There is propaganda. There is art that is political. And then there is art about political structure.

The work by the five artists in “Not the Usual Politics” at Rose Contemporary in Portland falls largely in the last category, but with a solid dose of political art as well.

It is a handsome and thoughtful show that largely hits its target of excavating underlying ideas about political perspective.

Greg Murr’s fascinating watercolor and pastel drawings feature groups of dogs. Some of the (stenciled?) dogs repeat throughout the four pieces and even find regular places. One dog with a circular tail is on the right in all four images, and most have the same dog on the left, facing inward with its nose to the ground. Others are unique.

The repetition of the specific dogs plays up the mechanisms of difference amongst the four images as if they were double blind studies. We see ourselves echoed in the pack logic and animal instincts.

In “Tiergarten” (named after a park in a political area of Berlin), Murr’s dogs surround a tree filled with high-heeled shoes. It’s a strangely loaded image. The shoes could represent the sort of lustful indulgence of the biblical apple in the Garden of Eden or the contemporary fetishizing of shoes as the ultimate shopping target — or both.

Annie Bissett’s woodblock prints are divided between images of historical identity politics and prints riffing on the symbolic designs on American money.

“God Blesses John Alexander & Thomas Roberts” is about two men who were convicted of homosexual acts in the Plymouth colony in 1637. Both were whipped severely, and one was banished from the colony. The image shows them posing with arms around each other, surrounded by harsh texts and with the hand of God reaching down to brand them with an “S.” (Records show Alexander was branded.)

The political mechanism of this piece is its assault on the idea that homosexuality is a contemporary affect rather than an eternal historical reality. That the penal records constitute proof is an ironic twist of evidence over anecdote — rather like a hostile witness.

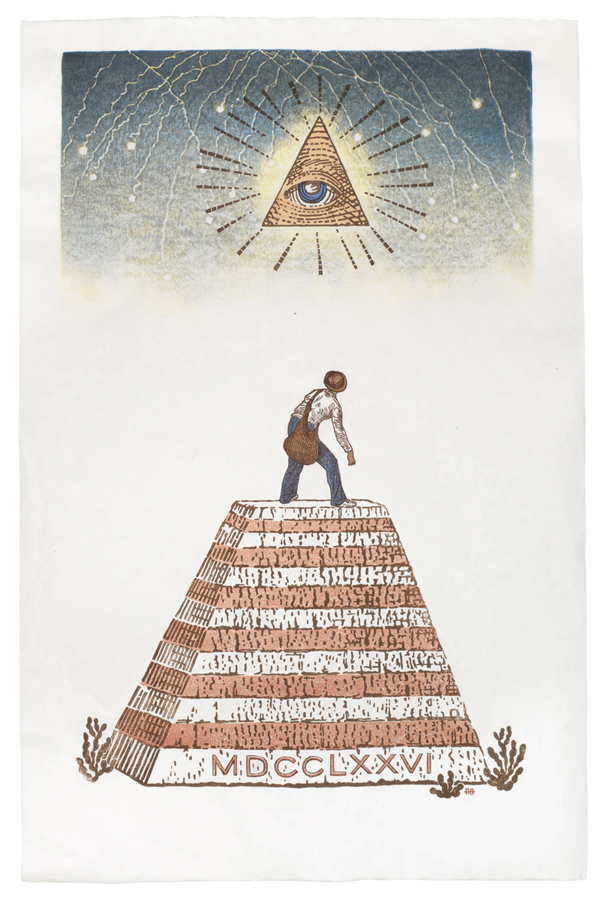

Bissett’s three prints based on elements from the dollar bill are wonderfully fun despite their critical punch. “Pyramid,” for example, shows a figure (between his outfit and dark-skinned hand, he subtly appears to be a slave) standing on the dollar’s pyramid platform under the triangular Eye of Providence — which has been colored with a Caucasian skin tone.

It’s an extraordinarily provocative image, because the Masonic imagery itself is both controversial and little understood. Secret societies like the Freemasons were seen by many as crucial to the Revolution. The Roman numerals for 1776 are on the pyramid, and the great pyramids, of course, were built on the shoulders of slaves. And so, hints Bissett, was America.

I was not impressed by Dan Mills’ phantasmagorical future vision of American imperialism. Mills imagines 48 “future states” based on arguments for imperial annexation gleaned from the CIA World Factbook. The artist puts images of the new states onto found maps — many of which were fascinating before Mills began altering and covering them with his prints, drawings and “US Global (USG)” stamps.

I don’t like this kind of personal mythology in general because of its reliance on its own back story, without which there is little to understand or enjoy.

Amze Emmons’ impressive graphite and gouache works bristle with an architectural intelligence. While they offer meditation on the plight of refugees, they refuse to speak in specific terms.

“Fear of Thunder,” for example, conflates a gatehouse with a Photomat in a place of war-torn strife and its jet-filled sky. The coolness of the 1970s architectural drawing style is alarming — wars aren’t supposed to be so close to where we live.

Adriane Herman only has two pieces in the show, but one of them is truly powerful: “I Didn’t Know It Was Loaded.”

The scratchboard-style drawing on panel shows a frantic mother using an old-fashioned crank phone. A plaintive boy in a play Indian headdress tugs at her arm. Behind them lie a limp girl on a couch and a revolver on the ground in front of her.

Herman’s point seems to be the form of the argument, since her obvious target — the NRA — tends to traffic in hypothetical anecdotes, such as “I would rather have a gun in my hand than a cop on the phone,” rather than broader notions of likelihood.

“Not the Usual Politics” engages mechanisms of political perspective. Because it’s a small show, it barely scratches the surface of the subject, but it does open doors to thinking much broader than standard American bicameralism.

It is elegant, subtle and well worth a visit.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.