Joseph Herrick deserves better.

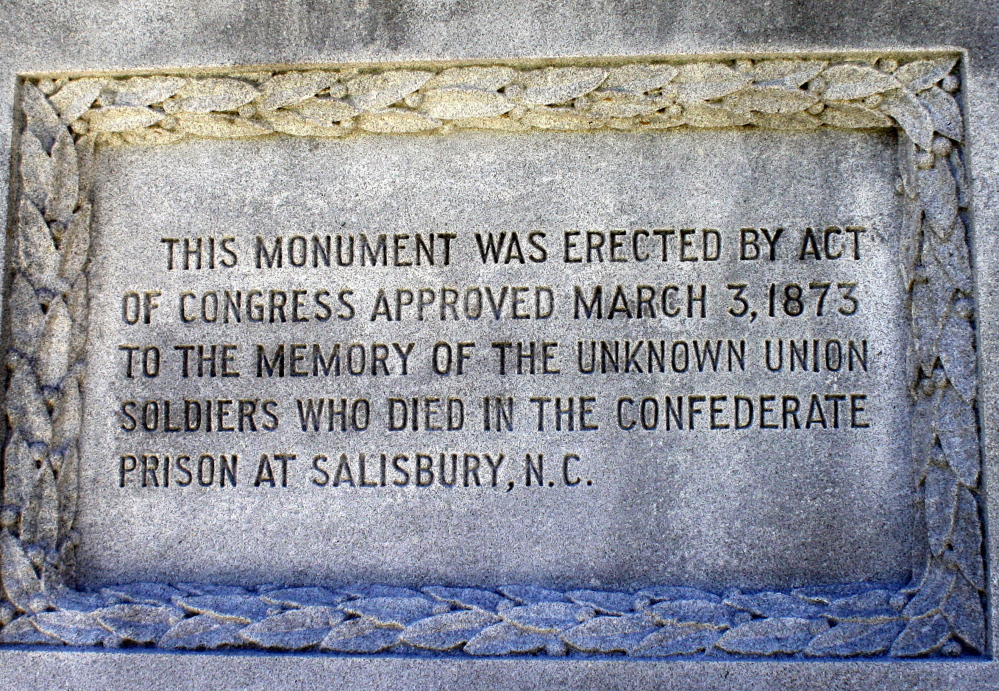

Herrick is one of about 200 Maine Civil War soldiers whose remains lie in unmarked graves, a series of trenches dug to hold the bodies of those who died in a Confederate-run prison in Salisbury, N.C.

Herrick exemplified traits that Mainers hold dear: hard work in farm and forest, family, grit and self-sacrifice.

Herrick’s great-great-grandniece, Tracey McIntire, would like to know why, 150 years after Herrick’s death, the federal government still refuses to name Herrick and Maine’s other soldiers on a memorial on the site.

The Maine soldiers, most of whom were trained in Augusta as part of the Union’s Maine 32nd Infantry 150 years ago, are one portion of a larger group of thousands of veterans.

McIntire, who today lives in Boonsboro, Maryland, grew up in Massachusetts and New Hampshire and had family in Maine.

“Just to go through that hell on earth and then get dumped in a trench and then no recognition, it just … it breaks my heart,” McIntire said. “I just want his name to be remembered. He made the ultimate sacrifice.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs says that it can’t erect a headstone at the prison site, now Salisbury National Cemetery, because only a person’s proven next-of-kin can apply for a marker.

“It doesn’t really allow for genealogical research alone,” said Josephine Schuda, a spokeswoman for the Veterans Affairs.

McIntire said the rules might be appropriate for recently deceased veterans, but it amounts to an impossible barrier for people like her, who want to honor a relative from the bloody conflict that left 600,000 soldiers dead.

“I’ve got all this proof. I’ve got my family tree to show that I’m related. There are no direct descendants,” McIntire said.

She said she has called the VA, as well as her congressmen and senators, without results.

“I don’t know what else they want,” she said. “I’ve just hit a stone wall as far as action goes.”

The regulation requiring next-of-kin is meant to prevent situations that would cause families pain, according to the VA.

“Adherence to this regulatory definition is intended to avoid the possibility that a person lacking familial relationship to the Veteran may alter the Veteran’s gravesite in a manner not desired by the Veteran’s family,” wrote Steve L. Muro, undersecretary for memorial affairs of the Department of Veterans Affairs, in a March 24 letter in response to a request for information by the Morning Sentinel.

Muro said the VA could change the policy and that the definition of next-of-kin “may be too limiting, and we are reviewing the current regulation to include the applicant definition.”

The Civil War still seems close at hand to McIntire. She has memories of her grandfather, who in turn had clear memories of his grandmother, Herrick’s sister.

Herrick’s anonymous remains are not alone.

SOUTH HELPS NORTH

Civil War historian Mark Hughes, whose ancestors died fighting Herrick’s comrades, said his first clear memory of a Civil War cemetery came in Richmond when he was just 8 years old.

“On one of the headstones instead of a name, it said unknown,” he said. “I asked my mother who was buried there, and she said, ‘Honey, nobody knows.’ And I thought that was a shame.”

Two of Hughes’ own ancestors were killed by the Union Army and another was wounded, but he still feels the Union men in the ground at Salisbury should be recognized.

“I care because they’re American soldiers who fought for their country,” Hughes said.

THE EARLY YEARS

McIntyre has pieced together the tragic details of Herrick’s life through visits to the National Archives and digitally scanned documents.

Herrick was born to Henry and Ruth Herrick in January 1845 in Greenwood. He had 14 brothers and sisters. The family was very poor. They owned a couple of cows, but no land.

When the war first began in 1861, Herrick was a teenager. His father, 43, a member of Maine’s 14th Regiment, was wounded and permanently disabled, but the federal government denied his disability claim, based on a pre-existing condition.

“Everything fell on Joseph’s shoulders to support his parents,” McIntire said.

The temptation to enlist would have been tremendous, because it carried a signing bonus of $300, a huge sum at the time.

In March 1864, at 19, he enlisted in nearby Norway. He would never see 20. He used the $300 to make a down payment on a farm for his family.

TO THE BATTLEFIELD

If Herrick had any dreams of battlefield glory, they were short-lived.

Although he survived the disastrous Battle of Cold Harbor, which began on the last day of May 1864., he soon fell deathly ill with chronic diarrhea, a common and serious ailment for soldiers of that era.

He was shipped to a hospital in D.C. and then returned to the front lines just before the Sept. 30 Battle of Peebles’s Farm.

That battle went better for the Union army, which gained ground, but worse for Herrick, who was one of four men from Company G captured by the Confederates.

PRISON AND DEATH

At overcrowded Salisbury Prison, Herrick suffered a relapse of diarrhea and died on Nov. 22.

“They had what they called the dead house,” McIntire said. “They would bring the dead in, take whatever valuables off them, put them in a cart and then take them to this mass burial site. ”

McIntire has paid to have Herrick’s name included on a wall at Pamplin Historical Park, a Civil War museum in Petersburg near the site of the battle in which he was captured.

She joined the Salisbury Prisoners Association, which keeps the memory of the soldiers there alive.

It helps, but it is inadequate, she said.

“He’s not buried at Petersburg. He’s buried in Salisbury. It’s like anybody would feel if your ancestor is in an unmarked grave.

“I would like to have his name up there. But I’m not holding my breath.”

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287

mhhetling@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.