Harry Shearer wants you to know that New Orleans’ devastation from Hurricane Katrina wasn’t a natural disaster.

It was a man-made one.

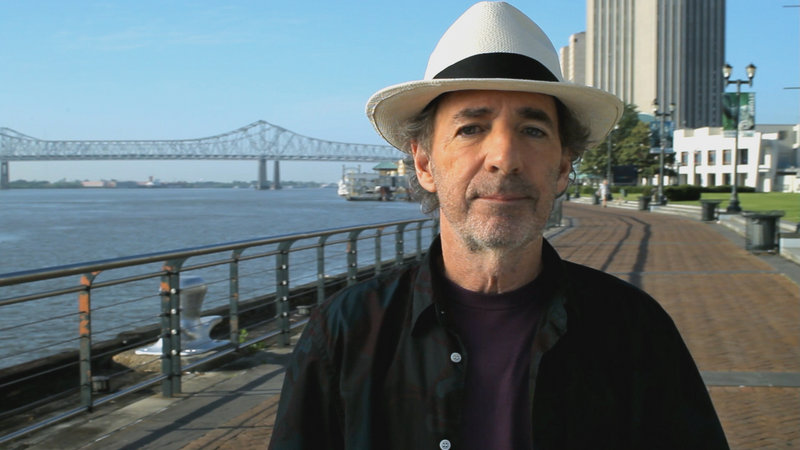

In Shearer’s compelling new documentary “The Big Uneasy,” playing at 7 and 9:15 p.m. today at the Nickelodeon in Portland, he makes the case that the failure of the city’s storm defenses and the resultant extent of the damage can be traced directly back to shortsighted environmental policy, governmental neglect and decades of misguided planning from the Army Corps of Engineers.

Eschewing the self-aggrandizing exhibitionism of such activist documentarians as Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock, Shearer instead crafts a thoughtful, wryly funny portrait of the reasons New Orleans was so shattered by Katrina and how the independent investigators who uncovered the ACOE’s inadequacies were hindered, harassed and ultimately shunned.

Shearer’s long showbiz career includes his legendary comedic work on TV’s “The Simpsons” and in movies such as “This Is Spinal Tap” and “A Mighty Wind.” But he has also been a lifelong political satirist with several books, regular pieces on NPR and “The Huffington Post,” and the long-running radio series “Le Show.”

I recently spoke to Shearer from Los Angeles via telephone.

Your film makes a very compelling case that the defenses protecting New Orleans were inadequate, and you place much of the blame squarely on the Army Corps of Engineers, especially regarding the massive and notoriously misguided Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (known as MRGO). What do you feel is the problem with the Corps?

As to why the Corps is the way it is, a few months ago, a State Department official was quoted as saying that “they have a culture of impunity,” referring to Afghanistan. It’s the same with the Army Corps of Engineers. When one of their projects fails, their answer is that they only do what they are directed to do by Congress. But they are the ones to pitch the projects to Congress in the first place, and Congress has no other outside authority to consult. There is an insularity to the system that precludes independent oversight, outside opinions. They have a monopoly on public works, especially with regards to water projects. You can’t expect them to get better when there’s no disincentive to getting worse.

In an age when information is as available as ever, it’s pretty shocking that many people still believe that the levees were simply overwhelmed, rather than, as your film documents, that they were undermined because of poor design. Do you attribute that fact to official misinformation, journalistic sloppiness (or) lack of public attention span?

The age we live in is an information/infotainment/disinformation age. They’re all out there, and there’s no handy-dandy guide to what’s actually true. It’s as if you went to the supermarket and there’s food, food-like substances and poison, all packaged similarly, and there’s no way to tell which is which. In that environment, what gets across is due to luck and money (which can package data better), and the perceived authority of the source. Most of the media was easily led. It is the media’s job to ask “are we being told the whole story?” People with 9-to-5 jobs, and a wife and four kids, when they get home from work, it’s not necessarily what they’re going to do. You turn to professionals.

What journalists/organizations do you feel did a good job uncovering the truth about Katrina?

The New Orleans Times Picayune, which won two Pulitzers. The Gambit Weekly in New Orleans. John Schwartz at the New York Times. Michael Grunwald at the Washington Post. That’s pretty much it. On the other hand, there were all the people who congratulated themselves, like Anderson Cooper wagging his finger at (Louisiana Sen.) Mary Landrieu, thinking that was doing something. The national media fell for the Bush ploy of dangling (former FEMA head) Michael Brown out there as a sacrificial pinata.

A book like Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States” is like a roll call of those whose contributions to U.S. history were excluded from the official version. In “The Big Uneasy,” you champion three people who challenged the government line and paid for it. Is it the essential nature of a society to graft a simplistic narrative onto complex events?

I think it’s the essential nature of nationalistic mythmaking. Look, on a macro level, we’re a country which on one hand had a bunch of very smart people at the beginning to write a very clever and intelligent document, and lurched toward giving people the rights guaranteed at the beginning. On the other hand: slavery, genocide, dabbling in imperialism. How do you get people to stand up and cheer? It’s easier to whip up nationalistic sentiment. That’s what every nation state does; it composes a partial narrative.

You choose not to put yourself in the middle of your documentary. Did you feel doing so would undermine the film?

I was very concerned about that. The first cut of film had not a frame of me in it, but test audiences said they needed someone to point the way. I’m not claiming it was my opinion, but I felt my job was to overcome four to five years of misinformation, to get people who know what they are talking about. These are people telling their stories. I felt that that was really crucial in creating a connection between them and the audience, and getting across a massive amount of data without dumbing it down. Believe me, nobody walked past the engineering building faster than I did in college.

Dennis Perkins is a Portland freelance writer.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.