Trompe l’oeil is a fancy but useful art term for illusionistic painting.

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel comes to mind, but there are several accessible examples around Portland, including the building-sized “Blueprint” at 40 Free St., in which a life-sized architectural drawing appears superimposed on a real building. The humor of the piece is underscored by how the “edge” of the drawing rolls back to reveal the actual building. Well, almost: the revealed window is an illusion as well.

On the heels of the 19th-century diorama sensation, trompe l’oeil (literally, “fool the eye”) enjoyed a heyday in American popular culture. The most famous practitioner was William Harnett (1848-92), whose paintings convincingly depicted quotidian objects such as pipes, books and musical instruments.

The illusion was achieved by solid painterly techniques such as modeling and convincing shadows, but it relied just as heavily on subtle devices to aid spatial legibility: a book extending over the edge of a table, spilled pipe ashes, frayed edges or paper curling up and so on. Adding nothing to the narrative, they are simply vehicles for illusionistic detail.

In addition to Harnett, the other American painters most noted for this style were John Peto (1854-1907) and John Haberle (1856-1933). Works by all three are in “John Haberle: American Master of Illusion” at the Portland Museum of Art.

Seeing their work together is extremely revealing. Harnett — the most famous and influential of the trio (Cubism in particular owes him a specific debt) — is more old-school, and seems a bit loath to hide his handsome brush strokes. Peto’s brush work and illusion are the weakest, but his sense of metaphor is the richest and most thoughtful.

Haberle is the least celebrated, the wackiest (just look at his “That’s Me!”) and in many ways the most impressive. His illusion can be astonishing, while his wit is ever effervescent.

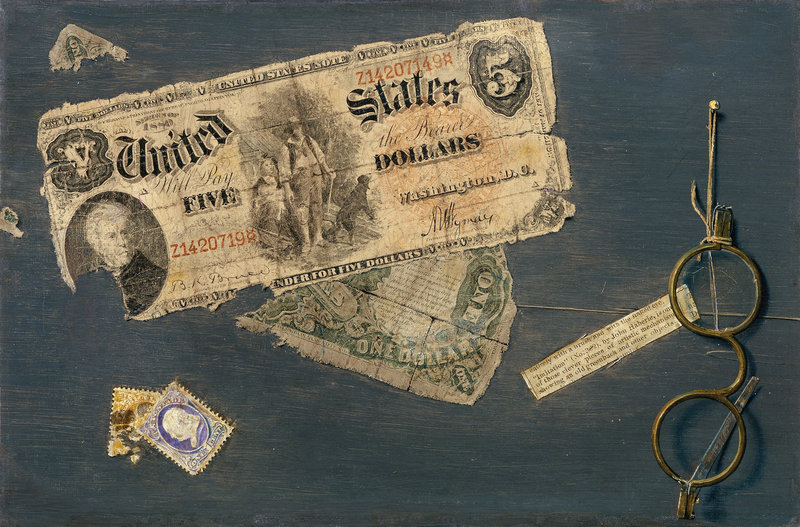

The best part of the show is the wall on which hang three paintings featuring money and stamps. “Imitation” features a well-worn $1 bill, a similarly wizened 50-cent bill and an assortment of coins and stamps. Haberle’s attention to the textures and details of the frayed edges, creases and torn corners is mind-bogglingly impressive.

These “objects” sit on a trompe l’oeil frame with a tintype portrait of Haberle and the artist’s name nicked from the corner of a newspaper. This painting is about “trust” (paper money as promissory note); being the guy in the picture (Washington beside the humble Haberle — the ultimate master of this fictional world) as opposed to the guy making the picture; and how proof (such as the postmarked stamps or the photograph) can be faked.

Not surprisingly, many viewers suspected Haberle of fraud. One critic was so frustrated by his “U.S.A. (The Chicago Bill Picture),” he accused Haberle of coating actual bills with paint to make them look “painterly.”

I really like Haberle’s clear focus on popular culture and an average American audience. His subjects are the stuff of the common world: money, clocks, letters, newspapers and so on.

When he does touch on fine art, Haberle does so with the acrid irony we see in the “Torn-in-transit” series — pictures of paintings that were wrapped in paper torn in shipment. The “paintings” in these works are intentionally awful.

Clearly, Haberle was commenting on the schlockiness of bourgeois art in America. Unfortunately, however, his eyesight had deteriorated, affecting his production and his quality, which shows in this weak series.

Missing the point of this series, the PMA’s label copy notes one of the depicted paintings was “clumsy,” but commends an uglier one for the effort Haberle put into it. The museum also stumbles when it claims that with his good but flawed “Can You Break a Five?” Haberle “achieved what may be his most impeccable trompe l’oeil composition.” For me, the label’s misplaced bombast is a turnoff.

The late and large works are also disappointing. I couldn’t argue when a friend called “Japanese Corner” an “abysmal eyesore.” The similarly hideous “Night” might be fascinating to other art historians, but to me, it’s pure visual agony.

Besides the money pictures, my favorite is “The Challenge.” It features a Colonial-era pistol hanging on a door with a challenge to a duel: “Nothing but a meeting on the field of honor will satisfy me” The note has been tacked to the door and (impressively) shot five times through the sender’s signature.

Bizarrely, Gertrude Grace Still — the lifelong Haberle scholar who penned the accompanying catalog — gave up on this, hoping “further research may someday reveal the full meaning of one of Haberle’s most perplexing paintings.”

Considering Harnett’s absolutely similar gun on a door in “The Faithful Colt” of 1890, it seems pretty obvious this is between Harnett and Haberle. (As well, there are hints of Haberle, such as the George Washington references).

It’s brilliant theater, and I think it’s pretty clear who wins this duel.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.