TOWNSHIP 1, RANGE 8 – A 50-seat restaurant is rising in the woods near the shores of Millinocket Lake, part of a long-term vision for a new economy in the Katahdin Region.

Matt Polstein climbed a ladder to the second floor last week and took in the view.

Gazing across the frozen lake at the iconic summit of Mount Katahdin, he talked about the potential for nature-based tourism and the latest, controversial proposal for a national park.

“A lot of people have no sense of what an economic engine a park could be,” said Polstein, who’s building the $650,000 restaurant as part of his New England Outdoors Center complex at Twin Pine Camps. “They focus on the risks, not the gains.”

As he spoke, selectmen in nearby East Millinocket were huddled in the town office in a desperate struggle to save the remnants of the old economy.

East Millinocket calls itself “the town that paper made.” But now a man-made icon, the century-old paper mill that dominates the local landscape, has shut down, taking with it the region’s last papermaking jobs and its heritage.

No national park can offset the loss of a manufacturing economy, some residents insist. A federally run park could remove land from taxation, limit timber harvesting and end traditional uses such as hunting, they say.

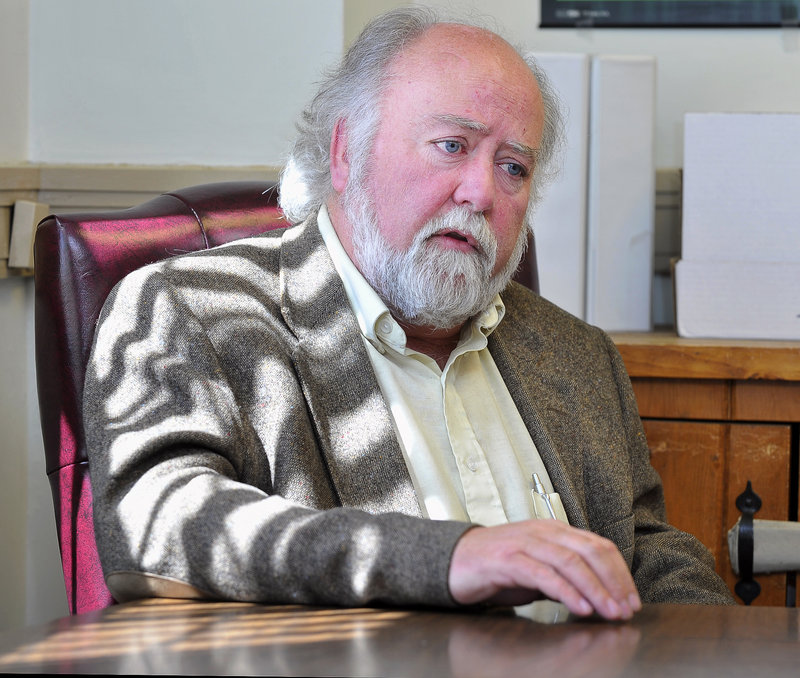

“I embrace tourism,” said Mark Marston, a selectman who worked in a now-closed paper mill in neighboring Millinocket for 20 years. “But a national park, no, there are too many negatives for me.”

Debate here over a national park has ebbed and flowed for years. But now the convergence of two events — the shutdown of the Katahdin Paper Co. mill and a revived proposal for a 70,000-acre national park — is bringing a difficult question into sharp focus: In a region built on making paper, what happens after papermaking goes away?

That question could be decided in the next five days. Friday is the deadline that Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management, the parent company of Katahdin Paper, has given for finding a new buyer. The company has threatened to start dismantling the mill after that.

A San Francisco-based company that had expressed interest in the mills backed out of negotiations two weeks ago.

THRIVING INDUSTRY SHRINKS

Arriving at this point in history still seems unthinkable.

Millinocket was incorporated in 1901. It was nicknamed “The Magic City,” springing up in the North Woods around the Great Northern Paper Co. mill and what were then the world’s largest paper machines. A sister mill was built down the West Branch of the Penobscot River in East Millinocket.

Papermaking created thousands of good-paying jobs and pushed Millinocket’s population to nearly 10,000. But global competition and changing technologies slowly eroded the mills’ advantages. Great Northern Paper filed for bankruptcy in 2003. The Millinocket mill restarted, but closed again and has been idle since 2008.

No paper, no jobs. The East Millinocket mill employed the last 450 papermakers when the machines stopped on April 1.

With the jobs went the people. Millinocket’s population has fallen by half over the past decade.

Millinocket’s unemployment rate hit 17 percent in February, and that was before the mill closure. Downtown, vacant buildings put a sad face on Penobscot Street, once the center of commerce. Stearns High School, which had 700 students in its heyday, is down to 200. The superintendent went to China last year to recruit Chinese students, who will pay enough in tuition to help keep the doors open.

Clearly, The Magic City needs some new tricks.

A SCALED-DOWN PARK PLAN

One idea is a Maine Woods National Park in remote forestland north of Millinocket, adjacent to Baxter State Park and Mount Katahdin. This is a scaled-down version of a 3.2 million-acre concept that has gained little traction over many years. A 70,000-acre park is being promoted by Roxanne Quimby, the wealthy conservationist who has been buying property in the region for years and wants to donate her land to the National Park Service.

Parks can attract money to rural regions. A study done three years ago for Baxter State Park estimated $6.9 million in economic activity, with the average visitor spending $187 in the community and $198 elsewhere in Maine.

Maine’s North Woods already offer many recreational opportunities. But a national park creates a globally recognized brand, according to Polstein. Brand identity is important in tourism, as a way to market a destination.

A national park could help Polstein realize his dream of creating “Ktaadn Resorts,” a mixed-use development with a hotel, conference center and artist village. The $65 million project has won state zoning approval, but so far lacks investors and development partners.

In the meantime, Polstein has spent $2 million to build six luxurious cabins on a cove next to Twin Pine Camps. They rent for $500 a night. The cabins complement his bigger plan for a destination resort with good food, services and amenities to keep hikers and whitewater rafters around for a few days, and spending money.

“The stay is part of your vacation,” he said. “This is a setting that makes you want to relax and do other things.”

One of those things might be wildlife photography.

Mark Picard and his partner, Anita Mueller, were washing clothes last year in a downtown laundromat when they noticed a house for sale. They bought it, moved from western Massachusetts and opened a photo gallery and wildlife photography business.

Their gallery, Moose Prints, is on the well-traveled road to Baxter State Park. Picard, who has been capturing images of moose for 30 years in the Katahdin region, now leads field workshops that draw participants from as far away as New Zealand. The price is $850, with lodging at a local inn.

“If the mills are done, other things will have to take their place,” Picard said. “But it’s going to be hard for people to wrap their brains around that.”

Moose Prints shares a tiny, downtown art scene with North Light Gallery, which showcases local artists, and Memories of Maine Gallery. The most novel tourist attraction is the Pelletier Loggers Family Restaurant, part of a $1 million renovation that serves hearty meals and showcases the logo gear available for the Discovery Channel’s “American Loggers” reality show.

It’s unusual to hear someone talk about the “creative economy” around here, but Mark Scally, a former music teacher who chairs the East Millinocket selectmen, says these businesses hint at what’s possible.

“There is a creative economy we can latch on to,” he said. “But a lot of people around here don’t want to embrace that. They still believe we can only make paper.”

Scally stresses that his first priority is to keep the mill operating, or at least intact for a future owner. But he also sees a future in which the Katahdin Region can be a smaller version of North Conway, N.H., with a four-season, tourism economy growing up around well-promoted natural resources.

To encourage diversification, Millinocket, East Millinocket and Medway are using an annual compensation payment from the closed Millinocket mill to fund the Katahdin Area Recovery & Expansion Committee. The committee gave $18,000 to a local snowmobile club, for instance, to build a drag-racing track in Medway that can draw hundreds of racers and spectators.

Money also has gone to help open the Soup to Nuts restaurant in East Millinocket, owned by two experienced caterers who came years ago to hike in Baxter State Park and wanted to live here.

“The only way this area is going to lift itself up is through the people,” Scally said. “We need to stop waiting for a white knight. We need to be the white knight.”

Marston, the retired paperworker and selectman, agrees that redevelopment must be driven by local visions. A national park, he says, would take away that local control.

“We can redevelop ourselves,” he said. “We don’t need someone else coming here to tell us. We’re already open for tourism. But we’re also open for paper.”

TRADITION, TOURISM OR BOTH?

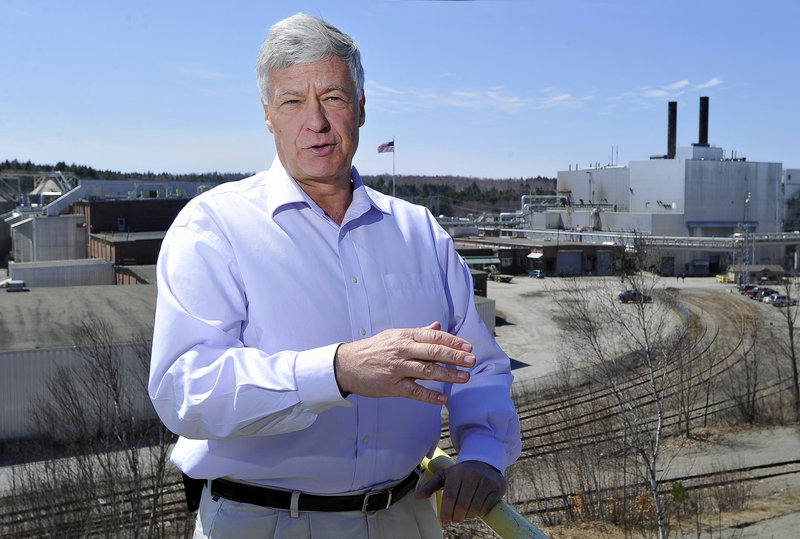

Open for tourism and open for paper. That’s the best-of-both-worlds goal for U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud, D-Maine. Michaud has a unique perspective on the debate. He grew up in East Millinocket and worked in the mill for 29 years before being elected to Congress in 2002.

Congress would have to approve any new national park, and Michaud has mixed feelings. He’s opposed to any park that would limit snowmobiling, hunting or timber harvesting. But he’s willing to learn more about the details of Quimby’s proposal and understand how it would impact traditional uses.

Michaud was in town last week during the congressional recess. He has been working with officials here, and in Augusta and Washington, D.C., in a last-ditch bid to keep papermaking alive in the Katahdin region. That’s part of his job, of course, but like most residents who have grown up in papermaking and earned a living from it, manufacturing is in Michaud’s DNA, and he personally cannot let it go without a fight.

Standing on an overlook above the empty mill yard last week, Michaud reflected on the dilemma facing his hometown.

“People realize it’s not going to be the way it was,” he said of the industry. “But by the same token, my hope is this mill will still be making paper.”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.