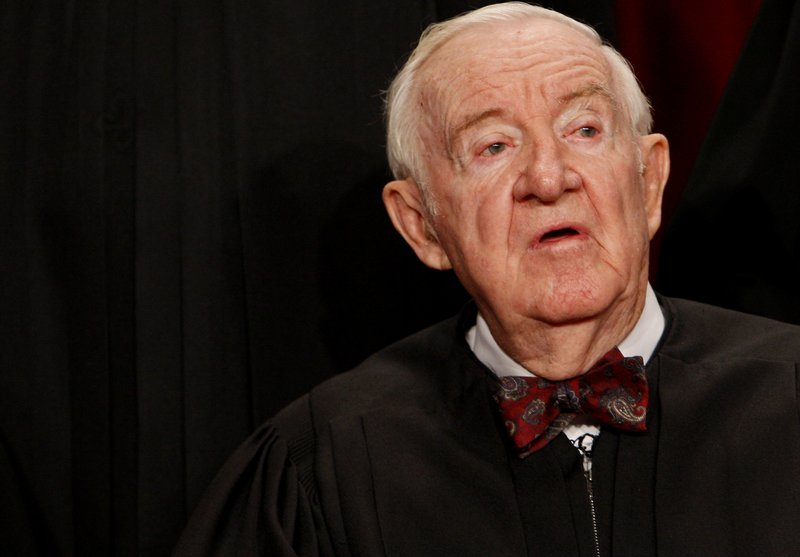

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court career of John Paul Stevens could not have been easily predicted in 1975, when he arrived as a Midwestern Republican with a background in corporate and anti-trust law.

A World War II vet, he wanted no part of defending pornography as a free speech issue. “Few of us would march our sons and daughters off to war to preserve the citizen’s right to see sexually explicit ‘adult’ movies,” he wrote in his first major opinion. Having replaced liberal Justice William O. Douglas, Stevens also cast a key vote in his first year to restore the death penalty after a four-year ban.

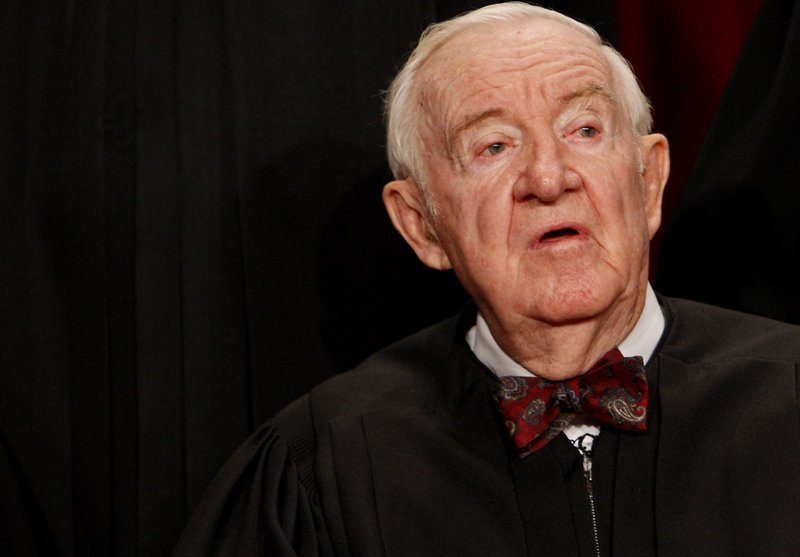

But since the mid-1990s, Stevens has been the leader of the court’s liberal wing and its strongest voice for progressive causes. He supported a strict separation of church and state and vigorous enforcement of laws to protect civil rights and the environment.

He championed clear limits on the “influence of big money” in American politics. “Money is not speech,” he said, but property subject to regulation. And two years ago, he called for an end to “state-sanctioned killing,” insisting the “real risk of error” made the death penalty no longer acceptable.

So what changed? Did Stevens become more liberal over three decades, or did Stevens hold to the center while the high court shifted right in response to appointments by Republican Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush?

As Stevens saw it, he held to the center. On abortion, prayer in schools and campaign spending, he tried to maintain the law as it was when he joined the court. For example, he voted to uphold state laws that required young girls to have their parents consent to get an abortion. But when Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia pressed to overturn the right to abortion entirely, Stevens became a steady defender of Roe v. Wade, the decision that established that right.

When Rehnquist and Scalia favored a more public role for religion, Stevens stood for a strict separation of church and state, opposing moves to permit prayers in public schools or public aid for parochial schools.

In January’s ruling giving corporations a free-speech right to spend unlimited sums on elections, Stevens dissented, defending the long-standing power of Congress to restrict corporate and union money in campaigns. In these and other votes; his “liberal” stands amounted to defending the status quo.

President Gerald Ford chose Stevens because of his reputation as a highly capable and nonpartisan judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals in Chicago. And in his early years, he fit the profile of an independent-minded, middle-of-the-roader. He was often described as unpredictable and even quirky.

But as the court shifted toward the right in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Stevens appeared to shift left. default, he became the senior voice on the liberal side after the court’s most prominent liberals — Justices William J. Brennan, Thurgood Marshall and Harry Blackmun — retired between 1990 and 1994.

There is also ample evidence that Stevens changed his views on several major issues. Affirmative action is a prime example. In the famous 1978 Bakke reverse-discrimination case, he joined the conservatives who said the University of California had violated the rights of Allan Bakke, a highly qualified white applicant to the medical school. In one opinion, he compared laws that set aside contracts for certain racial minorities as reminiscent of the Nazi-era laws.

While he remained uncomfortable with “affirmative” preferences, he later moderated his position, saying he believed the court should defer to lawmakers, employers or universities that wanted to give a limited benefit to minority applicants if the goal was to foster equality.

He also shifted away from the death penalty over time. In 1987, he agreed with a dissent by the liberals saying that racial discrimination played a troubling role in the administration of the death penalty. In the past decade, he led a move within the court to limit its use. Working closely with moderate Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, Stevens and the court abolished the death penalty for defendants who were mentally retarded or were under age 18 at the time of their crimes. As Stevens saw it, a “national consensus” had formed that these murderers, while deserving to be kept in prison, did not belong among the small number of offenders who should die for their crimes.

In recent years, the court clashed with President George W. Bush over the treatment of military detainees at Guantanamo Bay, and Stevens led the move to give these prisoners a right to a hearing before a judge.

Stevens had served as an intelligence officer in the Pacific during World War II and was a young clerk at the high court after the war when several Japanese generals were executed for brutalities committed by their troops. Like his boss, Justice Wiley Rutledge, Stevens believed these military trials followed by quick executions reflected badly on the American system of justice.

In the Guantanamo cases, he rejected the notion that the president, as commander in chief, had sole control over how the prisoners in the “war on terror” were to be held and tried. He also insisted that the Geneva Convention and its requirement of humane treatment extended to Guantanamo, since the prisoners there had been captured in an armed conflict.

Stevens’ early life had more than its share of grand moments and deep tragedies. He was born in 1920, the fourth of four boys in a wealthy family. He was 7 when his father opened the 28-story Stevens Hotel on Michigan Avenue (now the Hilton Chicago), overlooking the lake.

It was said to be the largest hotel in the world, and the young boy met the traveling celebrities of the era, including aviators Charles Lindbergh, who gave young John a dove, and Amelia Earhart, who advised him he should be in bed because it was a school night. A fan of the hometown Cubs, he watched at Wrigley Field as Babe Ruth pointed his bat at the outfield bleachers and hit the next pitch there during the 1932 World Series.

But by then, his family’s prospects had darkened with the Great Depression. The stock market had crashed two years after the Stevens Hotel had opened, and the business collapse that followed drove the hotel into bankruptcy. Stevens’ father, uncle and grandfather were accused of having embezzled more than $1 million from the family-run life insurance company to prop up the failing hotel. His grandfather suffered a stroke, and his uncle committed suicide. Left to stand trial alone, his father was convicted. A year later, however, the Illinois Supreme Court unanimously overturned the conviction and said that transferring money from one family business to another was not embezzlement.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.