LAC-MEGANTIC, Quebec — Motorists here still stop at the railroad tracks and look both ways.

Such are the habits of people living in a town built around a transcontinental railway.

But nobody has seen or heard a freight train since the riderless “ghost train” hauling crude oil rolled into town on July 6 and exploded, killing 47 people and destroying 40 buildings downtown.

The rail line has been blocked while crews work to clean up 1.5 million gallons of spilled oil and remove debris.

While trains could be allowed to pass through within a few months, the long-term prospects for rail here are uncertain.

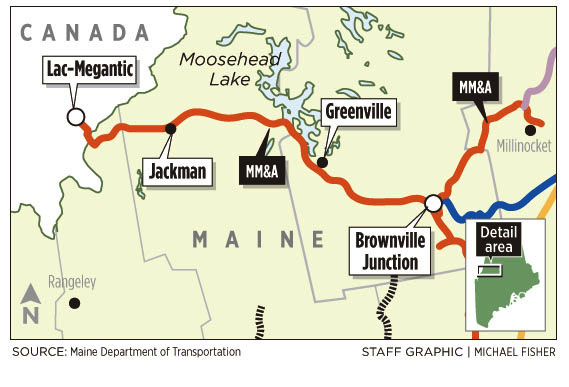

What happens in Lac-Megantic has ramifications in Maine, where the rail line is a link between Maine lumber and paper mills and their customers throughout North America.

At issue is not the survival of the line’s bankrupt owner, Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway, which is looking for a buyer, but whether the line can be run as a sustainable business under any owner, given its scattered customer base, high fixed costs and daunting political obstacles.

Because of the decline of Maine paper mills over the past decade, the railroad had been struggling financially. Only in the past year and a half, after it began hauling crude oil for the Irving oil refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick, did the railroad make enough money to begin upgrading its deteriorating infrastructure, according to the railroad’s chairman, Ed Burkhardt.

The railroad had been hauling 500,000 barrels of oil a month until the accident.

That business is now gone.

FIERCE OPPOSITION

Despite Lac-Megantic’s economic dependence on rail, any attempt to bring oil tankers through downtown will be met with fierce opposition here.

The public will simply never allow it, said Yannick Thibault, 44, head coach of the football team at Lac-Megantic’s high school.

While visiting the “red zone,” the epicenter of the crash, Thibault said that four former players were killed. He said the area is a cemetery because five bodies have never been found.

He said people in Lac-Megantic are afraid of another train accident and will do everything they can to protect their town.

“You can’t hurt our city twice,” he said.

Half of the downtown was destroyed in the blasts. After the cleanup is complete, a process still months away, the town will allow only “safe” cargo — such as lumber, logs and consumer goods — bound for the port of Saint John to travel on existing rails.

Meanwhile, officials and business leaders have begun talking about re-routing the line so it goes around the town. But it would take a couple of years to plan and build the new nine-mile line, and nobody has figured out how to pay for it.

MAINE SAWMILL AFFECTED

It’s questionable whether there’s enough business to sustain a rail line that has relatively few customers while passing through a remote and mountainous region, say some experts in the rail industry.

Between Lac-Megantic and Brownville Junction in Maine, a stretch of 117 miles, there is only one customer, Moose River Lumber, in the town of Moose River near Jackman.

Until the accident last month, the railroad every week had been operating three trains made up of oil tank cars bound for Saint John, according to Steve Banahan, sales and transportation manager for Moose River Lumber.

In addition, the railroad each week was running three eastbound freight trains and two westbound trains, he said.

On July 6, Banahan was able to smell the smoke rising from Lac-Megantic 30 miles away. He said he knew immediately that his sawmill would be hit financially by the disaster.

The sawmill relies on the railroad to ship lumber to Montreal and then south and west. With the route through Lac-Megantic now blocked, the sawmill is using a roundabout train route through southern Maine and Massachusetts. The greater distance adds an additional $500 to $1,500 per car, pricing Banahan out of markets beyond Baltimore.

The region’s heavy snowfall requires special trips by locomotives equipped with plows to clear the tracks. There are several old trestles to maintain, including a 1,200-foot-long trestle that crosses a river gorge near Greenville.

“It’s a hard place for railroads,” said Don Marson, who retired in June from his job as vice president and general manager of the Maine Eastern Railroad.

Marson said it’s difficult to make money on a railroad with far-flung customers because the per-mile maintenance costs are the same for all railroads, no matter how many customers are on the line.

To lower operating costs, Burkhardt introduced one-man crews. But that practice is now off-limits, banned by the Canadian government in response to the accident last month.

Because of work schedules, the ban effectively would require two-man crews in Maine as well, from the Quebec border to Brownville Junction, making the odds of the line’s survival “even bleaker,” Marson said.

Another political issue is whether the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway has enough insurance to satisfy the Canadian Tranportation Agency.

The agency earlier this month said it would halt the railroad’s operations on Aug. 20 but said Friday it will give the railraod until Oct. 1 to provide new evidence about its insurance.

Maine taxpayers could come to the rescue, at least for the Maine portion of the line. The state could buy the line and make a deal with another railroad to operate trains on it.

While discussing the importance of approving a transportation bond, Maine Transportation Commissioner David Bernhardt last week said he needs money to make that option available if the railroad gets broken up and some of its routes are abandoned.

“We need that east-west connection,” he said during an interview on a Portland radio talk show.

That’s what happened in 2010, when the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic said it planned to abandon 233 miles of rail in the northern part of Maine. The state bought the line for $20.1 million to keep the trains running under a different operator.

The move saved 2,200 jobs in mills dependent on rail transportation, state officials said.

Many of those mills use the line between Brownville Junction and Lac-Megantic as a direct east-west route to railroads that span the continent.

If the line to Lac-Megantic becomes abandoned, the Moose River sawmill would be stranded without rail service. Noting that the state purchased the northern segment of the former Bangor and Aroostook Railroad line to save jobs, Banahan said the state may need to buy this line, too.

“If that northern line is a critical piece, this is more so,” he said. “This is the main artery.”

IMPACT ON LAC-MEGANTIC FACTORY

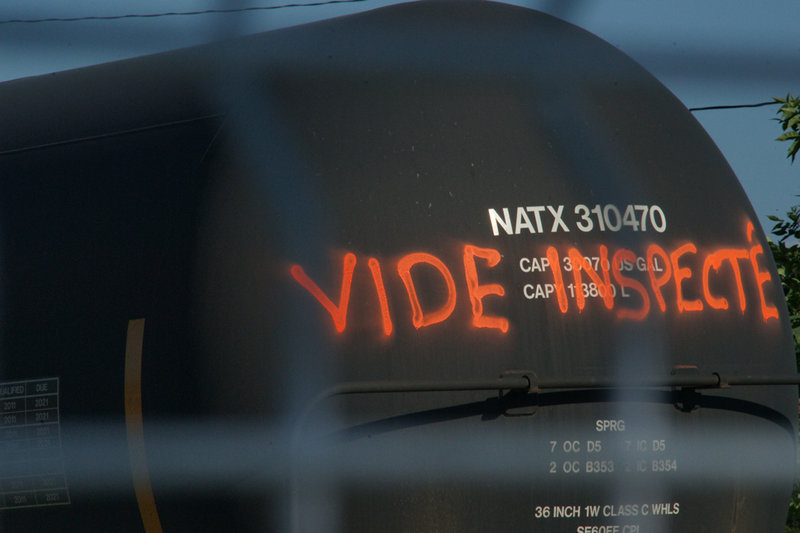

Today the route is severed at Lac-Megantic. Empty boxcars sit on a rail spur outside the massive Tafisa factory that dominates the town’s skyline. The cars haven’t moved since the disaster early last month.

The factory, the largest producer of particleboard in North America, is the town’s largest employer, with about 350 workers. The factory normally uses rail to ship products to 35 percent of its customers. It uses a rail spur that begins at the factory and intersects with the mainline at the red zone.

Twelve nearby sawmills also use the spur for shipping products and receiving raw materials by rail.

Those companies are now using trucks, a more expensive option for long-distance delivery. Tafisa is now trucking products to three reloading centers on other railroads, all within three hours’ drive, said Louis Brassard, the company’s CEO.

While Tafisa will be able to cope with the rail shutdown in Lac-Megantic for the next few months, it needs direct rail service to be competitive, he said.

He said Lac-Megantic residents will need to accept the idea of freight trains moving through town again.

“We will need to restore the tracks,” Brassard said. “Eventually, we will need to have rail.”

Many people don’t understand how important the rail line is for the local economy, said Francis Cliche, a scrap dealer in Frontenac, a town adacent to Lac-Megantic. Before the accident, his business had been using the railroad to ship scrap to a buyer in Massachusets. Now the yard is busy scrapping 3,000 tons of metal taken from the railroad’s busted tank cars, which were strewn all over downtown Lac-Megantic.

Still, as much as he wants the rail line restored, he understands why people no longer trust the railroad. His children’s baby sitter was killed in the disaster.

“Everybody lost somebody,” he said.

Felix Provost, 36, who owns a hotel outside of Lac-Megantic, grew up near the railroad tracks and remembers the frequent trains that rumbled by his house. He used to love watching the trains, he said, but he has lost faith in their ability to move dangerous cargo safely.

The town is now overwhelmed with tasks, such as building a new downtown for the 125 displaced businesses, he said.

At a forum he attended last week with government officials, residents and business owners about the future of the town, it was clear that restoring rail service is a low priority for most people, he said.

“It’s at the bottom of the list.”

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Twitter: TomBellPortland

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.