They say true love waits, but at 91, Real L’Heureux didn’t want to wait any longer.

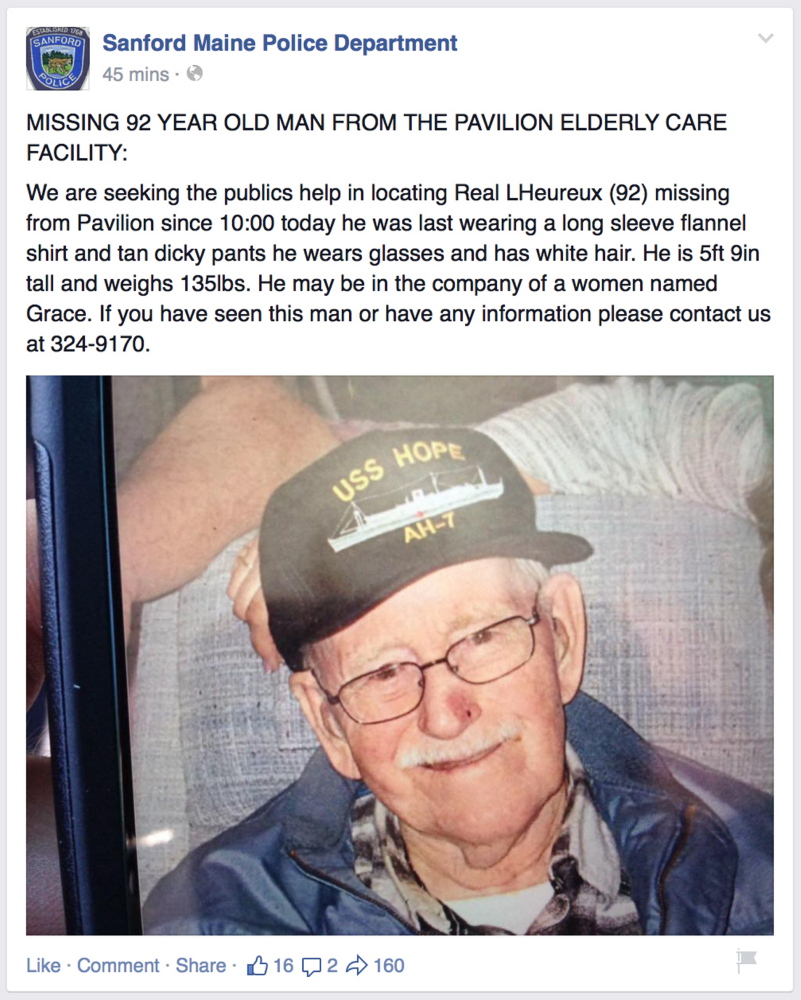

At some point before noon on Tuesday – against the wishes of his doctors, his family and the court – the thin, French-speaking World War II veteran absconded from the locked Alzheimer’s and dementia care facility in Sanford where he lives, perhaps through a window, and took off walking, determined to be with the woman he loves.

When 77-year-old Grace Harakles’ phone rang, she couldn’t believe it.

Come pick me up, L’Heureux told her. “I’m out.”

For several hours on Tuesday, Sanford police and the staff from the Pavilion at Sanford Medical Center searched for L’Heureux, checking woods and looking in bodies of water.

Around 4 p.m., Sanford Police Chief Thomas Connolly located L’Heureux at Harakles’ house, a mile and a half from the center, and confirmed he was not in any danger. With no power to remove L’Heureux, Connolly let the couple be.

“He was argumentative and feisty and didn’t want to leave,” Connolly said. “It’s up to his family to figure out how best to get him back to the facility.”

The staff at the hospital isn’t yet sure exactly how L’Heureux got out, and L’Heureux’s lips were sealed.

“I don’t care where you are, if you want to get out, you find a way to go out,” L’Heureux said in an interview at Harakles’ home as police waited outside. “I don’t want to go back.”

While the story of L’Heureux and Harakles’ relationship can be seen as a heart-warming tale of separated lovers, his escape and desire to elope highlights an increasingly common predicament for adult children who have aging parents. They must navigate the fraught process of persuading their parents to surrender some of their independence in exchange for safer, predictable lives in assisted-care facilities.

Matters get even more complicated when an aging person’s desire for romance conflicts with the need to protect the assets that will pay for their care.

“The issue is, at what point do we lose our right to make bad decisions?” said Barbara Schlichtman, an attorney with the Maine Center for Elder Law.

Schlichtman is not involved in L’Heureux’s case, but deals frequently with issues of estate planning and aging. Uncomfortable as it might be, when a parent or relative begins to lose the ability to make sound decisions, the family must sometimes use the court system to intervene.

“We have the right to spend money foolishly, we have the right to date someone who’s bad for us,” she said. “As someone ages, at what point does the balance tip that they’re in imminent harm, and they lose the right to make bad decisions?”

For L’Heureux, who’s been diagnosed with mild dementia, the power to make decisions about his future was taken out of his hands in March 2014, when his daughter Adele Carroll was granted guardianship of her then-90-year-old father. That gave her power to decide where he lives, who cares for him and, in some cases, with whom he may associate, according to court documents.

None of L’Heureux’s children could be reached for comment Tuesday, but a man who answered the phone at a family member’s home said none of his relatives wanted to comment. Carroll and a sibling have spelled out their concerns for their father and about Harakles in court documents.

L’Heureux protested, saying that he was capable of caring for himself, and that his family was out to get his money. Carroll alleged that it was Harakles who wanted L’Heureux for his cash, and that Harakles was abusive to her father. L’Heureux did loan Harakles $40,000, but she repaid it, according to court documents. The judge, however, said other withdrawals from L’Heureux’s accounts likely ended up with Harakles, although she denies it.

All the while, L’Heureux repeated his desire to marry Harakles and have her care for him.

In a March 2014 decision, York County Probate Judge Robert M.A. Nadeau found that, despite L’Heureux’s “somewhat heart-wrenching pleas,” it was “simply too unsafe for him to continue living alone, and too burdensome and unfeasible to expect his children to check up on him as much as had become necessary.”

Harakles, the court found, would be of no help caring for L’Heureux and, in general, was a source of disruption for Carroll in her plan to care for her father. In some cases, the court said, she was controlling and possessive of L’Heureux.

“Real’s notion that Grace can adequately and properly take care of him has been and remains unrealistic,” Nadeau wrote.

Although Harakles was allowed to visit with L’Heureux and take him on excursions after he was placed at Lodges Care Center in Springvale, the court found that Harakles quickly abused the privilege, and it limited her to visits inside the facility.

The tension between Harakles and Carroll escalated in May 2014, when Carroll filed a protection-from-harassment order against Harakles. But a judge threw out the case after L’Heureux showed up in court to testify that there was no harassment, and that he and Harakles were in a mutual, loving relationship.

Their relationship continued, albeit during visiting hours, until a few weeks ago, when Carroll moved L’Heureux to a dementia ward at the Pavilion.

After five years of almost daily visits, the couple had no contact for a week.

Then, before noon on Tuesday, Harakles’ phone rang, and they were reunited.

Harakles resents the notion that she is unfit to care for her boyfriend, and resists the notion that he has cognitive impairments.

To her, L’Heureux is “all there,” she said.

Though he is articulate and appeared lucid and sharp during the interview, he also clearly has memory gaps, such as the name of the second of his three wives.

Their relationship is not about money, she said, but love.

However many years L’Heureux has left, “they should be happy years,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.