WASHINGTON – David S. Broder, 81, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for The Washington Post and one of the most respected writers on national politics for four decades, died Wednesday at Capital Hospice in Arlington, Va., of complications from diabetes.

Broder was often called the dean of the Washington press corps — a nickname he earned in his late 30s in part for the clarity of his political analysis and the influence he wielded as a perceptive thinker on political trends in his books, articles and television appearances.

In 1973, Broder and The Washington Post each won Pulitzers for coverage of the Watergate scandal that led to President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation. Broder’s citation was for explaining the importance of the Watergate fallout in a clear, compelling way.

He covered every presidential convention since 1956 and was widely regarded as the political journalist with the best-informed contacts, from the lowliest precinct to the highest rungs of government.

Former Post Executive Editor Benjamin C. Bradlee called Broder “the best political correspondent in America. David knew politics from the back room up — the mechanics of politics, the county and state chairmen — whereas most Washington reporters knew it at the Washington level.”

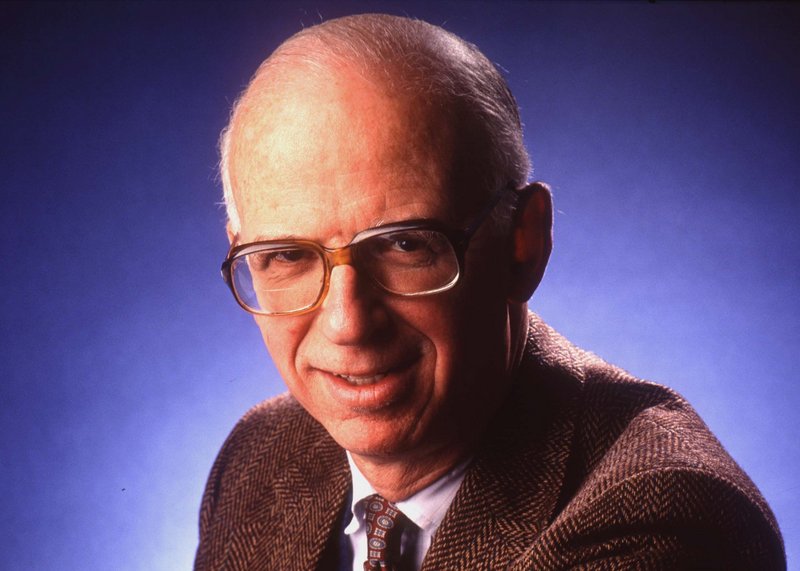

Broder was praised at the highest echelons of political power. Former Vice President Walter Mondale said Broder was the “pre-eminent political journalist and columnist in the country. He was the best. He was solid and careful. His sources and his understanding were so deep.”Balding, sporting horn-rimmed glasses and measured in his speaking style, Broder was a frequent and instantly recognizable panelist on TV news discussion shows, a penetrating questioner who often put politicians on the spot and a clear-eyed analyst who could cut to the heart of an issue.

On “Meet the Press” in 1987, he probed whether then-Vice President George H.W. Bush, the GOP frontrunner in the next year’s White House race, was too much an Eastern patrician to understand average Americans.

Broder asked the candidate whether he knew how many Americans lacked health insurance and how many U.S. children were born into poverty.

Bush said he didn’t know, adding: “We have the best medical-attention system in the world, and I don’t want to see it go into the mode of England or this whole concept of socialized medicine where the government provides absolutely everything. You are going to break the government.”

Broder had genuine admiration for Bush but explained that the questions were important because “even more than most of your rivals, I think you’ve lived in a very special world. Certainly in the last seven years. And I want to try to sort of test how much you understand about some of the realities for the people in the country that you seek to lead.”

Former Washington Post Executive Editor Leonard Downie Jr. said Broder was less concerned with being a “scoop artist” than focusing on a larger portrait of contemporary politics. For two generations, he was among the earliest to spot the rise and fall of political stars, and to identify trends such as the move toward ballot initiatives for states on emotionally charged issues such as gay rights and doctor-assisted suicide.

The plainspoken Broder disliked the influence of political consultants on Washington journalism and their desire to control how news is spun. He preferred to give voters a more prominent voice in the coverage of politics and campaigns.

“I’ve learned that the most undervalued, underreported aspect of politics is what voters bring to the table,” he told Washingtonian magazine.”Given the American people’s deep skepticism about our political system today,” he added, “we can raise their faith some if we give them the feeling that, at least at election time, the press and candidates are responding to their thoughts and views.”

In a syndicated political affairs column that reached 300 newspapers, Broder was credited with popularizing political ideas and debate coming from academic circles.

“I can’t think of any columnist of a major newspaper who took academic political scientists more seriously than David Broder,” said Ross Baker, a Rutgers University political science professor and an authority on congressional politics.

Broder, he added, was able to “reach beyond the dispensers of political wisdom in Washington and tap into a totally different plane than day-to-day commentators in Washington. … He could traffic in day-to-day gossip with the best of them, but his eyes were set a little higher, to look at broader trends.”

His books included “The Party’s Over: The Failure of Politics in America” (1972), which argued for reforms in the two-party system to combat “a rising tide of distrust of government and public officials”; “The System” (1996), in which Broder and journalist Haynes Johnson examined the failure of President Bill Clinton’s health-care reform agenda; and “The Man Who Would Be President” (1992), based on articles he wrote with Post reporter Bob Woodward about Vice President Dan Quayle, who was widely perceived as a lightweight.

David Salzer Broder was born Sept. 11, 1929, in Chicago Heights, Ill., where his father was a dentist. The younger Broder became a Chicago Cubs enthusiast and, in time, a member of the Emil Verban Memorial Society, a group of Cubs’ fans whose chief activity was to commiserate about the team’s historically pitiful record.

At 15, he entered the University of Chicago, where he received a bachelor’s degree in 1947 and a master’s degree in political science in 1951.

As editor of the student newspaper, Broder became fascinated with politics. The paper was being split by two factions, self-described liberals led by Broder and a group of students with communist leanings.

“Both sides used the classic tactics,” Broder told journalist Timothy Crouse of the political struggle at the paper. “Come early, stay late, vote often, pack the staff with your people, and always find an acceptable stooge to front for you.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.