The seamstresses were just getting off work that Saturday, some of them singing a new popular song, “Every Little Movement (Has a Meaning of Its Own),” when they heard shouts from the eighth floor just below. They saw smoke outside the windows, and then fire.

As David Von Drehle recounts the ensuing catastrophe, in his award-winning book “Triangle,” just a couple minutes later the ninth floor was fully ablaze.

The fire engines that rushed to the scene did not have ladders that reached to the ninth floor. The fire escape — which didn’t reach all the way to the street anyway — was not built to accommodate more than a few people and soon collapsed.

The stairwell that led to the roof was already burning, and after a few minutes was consumed by flames.

The other stairwell led down to the street, but the door was padlocked from the outside so that the men and women who worked at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company would be compelled to use just the one stairwell or the two elevators to exit, lest any of them elude inspection and make off with leftover scraps of cloth.

The elevator operators made runs up to the ninth floor several times before their cables stopped working, and before desperate workers sought to escape by jumping down one of the elevator shafts, hoping to find a softer landing atop the descending elevator than on the sidewalk nine stories down.

But many, facing the choice of death by fire or death by impact on the city streets, chose the latter and leapt. Down they came, some already engulfed in flame — first a few, then a torrent, before the horrified crowd that had gathered by the building, which was just off Washington Square in the heart of New York’s Greenwich Village.

When it was over, 146 people had either died by fire or jumped to their deaths. Most were young women, almost entirely Jewish or Italian immigrants, many still in their teens, one just 14.

That was 100 years ago Friday — March 25, 1911. But the battles that arose in the wake of Triangle over worker safety, worker rights and whether government should regulate business are with us still.

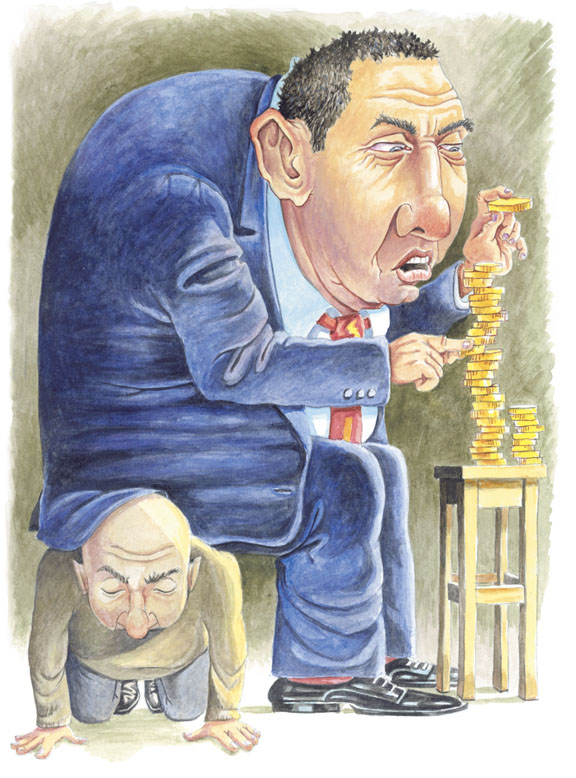

Triangle’s owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, had fiercely opposed the general strike of Lower East Side garment workers two years earlier and had hired thugs to beat up their seamstresses when they picketed the plant.

They rebuffed the union’s demand for sprinklers and unlocked stairwells — and when these facts became widely known in the fire’s aftermath, outrage swept the city. Blanck and Harris were tried for manslaughter — but acquitted in the absence of any laws that set workplace safety standards.

But standards were on the way. In Triangle’s wake, and facing the prospect of losing New York’s Jewish community to an ascending Socialist Party, Charlie Murphy, who ran Tammany Hall and controlled the state’s Democratic Party, told two young proteges — Assembly Speaker Al Smith and state Senate President Robert Wagner — to make some changes to New York’s industrial order.

Aided by Frances Perkins, the daughter of Mainers and at the time a young social worker who was in Washington Square looking on in horror as the seamstresses jumped to their deaths, Smith and Wagner visited hundreds of factories and sweatshops.

Over time, they authored and enacted legislation that required certain workplaces to have sprinklers, open doors, fireproof stairwells and functioning fire escapes; limited women’s work weeks to 54 hours and banned children under 18 from certain hazardous jobs. (Years later, Wagner, by then a U.S. senator, authored — with help from Perkins, who had become labor secretary — the legislation establishing Social Security; he also wrote the bill legalizing collective bargaining.)

Businesses reacted as if the revolution had arrived. The changes to the fire code, said a spokesman for the Associated Industries of New York, would lead to “the wiping out of industry in this state.”

The regulations, wrote George Olvany, special counsel to the Real Estate Board of New York City, would force expenditures on precautions that were “absolutely needless and useless.”

“The best government is the least possible government,” said Laurence McGuire, president of the Real Estate Board. “To my mind, this ‘the post-Triangle regulations’ is all wrong.”

Such complaints are with us still. We hear them from mine operators after fatal explosions, from bankers after they’ve crashed the economy, from energy moguls after their rig explodes or their plant starts leaking radiation.

We hear them from politicians who take their money. We hear them from Republican members of Congress and from some Democrats, too.

A century after Triangle, greed encased in libertarianism remains a fixture of — and danger to — American life.

Harold Meyerson is editor-at-large of American Prospect and the L.A. Weekly.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.