SOUTH PORTLAND — A colorful bouquet was placed near an unmarked grave in Forest City Cemetery last month.

Beneath the freshly dug earth lay the remains of Howard Mansfield III. His body was found March 3 in his apartment in Portland’s East Bayside neighborhood. At the age of 51, he died, alone. His death certificate says, “pending further studies.”

No one purchased an obituary in the days after his death, and no headstone was placed on his grave. The only public record of Mansfield’s passing was a small death notice, published in The Portland Press Herald on March 8, the day after his funeral.

No family or friends attended the service.

Two funeral directors and three cemetery workers buried him. Tim Chalmers, a funeral director at Hobbs Funeral Home, recited Psalm 23, a prayer often associated with funeral liturgies.

“I didn’t have to say a prayer, but I felt like something should be said,” Chalmers said. “He deserves a dignified burial and respect paid to him, just like everyone else.”

Howard Mansfield wasn’t just like everyone else. He was one of a small but growing number of “city cases”: homeless, transient or poor people from Portland who die without the money to pay for their own funerals. Some have no families, while others are estranged from those who were once close to them.

When they die, taxpayers foot the bill.

Since January 2009, the city has paid for 61 burials in Portland’s two major municipal cemeteries: Evergreen Cemetery on Stevens Avenue and Forest City Cemetery off Broadway in South Portland.

There were 12 city cases in 2009, 22 in 2010, and 18 in 2011. Nine have been buried so far this year, setting the pace for a record number of 25 to 30.

Those figures represent nearly 10 percent of the city’s 630 burials over the past three years.

Joe Dumais, Portland’s parks and cemeteries coordinator, said the cemetery staff handles city cases with the same level of sensitivity and respect as burials of the affluent or prominent dead.

“This is the final resting place for a person,” Dumais said. “Our mission is to make sure this is done with dignity and respect. Who they are in life is important to someone. I assure you that the gentleman we buried got the same level of service from us as the guy next to him did.”

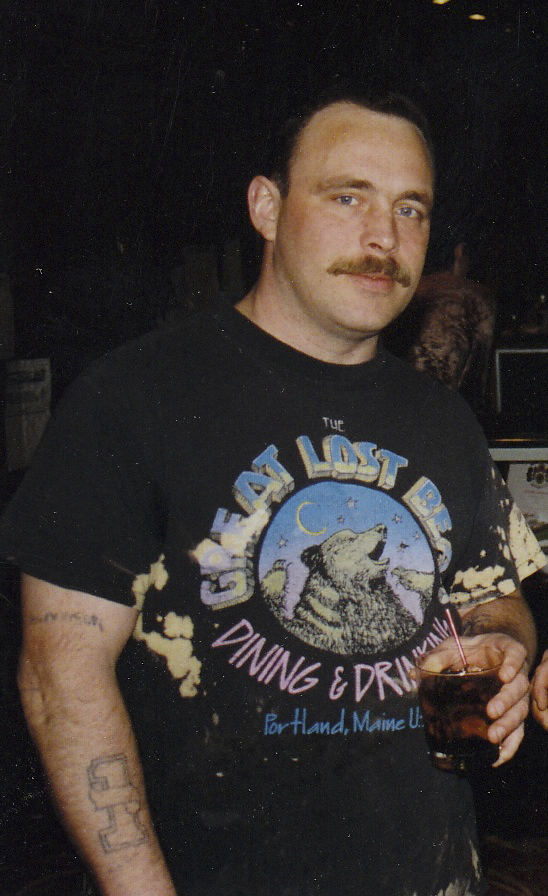

Mansfield had worked in restaurants in Portland for the past 10 to 15 years, including the Great Lost Bear on Forest Avenue and, most recently, at DiMillo’s on the Portland waterfront, where he was the head prep cook. Former co-workers and supervisors said he was loyal, dependable and well-liked by the staff.

“Howard was usually one of the first ones here and the last to leave,” said Fred Breton, a kitchen manager at DiMillo’s. “He always made sure his work was done and was done properly.”

Steven DiMillo, the restaurant’s owner, said Mansfield had a great attitude at work.

“All of his co-workers liked him,” DiMillo said. “He had a dry sense of humor. He didn’t talk much, but when he did, he was intelligent. It was a good, light-hearted conversation.”

But Mansfield struggled with alcoholism. From the late 1970s through the mid-1990s, he was arrested 12 times and served multiple short stints in jail, for mostly petty offenses fueled by his drinking.

It was a life that separated Mansfield from his family, emotionally if not physically.

‘KIND OF A DRIFTER’

He had sisters in Greater Portland, but they were out of touch and police could not locate them after his death.

The family learned of Mansfield’s death from a reporter, who identified them from an obituary published when one of his sisters, Sally Prindall, died in 2006.

Prindall’s husband, Bruce Prindall of Durham, said the last time he saw Mansfield was at his wife’s funeral.

He said Mansfield grew up in the Yarmouth area as one of five children. His mother was a single parent who struggled to support her kids. At 12 years old, he was sent to live at Opportunity Farm, a social service organization in New Gloucester that provides safe, supportive, family-style homes for at-risk young people.

Mansfield then became a “carny.” He operated amusement rides for Smokey’s Greater Shows, one of the area’s traveling carnivals, for many years.

“At one point, I was going to bring him in to live with us, but some of his habits didn’t fit our lifestyle,” Prindall said. “If someone could have grabbed him and took him under their wing, it would have been good. It was a really tough situation.”

Janet Cote, a sister who lived on Gay Street, fewer than two miles from Mansfield, learned of Mansfield’s death from Bruce Prindall.

Cote remembered her brother as a kind and friendly person who liked to play darts and ride his bicycle. He isolated himself from his family and friends, she said.

“He was kind of a drifter. That’s the best way to explain my brother,” Cote said. “He liked to live in the shadows. That’s just the way he was.”

CITIES IN COMPARISON

Portland has its share of people like Mansfield, folks who are marginalized and defeated by alcohol, drugs or other hardships. The city has an extensive network of public and private social services to meet their needs. That may explain why the number of city burials climbed during the recession, and why Portland seems to have a relatively high number of burials conducted at taxpayer expense.

The city of Nashua, N.H., which has a population of 87,735, has handled one case a month since December. The smaller Concord, N.H., averages one to two burials of indigent people each year. The same goes for Burlington, Vt.

In Maine, Lewiston handles one to two cases a year. Bangor buries its homeless people in Municipal Cemetery at Mount Hope in the “welfare section.” The city handles 10 to 12 cases each year. Only a couple of those people are buried; the rest are cremated.

“For the number of people we serve through General Assistance, I don’t think it’s particularly high for a population of 32,000,” said Shawn Yardley, director of health and community services for the city of Bangor. “I think it’s tragic that we have to bury anyone because they don’t have family members that are able to do that.”

Portland taxpayers spent $745 for Mansfield’s burial plot, the going rate for space at Forest City, and another $790 for the burial, which includes the concrete vault inside the grave.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, a traditional funeral, including a casket and vault, costs about $6,000, and “extras” such as flowers, obituary notices, acknowledgment cards or limousines can add thousands of dollars to the bottom line. Many funerals run well over $10,000. In Maine, the average cost of a funeral is about $7,500.

City cases are paid for by General Assistance, which is mostly state-funded and provides emergency help to people in need.

In Portland, the General Assistance budget for fiscal year 2011 was $6.4 million.

The city last year spent $85,000 to pay for the burials at the two cemeteries, and for others who were cremated, 49 indigent people in all. City officials estimate it will handle 50 cases this year at a cost of $67,000. If all the deceased were buried, the cost would climb to roughly $90,000.

Funeral homes are typically reimbursed a fraction of the cost for a city burial. Those cases are handled on a rotation among five funeral homes in the Portland area.

NO GRAVE MARKER – YET

Jones-Rich-Hutchins Funeral Home in Portland is on the list.

Robert Barnes, vice president of the funeral home, said Friday that the funeral home receives a handful of city cases each year. He said with cases like Mansfield’s — when no family comes forward to claim the body — funeral directors will often say the Lord’s Prayer or another prayer to honor the deceased.

“It’s a sad case when you have that happen,” Barnes said. “The individual was raised by a family. They were loved or cared for. … They were here on this Earth. I am a caretaker for that person, and it’s my responsibility to place him at a respectful place of rest. It gives me a sense of fulfillment.”

Mansfield was laid to rest in a wooden and cardboard “cremation tray” that cost $155. His grave is in section CC Lot 522 at Forest City. There is no headstone. His final resting place is identified only by a number, etched in a round metal marker that is driven into the ground. That’s enough to find the grave among the 30,000 at Forest City.

“We know exactly where he is,” said Dumais, the cemeteries coordinator. “If someone wanted to locate him, we could.”

Whether anyone in his family will ever want to locate Mansfield remains to be seen.

Cote, his sister, said she has not been to her brother’s grave. She said Friday that her family was trying to get together to hold a service for him. A small paid obituary for Mansfield appeared in The Portland Press Herald on March 29, 26 days after his death.

A group of Mansfield’s co-workers from DiMillo’s visited the cemetery a week or so after he was buried. Several said they would have attended his funeral, but the death notice wasn’t published until the day after his burial. Employees at the restaurant are now raising money to buy a plaque for his grave.

“Howard deserves it,” said Melissa Bouchard, a chef at DiMillo’s, who worked with him on and off for the past seven years. “I considered Howard a friend and a very important part of my kitchen team. I thought the world of Howard. I thought he was a good guy. I just can’t imagine him being forgotten.”

No one seems to know who put the flowers on his grave.

Staff Writer Melanie Creamer can be contacted at 791-6361 or at: mcreamer@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.