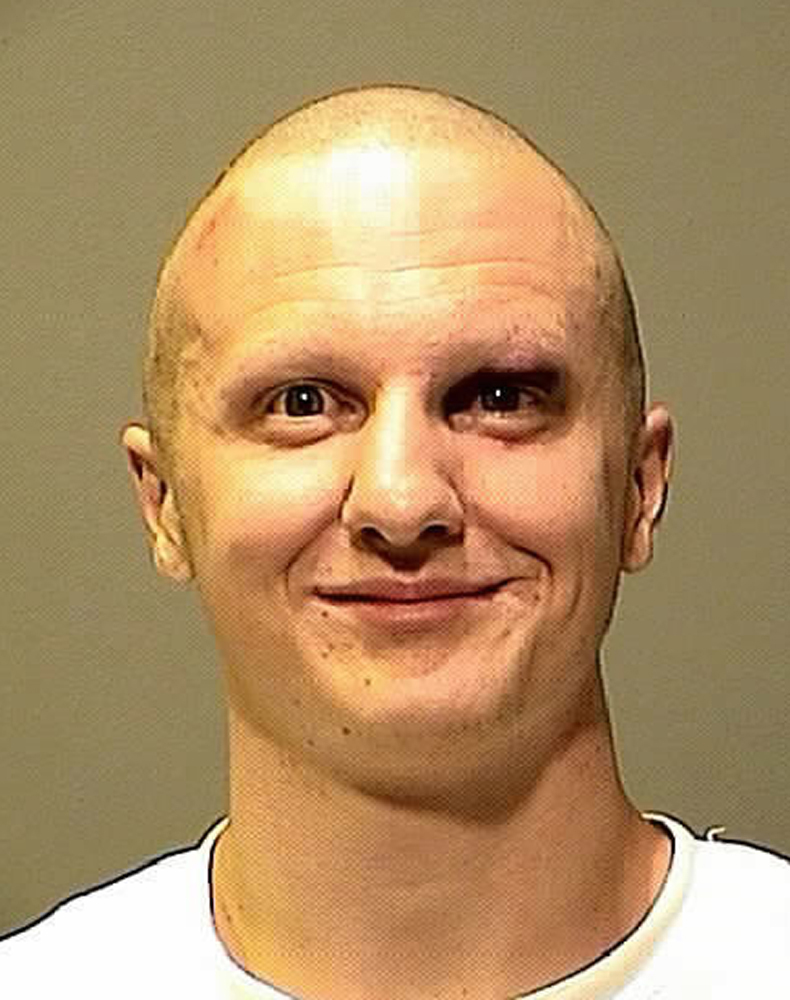

Could a violent outburst like Jared Loughner’s in Arizona happen in southern Maine? Some mental health experts say it is much less likely.

Greater Portland has a program that’s aimed at identifying and intervening in the early stages of serious mental illness in young people, to keep such disorders from disrupting the young adults’ lives.

“About once every year over the last 10 years, we have had a referral where there’s been a threat of external violence — the person is either writing or saying this was just the beginning of something,” said Dr. William McFarlane, research director of the Portland Identification and Early Referral program. “All of them have done very well, and nobody’s gotten hurt. I think all of these have been really close calls.”

The PIER program, funded by a $17 million grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, started in Portland and has spread to five other U.S. cities. It involves training thousands of guidance counselors, school nurses, pediatricians and primary care providers to recognize the early predictors of psychotic illness, which is treated much more effectively when it’s identified early.

A portrait has emerged of the 22-year-old Loughner — accused of killing six people and wounding a congresswoman in Tucson on Jan. 8 — as someone with symptoms of serious mental illness.

In his community college classes, he laughed at inappropriate times, clenched his fists, posed bizarre questions and comments, and exhibited paranoia, warning of government conspiracies. The school ordered him to leave and said he couldn’t return until he got counseling.

It isn’t clear what efforts were made to get him help and whether he was willing to participate in treatment. That is one reason why health care professionals and advocates say recognizing symptoms early is so important.

“There were any number of visible signs of change that a lot of people noticed over time. The point is to intervene when you first notice them,” said Carol Carothers, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Maine.

“Not all violence is preventable, but some violence you could certainly take a good shot at preventing, and this might have been one,” she said. “Like any other illness, the earlier you intervene and treat, the better your outcomes.”

Carothers said the Portland Identification and Early Referral program has become a model nationally for early intervention. Supporting similar initiatives is one of 25 recommendations presented recently to legislators as a way to save money and improve the delivery of mental health services in the state.

Another recommendation is to assemble a quick-response team that can be summoned whenever someone identifies a person showing symptoms of psychotic illness. Team members, drawn from disciplines including counseling, education and the criminal justice system, would help a family member, friend or mentor know where to start in accessing the complex mental health system.

“All of those people who could and should be talking to each other and racing forward at the first sign somebody needs some help, most of those people do not race forward,” Carothers said. “We are trained to respond afterward.”

In some cases, that first call could be to PIER, a treatment and research program specializing in services for people 12 to 25 who show early signs of serious mental illness.

PIER was started by McFarlane and others who believe that schizophrenia and other potentially debilitating illnesses could be more effectively treated or even prevented if people got help when they started showing signs of serious mental illness.

Those signs might include hearing voices, having anxiety around crowds or disregarding personal hygiene and appearance.

“If those events we read in the press are accurate, if (Loughner) had been at Southern Maine Community College or the University of Southern Maine, that person would have been referred and probably seen in the PIER program, almost without a doubt,” McFarlane said. “His behavior was very erratic.”

Dr. Kristine Bertini, director of USM’s counseling services, said the faculty and residential staff are trained to recognize signs of serious mental illness. When they encounter it, they walk the student to the counseling center, to be supportive and make that initial contact more certain and less stressful, she said.

“When we are alerted to some kind of psychosis in the community, we make sure other providers are involved so students are getting what they need, so we don’t have a full-blown psychotic episode,” she said.

The school has a behavioral intervention team, including representatives of residence life, counseling, police and the health center, to make sure a student’s needs are being met. The teams are becoming more common on college campuses, largely because the college-age population is at highest risk for schizophrenia, she said.

In some cases, the student is referred to PIER.

Like other preventive medicine, the PIER model faces challenges under the current health insurance reimbursement system, McFarlane said. However, the Health Care Affordability Act did allow children to be covered under their parents’ insurance until age 26, increasing the chances that young adults can get mental health services, he said.

The program is now full and not taking new patients, though it still conducts assessments and refers people to other providers, McFarlane said. PIER is expanding to accommodate people as old as 30 and those who have had a psychotic episode within the past two years. However, the program’s grant funding could run out this year, and its future is uncertain.

Staff Writer David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.