When Steve Hoad and his daughter Rose began producing as many as 2,000 to 2,500 chickens and turkeys on their Windsor farm, they thought it might be a good investment to build their own slaughtering facility to process their birds for market.

Under state regulations, they would be able to sell the birds at their farm, through community-supported agriculture, or CSA, programs, and wholesale to restaurants and stores.

But after doing a lot of research and crunching some numbers, the Hoads concluded that the project didn’t make sense financially.

“Yeah, we could build a garage and slap something in there, but that’s really not doing it right,” Steve Hoad said. “We estimated it would take $39,000 to $55,000 to build a facility that would be reasonable and we could keep clean. Then you would also have the issue of labor.”

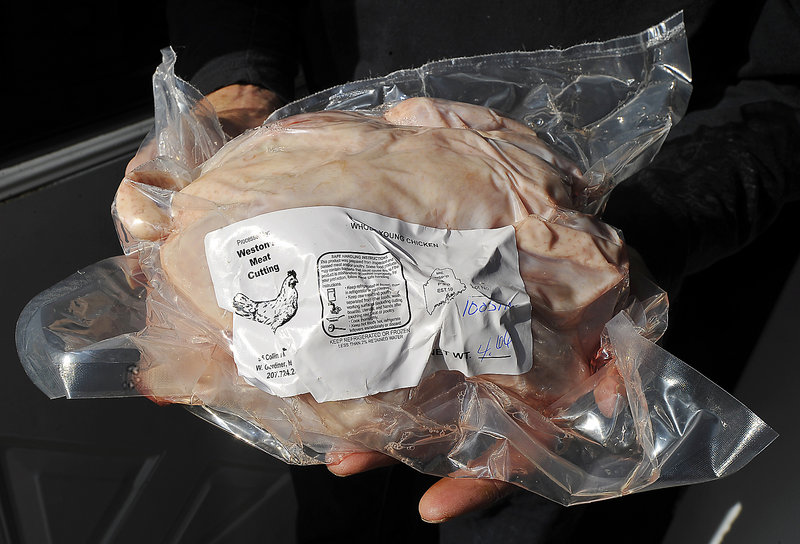

The Hoads ended up going to a state-inspected facility in Monmouth. When that closed earlier this year, they started taking their birds to Weston’s in West Gardiner, which is now the only poultry processing facility in the state that has on-site state inspectors.

It’s a more expensive way to bring their poultry to market, and for producers who live more than 50 miles away, it’s impractical — and more stressful for the birds. It doesn’t help that there’s a shortage of inspectors, although state regulators say they do their best to accommodate farmers’ schedules.

“People Down East are having a real hard time,” Hoad said, “because unless they are doing (processing on their farm), they have to haul all the way down to West Gardiner.”

Poultry was once a major part of Maine’s agricultural economy, said Mark Lapping, executive director of the Muskie School of Public Service and a professor who has studied food processing issues in the state.

“We’ve always been a very, very important chicken state in terms of meat,” he said. “In fact, in Belfast, a lot of people think that the facilities at the harbor was for this or that, but it was for the export of chickens. Belfast was a major chicken exporting area for Boston and other areas as well.”

Today, with more people concerned about the country’s industrial food system, the demand for local meat has skyrocketed. More Mainers are getting back into farming, and those small farms are starting up poultry operations.

But getting their products to consumers can be challenging.

“Right now, given what we have in infrastructure and inspection, it’s really hard to see the sector really growing significantly,” Lapping said. “I suspect a lot of folks would like the state to get involved in helping put together a strategy or more facilities, and at the same time they don’t want the state to regulate it.”

‘A BIT TOO SMALL’

Hal Prince, director of the Division of Quality Assurance and Regulations at the Maine Department of Agriculture, says local poultry production has grown to the point where the state could probably use several slaughter facilities dedicated to poultry, “but it’s still a bit too small for that to become a reality.”

The state currently has 3½ state inspection positions, and has just been given approval to hire a fourth. There’s enough work for probably double that number, Prince said.

There are 18 facilities in Maine licensed to process poultry. In addition to the Weston plant, where birds are individually inspected by a state inspector, there are 13 facilities like the one the Hoads wanted to build.

Those facilities can process up to 20,000 of their own birds a year, but are not allowed to process birds from other farms. They are allowed to sell their birds retail at their farm or through farmers markets and CSAs, and they can sell wholesale to restaurants and stores.

While the state must approve of the operations through regular inspections, they are exempt from continuous, bird-by-bird inspections.

There are four facilities that are allowed to slaughter up to 1,000 birds a year. These producers have fewer space and equipment requirements than the 20,000-bird facilities, but they can only sell birds to customers who come to the farm, at farmers markets or through CSAs. They are not allowed to sell to restaurants or stores.

The facilities that can process up to 20,000 birds are “really what small farmers have to go for if they want to have an economically viable poultry operation,” said Chad Conley, who manages the Miyake Farm in Freeport.

“If farmers are trying to raise chickens for meat and actually make money on it — not have it just be this nice thing they do on the side — it’s the only option that allows you to make money, because it costs $4 a bird to have somebody process your bird in a state-inspected facility,” Conley said. “And that’s basically half your cost of raising the bird, so you can’t really make any money.”

But setting up an on-farm slaughtering facility, Conley added, could cost as much as $30,000 to $40,000 up front, “and most farms just don’t have that kind of money.”

Conley is also puzzled by the fact that people who have 20,000-bird facilities must get a separate license as a custom processor if they want to process other people’s birds.

“I’m not against regulation,” he said. “I think there are absolutely legitimate safety concerns when it comes to handling food, and meat especially needs to be handled properly.

“But the state just goes way too far. It makes it very difficult for people to operate and make money doing this.”

DODGING THE RULES

The result, poultry producers say, is that some farms sell their birds illegally or find creative ways to get around the regulations.

“There are actually some farms selling their birds live,” Hoad said, “and then the people that buy those birds have to pick them up at the slaughter plant.”

Some smaller poultry producers who have revolted against state regulations say their customers know and trust them to run a clean operation, and that should be enough. Last spring, several communities on the Blue Hill peninsula passed local ordinances that would exempt farms from state and federal regulations if they sell directly to their customers.

Shortly after, the state agriculture commissioner asked Maine’s attorney general to send the communities a letter informing them that state law pre-empts their local ordinances. The letter stated that anyone who fails to comply with state law could be barred from selling his products or be subject to fines.

Prince said that if people are caught selling illegally, state regulators try to work with them first to bring them into compliance. Only if they absolutely refuse to do anything differently are they subject to a fine, and the amount of that fine would be determined by the attorney general’s office.

“But that’s not the way we choose to do it,” he said. “That’s an absolute last resort.”

ONE BAD BIRD …

Not everyone agrees that knowing your farmer is enough to keep poultry safe. Hoad said he and other poultry producers are worried about the farms working outside the law because one bad bird that makes someone sick could bring down everyone else.

“All of these licenses are basically set up to protect the consumer,” Hoad said. “And you know, just because the consumer knows their farmer doesn’t mean that farmer knows the science. I can raise the cleanest poultry in the world as a farmer, but if I don’t know the science about processing and how to control the pathogens that are involved, I can make a mistake at the end as I process those birds that would kill somebody.”

Similarly, some producers say the process of complying with the regulations that protect public health needn’t be so costly.

“I think people are scared off,” Prince said. “I’ve heard those stories too, about ‘Oh, it’s going to cost me $30,000 to get the type of facility that’s required.’ But that’s not what I’ve seen in actual practice. It can be done, and we’ll work with them.”

Ryan Wilson of Common Wealth Farm in Unity raises Pekin ducks and silver cross gray broilers. He raises 3,000 birds a year, and sells them at the Portland winter farmers’ market and to Hugo’s, Fore Street, Cinque Terre, Rosemont markets and Local Sprouts.

Wilson built his slaughtering facility in a corner of his barn, in a raised area so he could install plumbing without digging. The wastewater goes into a tank and ultimately is spread on his fields. The walls are plywood. He did it all, including the equipment, for under $10,000.

“All they want is something that is safe, that can be washed, and that you produce a product that’s not going to hurt anybody,” he said.

Wilson thought of it as an investment in his business, the way a vegetable farmer might invest in a new tractor. He said he thinks a lot of small Maine farms are actually “quasi-homesteaders” who are trying to do everything.

“I think that people don’t understand that there’s an economy of scale that needs to happens with agriculture to make the changes that we need,” Wilson said. “I really believe in a lot of small-scale homesteaders. I think that’s a great culture to have in America.

“But I think as far as changing the food system so that people can eat more locally produced food, we need to step it up a little bit in terms of size. And I’m not talking hundreds of acres. I’m talking about efficient agricultural productions that are both ecologically and economically efficient.”

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at: mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story