What’s wrong with this picture?

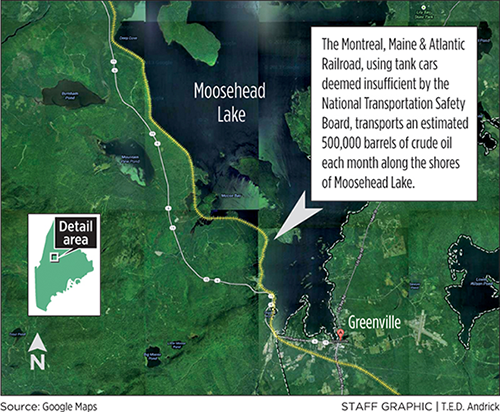

The Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway, virtually unknown to many Mainers before one of its crude-oil trains obliterated part of the Canadian border town of Lac-Megantic last weekend, runs hard by the western shore of picturesque Moosehead Lake.

The half-million barrels of North Dakota light crude that pass within 50 feet of those pristine waters each month is transported via the DOT-111, a type of tank car that carries as much as 34,500 gallons of oil, to an Irving Oil refinery in St. John, New Brunswick.

According to the National Transportation Safety Board, the “inadequate design” of the DOT-111 for crude-oil transportation makes it “subject to damage and catastrophic loss of hazardous materials” in a derailment.

In other words, if a train were to wreck by the edge of Moosehead Lake, a crown jewel of Vacationland’s tourism economy, some if not all of those DOT-111s likely would rupture, and Maine would have an environmental disaster.

Worse yet, if the same cars containing the same volatile crude oil were to derail along Pan Am Railroad tracks through Portland, Lewiston or Bangor, we’d no longer be safely insulated by an international border from the daily scenes of death and destruction in southern Quebec.

“We cannot abdicate our responsibility to learn from this and make sure those lives were not lost in vain,” said House Majority Leader Seth Berry, D-Bowdoinham, referring to a death toll in Lac-Megantic that’s now expected to go as high as 60. “We need to really drill down and ask some tough questions.”

Starting with this one: How can two railroads be traversing Maine daily with what are essentially rolling oil pipelines made up of tank cars that the nation’s top safety agency has long considered unsafe for the task?

The NTSB most recently sounded the alarm about the DOT-111 in 2009, after the derailment of a Canadian National Railway train carrying highly flammable ethanol. Of the 19 cars that derailed, 13 ruptured and caught fire at a rail crossing in Cherry Valley, Ill. — killing one person, injuring nine and causing an estimated $7.9 million in property damage.

In setting its investigatory sights on the DOT-111, the NTSB cited the tank car’s “poor performance” in four other derailments: Superior, Wis., in 1992; Tamaroa, Ill., in 2003; New Brighton, Pa., in 2006; and Arcadia, Ohio, in 2011.

The agency’s conclusion: “Clearly, the heads and shells of DOT-111 tank cars … can almost always be expected to breach in derailments that involve pileups or multiple car-to-car impacts.”

The good news is that as of late 2011, industry standards for new DOT-111s include thicker steel shells and stronger, better-protected fittings designed to withstand a crash without rupturing and spewing their hazardous cargo.

The bad news is that efforts by the NTSB to retrofit the nation’s fleet of about 200,000 older DOT-111s with the added protections is going nowhere fast. A proposed rule change before the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, open to public comment until Sept. 17, has met stiff resistance from the Association of American Railroads.

Association spokeswoman Patricia Reilly told the media this week there are “technical difficulties” with the retrofitting requirement. Meaning, essentially, it would cost too much.

So where does that leave Maine, where the number of barrels of crude transported by rail has exploded from zero in 2010 to 25,319 in 2011 and 5,237,097 in 2012? (The 2013 total, according to figures on file with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, was on track to exceed 10 million barrels before last weekend’s disaster.)

Late Tuesday night, House Majority Leader Berry’s 11th-hour effort to launch a legislative study of Maine’s vulnerability to a crude-oil train wreck passed in the House on a partisan vote, but was tabled in the Senate amid concerns it was too soon to study anything. That fight, Berry said Thursday, is not over.

“What I proposed was simply a review by the (Legislature’s) Transportation Committee,” Berry said. “I want them to look at the environmental and public-safety components of all this.”

Gov. Paul LePage, much to his credit, has ordered the Maine Department of Transportation to obtain all safety and inspection reports on Maine’s railroads from the Federal Railroad Administration, and “utilize information as it becomes available on the cause of the Quebec train derailment to reassess the safety of Maine’s rail infrastructure and take appropriate action to mitigate any safety concerns.”

“This is us doing some data mining with the Federal Railroad Administration,” said Ted Talbot, spokesman for the Department of Transportation. Much like the federally regulated trucking industry, he noted, Maine’s railroads operate each day without the state knowing “what they’re hauling, when they haul it or their destinations.”

That said, Talbot cautioned, “any and all discussion on changing the process begins and ends with the federal government.”

Thus we can only sit with crossed fingers as those long lines of oil-laden DOT-111s, unsafe as they are, snake their way through Maine’s most populated and environmentally precious areas.

And while we’re on the subject of federal oversight, we can only smack our foreheads over the fact that the feds have one — and only one — inspector keeping an eye on the state’s 1,100 miles of railroad.

Finally, we have the Maine DEP, which began meeting with railroad representatives in November — a full year after the railroads got into the crude-oil transportation business in a big way — to talk potential disasters.

Which brings us back to postcard-perfect Moosehead Lake, now at the height of its summer tourist season. What would happen if a train full of oil suddenly went off the tracks and began spewing countless gallons of crude directly into Maine’s largest body of fresh water?

“Obviously, the first responders would go from the local fire department and then we would be called,” replied DEP spokeswoman Jessamine Logan. “We have booming equipment in Portland, Augusta and Bangor.”

It would take two hours or more to get that equipment to Moosehead from Augusta or Bangor, which is at least better than the three-hour drive from Portland.

“That is why we developed the work groups,” noted Logan. “To find out if and where we need to stage equipment.”

Leaving only the question of when.

Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at bnemitz@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.