When I recently walked into Ed Pollack Fine Arts to see the David Itchkawich show, I was struck by a pair of fine drawings by Ken Greenleaf.

While I think his new paintings are very strong, I prefer his drawings. Seemingly simple, their visual and intellectual gymnastics flow and swoop gracefully by means of a surprisingly flexible muscularity.

Greenleaf’s wife, Dozier Bell, now has a show at Aucocisco. Superficially, their work could hardly be more different. Bell’s works are painterly scenes with realistic textures and details as opposed to Greenleaf’s linear abstractions. What they share, however, is a basis in Romantic philosophy.

Previously, Bell’s paintings addressed remote-sensing technologies — radar, bomb sites, etc. — often tied to a nostalgic World War II aesthetic. I’ll never forget a tiny charcoal-on-mylar view of a ship through a submarine’s targeting periscope. The scene is tilted like a torpedo incident, but the ship is actually flat on the water, while it is the periscope that is tilted. It might be subtle, but you know something is seriously wrong — and that’s the point.

Bell’s atmospheric density and dreamy feel places much of her work squarely in the shadow of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the great Romantic painter of melancholically dreamy and powerfully spiritual landscapes. Bell’s “Burg” images practically glow with the ghostly mystery of magical ages past.

However, Bell’s newer paintings achieve something more penetrating by employing a touch of technology. The electronic crosshairs of “Oculus 5,” for example, invert a would-be mystical sky from simple landscape painting into contemporary meditation on the semiotics of an aerial battlefield.

The effect is unusual insofar as it presses the Romantic conception of perception. As opposed to the transferable scientific objectivity of the Enlightenment, Romanticism prioritizes personal insight.

One of my favorite works in Bell’s show is “Smoking,” a hazy view of a fire below the surface of the ocean. While I read this immediately as a destroyed submarine, the mystery of the narrative is the primary effect. The metaphor of impenetrable depths, violence and unknowable mysteries is exquisitely sublime.

A newer piece, “Flock,” pressed me to a more expansive understanding of Bell’s images as conjectural (hunter/detective) knowledge. We don’t see it directly, but the downward funnel of carrion birds is a clear trace of the grim quarry.

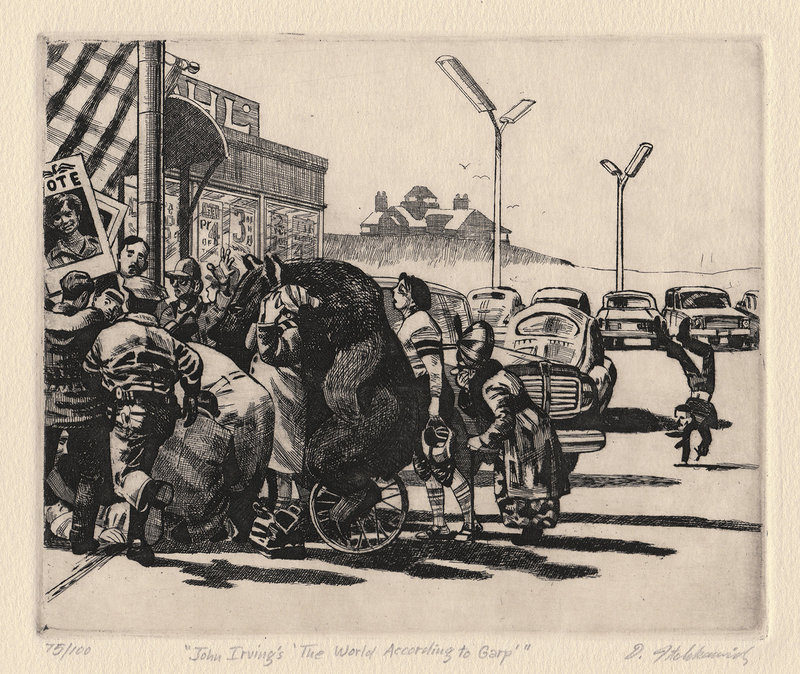

Itchkawich’s etchings at Ed Pollack also ride a Romantic approach. While a few of the artist’s prints are straightforward illustrations — such as his “John Irving’s ‘The World According to Garp’” done for the New York Review of Books — most are fantastical scenes from the artist’s imagination.

Itchkawich’s repeated returns to World War II and 19th-century style bring the content of his work into a fascinating dialogue with Bell’s. While Itchkawich’s are dedicated to mysterious narrative flow and Bell’s feel more experientially meditative, they both combine data with pictorial aesthetics in a way that clearly prioritizes subconscious responses in the viewer. In other words, they value sensibility over sense.

Itchkawich’s “Concert at the Night Encampment” appears to feature a group of 19th-century explorers watching a performance off to the right of our field of vision. Yet behind them — strongly balancing the composition of the image — is a pair of penguins that places us in Antarctica.

Maybe fixation on their portable culture appears to be the reason these explorers don’t notice the indigenous inhabitants. The dream logic is ramped up by the striking white; maybe the “night encampment” itself is a reference to our dreams.

Another of Itchkawich’s odd images that also plays to the remote-sensing technologies of Bell’s work is “Serpents in the Meeting House.” The scene shows a very early recording session in which a strangely straight horn is focused on a quartet: piano, cello and two bizarrely serpentine horns. The meetinghouse already has a double life implied by the hymnals in the pews.

These remind us this is a place of public music, and that we are witnessing a private performance with the intention of public consumption by means of technology. It’s the standard logic of recording, but its oddness echoes through the scene (and the ages). It’s also a metaphorical reminder that the artist’s work intended for public consumption is usually made in private and filled with personal thoughts.

I think Bell’s and Itchkawich’s Romanticism is brilliantly on target, because we’re at a tipping point of the age-old battleground of renaissance and baroque. Contemporary art of the moment is being tossed on a sea of sense and sensibility. And they get that perfectly.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.