One of the most famous, beloved and — indeed — powerful paintings in the world is Salvador Dali’s surrealist masterpiece, “The Persistence of Memory.” The iconic painting depicts a dreamy landscape in which even clocks are so mellowed that they melt in sleepy repose.

I have seen it many times at the Museum of Modern Art and watched dozens of viewers react to it. While the image is amazing, uncanny and fascinatingly weird, the only thing people say is that they can’t believe how tiny it is.

“Intimate Abstraction” at Rose Contemporary is a show dedicated to the effects of intimacy in small works of art. It’s a terrific show right out of the gate — while there are more than 30 works on the wall, the installation is comfortably quiet because it gives all the work space to breathe.

As well, the paintings, drawings and collages are all nicely framed and presented. I was particularly impressed by a puce rectangle painted on the wall in which Ling-wen Tsai’s six tiny sumi ink drawings on paper are directly pinned. I am not sure it will help viewers imagine the works in their own homes, but it looks great in the gallery.

Several of the artists are quite well known or have had their works shown recently in Portland, so it’s a treat to compare what you know of them to the work selected for an exhibition devoted to intimacy and diminutive scale.

My favorite contrast is the work of Clint Fulkerson, a bright young artist (with a great future ahead of him) whose giant wall painting at Space Gallery was one of my favorite pieces shown in Portland this past year.

Fulkerson is even better tiny. His four ink drawings (beautifully mounted on panel) thrive on delicacy and call you in to view them as closely as possible. Yet, despite seeing them from inches away, his two wash drawings never quite reveal themselves. They almost look like inked pencil shavings flattened onto the paper.

It’s not that you need to know how Fulkerson made the pieces, but the fact that they pull you in and hold you to wonder if he taped and wet the paper, etc., quietly compels the viewer to think in terms of process — and process itself is absolutely at the heart of the content of the pieces. They are unusually successful in pairing clarity with mystery — a combination often at the core of the greatest works of art.

I was pleased to see Penelope Jones’ work in the show. Most of her works in casein (a water-based paint that can be used like gouache or watercolor, or even glazed like oil) strike an odd pose between being paintings and being so small that they look like studies for larger paintings. Instead of feeling like broken miniatures, however, the effect is playful. Moreover, Jones can paint so well that her pieces hold up under very tight scrutiny.

However, Jones’ full-sized “Shift” probably doesn’t help the plight of her smallest pieces by dint of being the most handsome piece in the gallery.

I think the best pieces in the show for illustrating curator Ginny Rose’s ideas about intimacy and abstraction are tactile collage works by Judith Allen-Efstathiou and Henry Wolyniec.

Allen-Efstathiou’s works are on cloth that has been cut and sewn together as well as worked with paint and ink. They have the feel of ancient papyrus at first glance and then something somewhere between cubism, tattered rags and high fashion when seen up close. (I say “high fashion” in the sense that Allen-Efstathiou has a sophisticated clothing designer’s feel for texture, color and detail.)

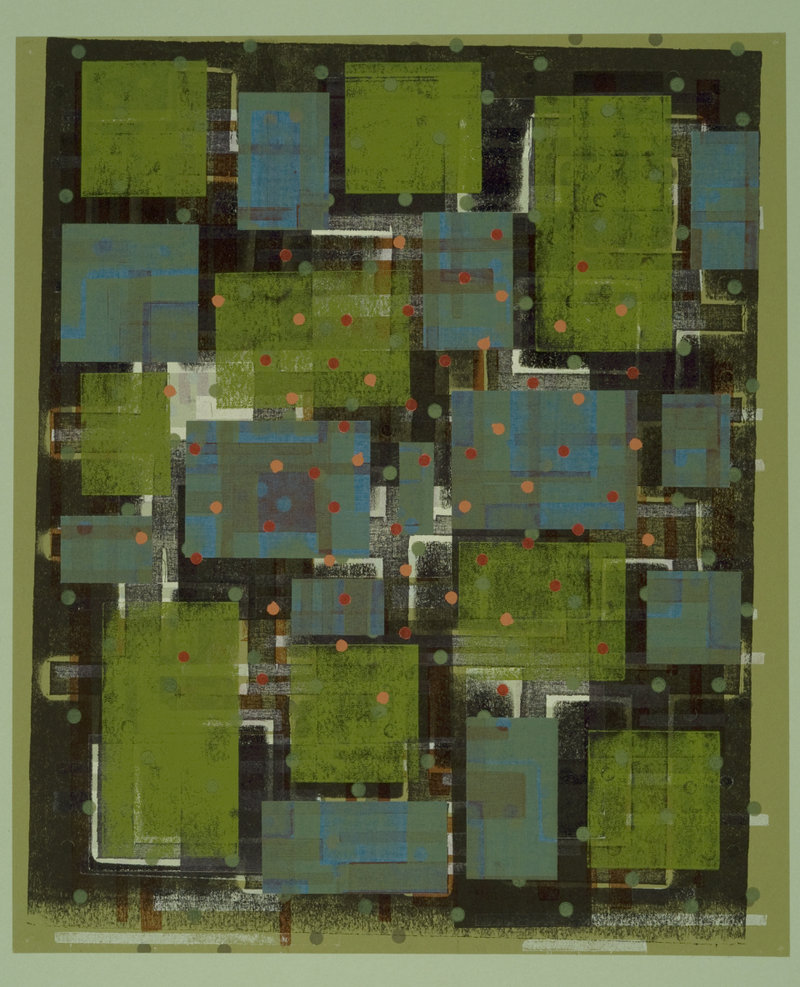

Wolyniec is my favorite find in “Intimate Abstraction.” It’s not that I had never seen his work, but I had certainly never seen it this way. His abstractions are energized, blocky forms that build up from the center of their paper support. They have an almost architectural logic save for collaged forms rhythmically placed over the image that almost force your eye to jump around.

Some of the collage forms are paper-punch dots (I also like his piece made with hole-punched rectangles), while others look something like cloth tape that has been inked maroon and drawn over in pencil. These are lively and completely abstract, and they exude not only visual intelligence but an enjoyably sparky wit.

“Intimate Abstraction” is about getting up close to art and the difference it makes to stand away from it. Rose successfully makes the point that there can be much to see no matter where you stand — but that sometimes it really pays off to look closely.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story