‘Portraits” at Addison Woolley Gallery is an unusually challenging show. It’s also a challenged show. It features difficult photography-based work. On Washington Avenue in Portland, it’s off the beaten track. The artists, Sally Dennison and Mat Thorne, are new to Portland. And it’s small: There are only 16 works between two artists.

Yet I saw it twice, and one of those visits took more than an hour. There is much to see and even more to think about.

Dennison uses photography to transform herself into different characters. Thorne digitally places vertical swaths of film stills to create facial portraits of male archetypes such as cowboys, criminals or soldiers.

The obvious specter towering over this show is Cindy Sherman and her blockbuster series of self-portraits known as the “Film Stills.” What’s nice is that the Sherman reference is so obvious yet so revealing if you pursue the connection.

Sherman’s photos typically feature the attractive artist dressed and posed in recognizable scenes from well-known movies. While they address issues of identity, they more broadly touch on the idea of fantasy self-imaging and the relationship of the single photographic image to scene or movie-length narrative.

Dennison’s images, on the other hand, move well past Sherman’s preferred 1950s-era aesthetic to something closer to campy 1980s portraits with a heavy dose of David Lynch-style uncanny discomfort. Her portraits generally show herself not as some starlet about to be attacked by marauding crows, but rather as commonplace geeks you forgot about until you saw their high school photos so many years later. (I am dating myself, but that’s the point.)

Dennison’s images are immediately weird, but they only get creepier the closer you look, because she tweaks them (masterfully) in Photoshop. It’s the artist in all of the images, but on closer inspection, the eyes are several colors, noses vary, the model’s weight is different and so on. Sometimes these changes are minor, but many aren’t the kinds of things that can be easily shifted without great effort and skill.

Dennison’s “Theresa,” for example, depicts the artist in a polka-dot bathing suit pressed up against a patterned dot wall of fabric. The frontal figure is a homely and rather uncomfortably underdeveloped woman of about 35. She looks down and away from the camera as though posing is something of an embarrassment endured. Her mousy hair is greasy. Her body language is desolate.

The power of “Theresa” is that it invokes a response as though your gaze was the instrument of abject cruelty that pushed her spirit to its current, damaged state. It’s something beyond pity. It’s more personal, as though you are somehow responsible. (Of course, as the photographer, Dennison was.)

Dennison’s “Erma,” on the other hand, depicts a slender, mod and confident youth in three-quarter profile pose. Between the blond hair and the figure’s affectedly aquiline nose, it’s hard to see how these two images could be of the same person — except by looking at the rest of the images.

“Erma” also features an intensely considered relationship between the figure’s shirt and the fabric covering the wall. Such texture relations add an overly vivid weirdness to the image, and yet also give Dennison a chance to explore textures and patterns like the skilled photographer she is. This is particularly important in my favorite of her works, “Pattie,” in which the figure is a pre-pubescent girl with a blank affect in sort of a Nike of Samothrace pose.

What is odd about the photo is not obvious. To begin, the light blue fabric of the dress is similar but not the same as the wall fabric. Her arms, drawn back, seem to look strange because of their angle, but it’s more that Dennison took advantage of the pose and the distortion of the camera to quietly over-extend the length of her arms.

Dennison’s characters are quirky enough to exude personality or individual story simply by means of a single portrait photograph. They force many interesting — though often uncomfortable — questions about how we project identity onto others.

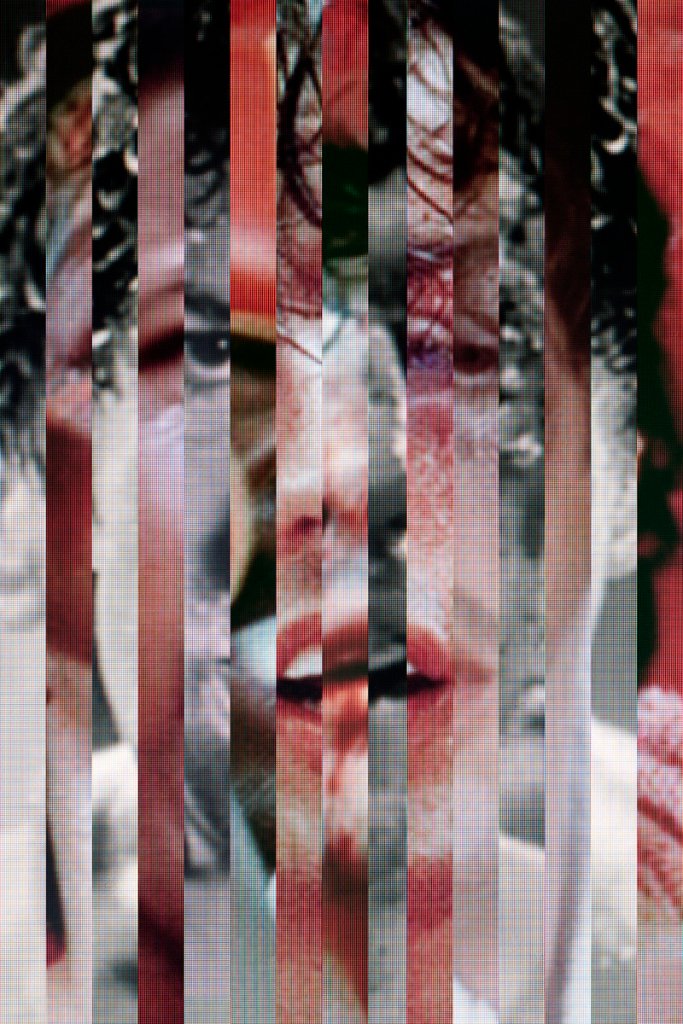

Thorne’s all-male movie set-piece portraits with a solid 1970s cast make for quite a pendant to Dennison’s twistedly introverted femaleness. Rather than individuals, Thorne presents recurring types made from vertical strips of images from at least six different movies per image.

I can’t stand the idea of eternal “archetypes” (they are often tools of oppression), but while Thorne overtly employs them, I don’t see that he’s defending the notion.

Is Thorne’s work photography? Digital print-making? Or some kind of film-based work? His process is interesting to consider, given that you can imagine him scanning his own memory for images to hunt down in movies he saw long ago. He must then get the films on DVD and grab the images — more Photoshop.

Thorne’s maniacal “Cowboy” is the most eye-catching, and yet the most easily understandable — the good, the bad and the ugly all in one. His “Boxer” uses the blood coloring of brutalized faces to make a strangely beautiful image.

His best, however, is “Astronaut,” because the squarish format and echoed details — such as the reflections on the helmet glass — wind up delivering a visually coherent yet emotionally varied set of facial expressions.

While I was initially drawn more to Dennison’s uncanny images, Thorne’s archetypes are far more likely to lead to interesting conversations. And yet they are both better for being together: Identity as composite; archetypes as cultural creations; individuality versus character; self-portraiture as inversion; and so on.

“Portraits” is a little show, but it offers much to see and even more to think about.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.