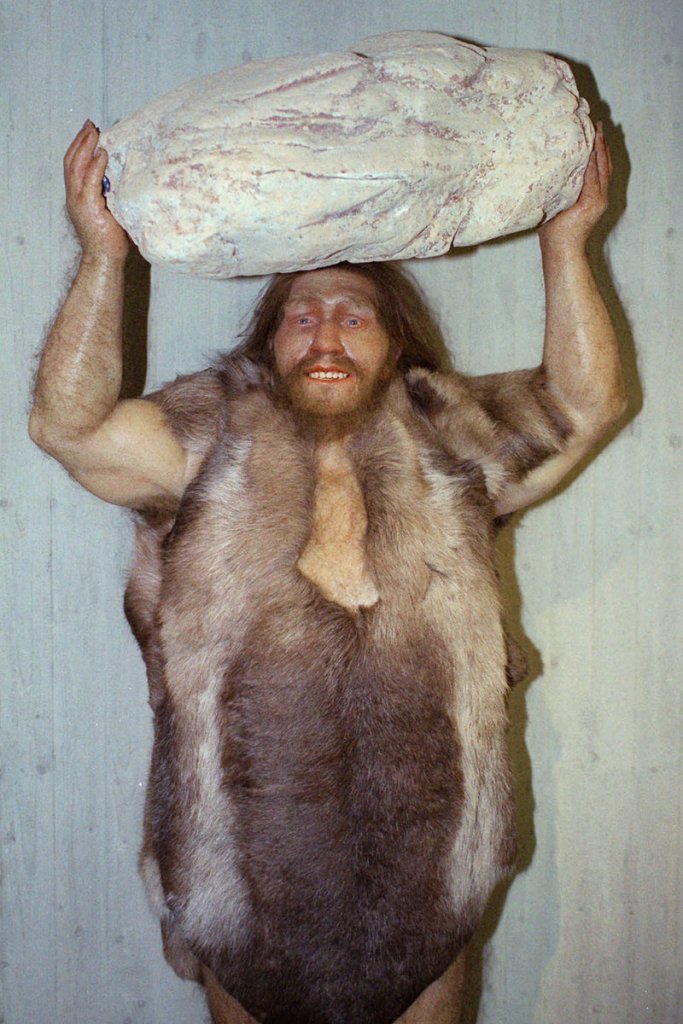

After that, Neanderthals and modern humans living in Europe regularly used fire for warmth, cooking and light, they found.

“The pattern emerging is a clear as well as a surprising one,” they said, considering these ancient people were living in the cold European climate.

Their results raise the question of how early humans survived cold climates without fire.

The researchers suggest a highly active lifestyle and a high-protein diet may have helped them adapt to the cold, adding that the consumption of raw meat and seafood by hunter-gatherers is well documented.

Before that period, there is a single site in Israel with earlier evidence of regular fire use, the researchers noted, and there are sites in Africa indicating sporadic fire use.

Not so sure of the late date for controlling fire is Harvard archaeologist Richard W. Wrangham, author of the book “Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human,” who argues that learning to cook food — perhaps as much as two million years ago — improved nutrition enough for a burst of evolution promoting development of a bigger brain and, eventually, leading to modern humans.

Wrangham suggested that the lack of earlier evidence of fire could merely mean that, over time, the burned bones or ashes had been destroyed or dispersed.

But Villa, in an interview, said that there is evidence of burned bones in a South African cave from a million years ago, “so burned bones do preserve.”

“This paper represents very clearly the archaeological conclusions to what Wil Roebroeks has elegantly called a case of ‘science friction’ resulting from the clash between archaeological and biological evidence,” Wrangham wrote in an e-mail.

“So either way we have a lovely puzzle,” he said.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.