The Portland Museum of Art biennial that opens Thursday will look and feel very different from any of the seven previous biennials hosted by the museum since 1998.

Previously, the biennials have served as surveys of contemporary art in Maine, a snapshot, if you will, of the evolving art scene at a given time.

The “2013 Portland Museum of Art Biennial: Piece Work” is not that.

This biennial is built around a theme of labor, repetition and production. This isn’t factory work that we’re trying to appreciate here, but it comes from same ethic of getting up in the morning, going to work and coming away with something tangible to show for your day’s efforts.

These are not shoes that we are stitching, or paper that we are making, but the 70-plus pieces of work produced by 30 artists very much fit into Maine’s centuries-old tradition of handiwork, skill and pride.

These are beautifully articulated paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures and videos, conceived, tested and perfected by artists who represent not just the best of Maine’s contemporary art scene, but the very core of Maine’s cultural tradition that involves working with one’s hands, using inherent and learned skills to create objects of awe and wonder.

“I think what this exhibition speaks to is the idea of doing work again and again, and the idea of doing something with your hands,” said Jessica May, the museum’s curator of contemporary and modern art. “There is something about the tradition of handiwork that kept presenting itself.”

The 2013 biennial is different in another way. For the first time since it began in 1998, the artists and art work in the biennial were not chosen by jury. May made the selections herself — based first on images submitted by the artists, and later, she narrowed her choices based on studio visits with nearly every artist selected.

That process results in a very different kind of biennial. The juried process often results in a net cast wide, one big enough to grab the likes and interests of a three-member jury panel. Those shows were widely varied, with art work that covered a broad range of disciplines, visions and degrees of articulation. In every sense, those shows truly were a snapshot — perhaps better described as a grab bag.

This biennial represents a single, curated view.

May has been on the job since June 2012, and began thinking about the biennial as early last fall. It presented a perfect opportunity to immerse herself deeply into the Maine art scene, to get to know not just the artists, but the kind of work that artists from Maine like to make.

The first thing she learned is that artists from Maine are not all that different from artists from away. The gap between a Maine artist and an artist from anywhere else “goes away very fast. Artists from Maine are thinking broadly. That sense of what it is to be from Maine is a lot more complicated than I thought it would be,” she said.

Which is to say, “I think the work in this biennial is as good as the work in any biennial in the United States are anywhere else. The level of professionalism among artists here is very high.”

Each artist in this exhibition has deep Maine connections. Many live here year-round. Some are part-time Maine residents. Others went to school here. For a few, Maine plays an important role in their artistic practice.

But the connection among all of them is their commitment to the notion of a producing body of work, of endlessly repeating a pattern or habit to produce one thing after another. Hence, the subtitle of the show, “Piece Work.” If nothing else, this is an exhibition about labor and the art of making.

We see evidence of that theme at the outset. May has wrapped a portion of the Great Hall with a vinyl wallpaper produced by Adriane Herman and Brian Reeves, both Portland-based artists. For a decade, Herman has been thinking about to-do lists. She has collected to-do lists from family, friends and neighbors, manipulated them digitally and transferred them into a wall installation that takes the form of wallpaper.

The idea of repetition presents itself not just in the individual to-do lists themselves, which represent reminders about what we must accomplish, day in and day out, but in the repeating pattern of the wallpaper. It’s a pleasant visual experience, transforming the Great Hall from a place of high art into one of daily domesticity, with scribbles that say, “Call your mom,” “Drop Class,” “Heart worm pill” and most optimistically, “Plan weekend.”

Inside the first-floor galleries, visitors are treated to an array of work, some that hangs on the walls and other displayed on the floor. The first large-scale installation is “Ha-ha,” a mixed-media piece by another Portland artist, Lauren Fensterstock.

For “Ha-ha,” Fensterstock has employed her familiar flower petals and blades of grass, all made with black paper, and assembled them in 10-by-10-foot wooden box that stands about 4 feet tall. It takes its name from an English landscape feature. Instead of a fence, 18th-century English landowners would cut a ravine into the earth to create a boundary for their livestock. A fence, they felt, would hamper their view of the landscape, while the ravine, or ha-ha, created the illusion of an untouched landscape.

Kate Beck’s “Modern Structure” is an ode to discipline. Beck, who lives in Harpswell, created 100 graphite-on-paper drawings, each 10 by 10 inches and mounted on wood. Her palette is mostly black and white, and her form is a long, straight line, repeated over and over again to create what the artist describes as “quiet blocks of subtle gradients evolved from deliberate, repeated lines.” Hung on the wall, the 100 drawings create a stunning visual effect.

JT Bullitt, based in Steuben, is a seismologist by training, an artist by choice. Among his pieces in this show are a series of continuous drawings, some of which look something like a seismologic graph. The concept of a continuous drawing is not unique, but Bullitt does his with a flair that is both memorable and somewhat funny. One, titled “I Will Not Stop Until I am Asleep,” meanders back and forth down the 9-inch paper page until the line just stops, in mid-sentence as it were. That, apparently, is where Bullitt rested his eyes.

He has several other pieces in the show, including an audio installation called “Who I Am (Everyone I Have Ever Known.” It involves a two-hour iPod recording of Bullitt speaking the first and last names of every person he has ever known or whose name he could remember. It’s kind of like him reading the phone book, only randomly. Obsessive, curious and utterly compelling — at least for a minute or two.

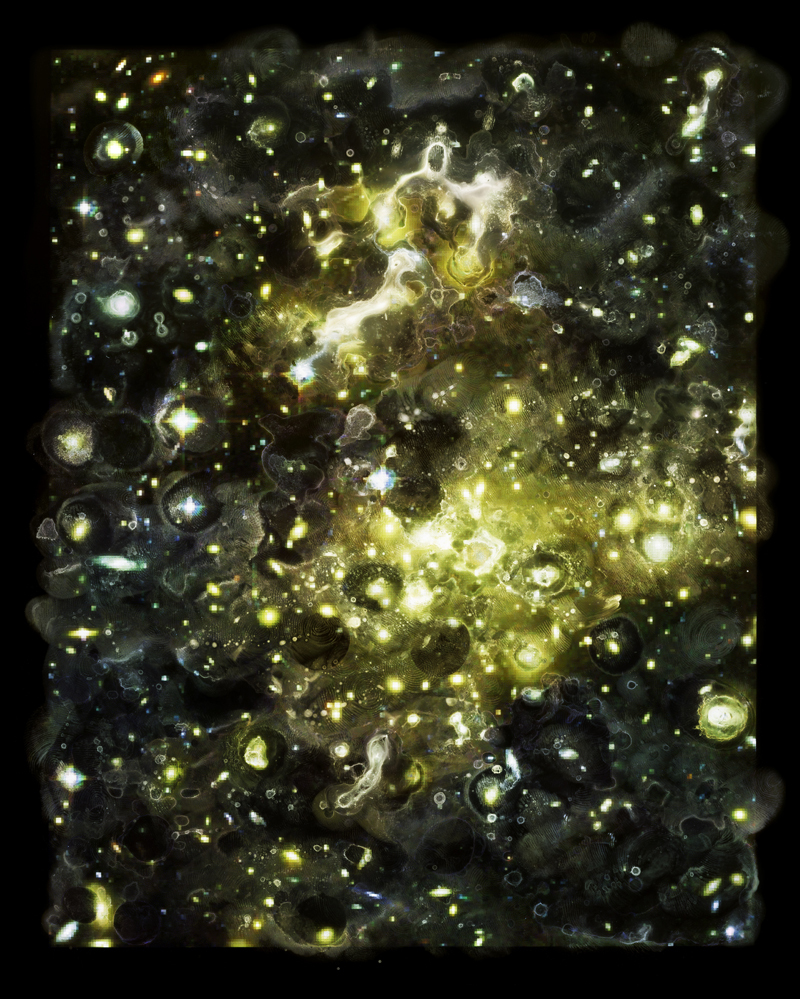

Down the way, we encounter a series of inkjet prints from Waterville-based photographer Gary Green. In his series “Terrain Vague,” he documents the abandoned landscapes of industrial central Maine. The photos show evidence of past human activity, but are devoid of much of anything beautiful anymore. These are where the strip malls, subdivisions and industrial parks of the 1970s used to be. Now, there are just abandoned lands, with power lines and rutted tire tracks passing through.

Around the corner is the wall-sized installation called “Library,” by Appleton artist Abbie Read. She evokes a folk-art aesthetic, assembling a patchwork of old books, handmade books, book covers and found objects. It’s among the more colorful pieces in the show, and raises questions about nostalgia, collecting and the role of relics in our lives.

There are many examples of similarly obsessive works — Portland artist Joe Kievitt’s unrelenting geometric drawings, one of which has 1.5 million individually drawn lines; Duane Paluska’s minimal sculptures; or Julie Gray’s plastic beaded wall-based works that look like textiles.

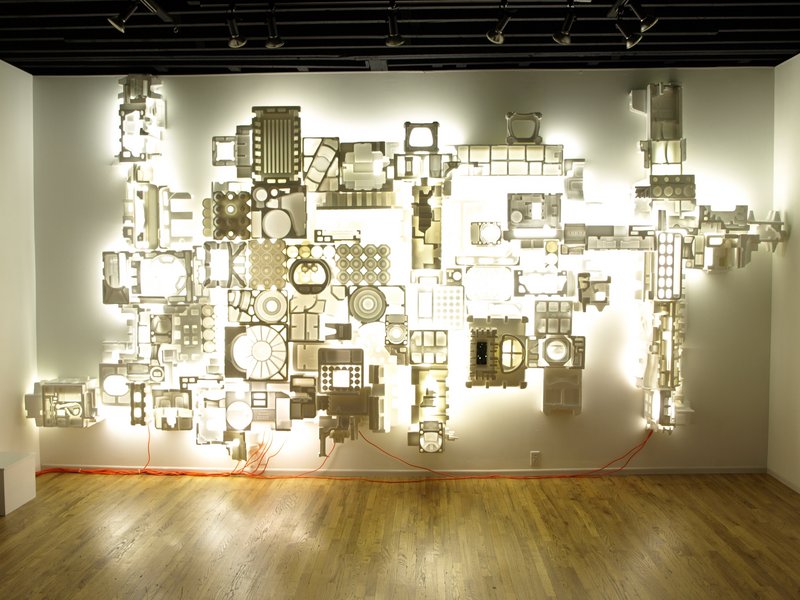

May has arranged for biennial pieces throughout the museum, including two installations in the McLellan House. One of the installations is from Georgetown artist Jason Rogenes, who has converted the Family Space in the McLellan House into a room of cardboard and poly foam.

Sound artists Zaff Poff and N.B. Aldrich have rigged “Bell Cloud” in the parlor of the McLellan House. It uses atmospheric energy to create sounds from bells that are suspended from the ceiling. The little bells probably are similar to the kind of bells used to summon hired help back in the 19th century, when the McLellan House was built. In that sense, this piece evokes the past while looking squarely into the future.

Alongside the McLellan House’s flying staircase, Rangeley artist Justin Richel has installed one of his whimsically drawn towers of stacked goods, this one featuring the accoutrements of the bourgeois — a stuffed chair, human bust, ornate vase, tea pot and confected dessert.

May knows well that viewers will have a range of reactions to this work. Above all, she hopes they appreciate the creative efforts of the artists.

“Photography, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and textiles seems to cross historic boundaries fluidly,” she writes in the curator’s essay. “These are not dystopian or regressive gestures; instead, the art of ‘Piece Work’ suggests a shared investment in the value of hands and fingertips, along with an investment in time that refuses the logic of efficiency and speed.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be reached at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 5:20 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 4 to correct the spelling of J.T. Bullitt’s name.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.