KRASNY YAR, RUSSIA – We are wading through 5-foot-tall ferns that almost bury my 16-year-old daughter. A Eurasian vulture circles above the tree canopy. Below, the forest floor is covered with a blanket of moss so thick it’s like stepping on a waterbed.

“It’s a lot like Maine, except bigger, and more dense, more bugs, more of everything,” my daughter, Ihila, tells me. “I feel like an ant here, really small. I’m waiting for a dinosaur to come crashing through these trees.”

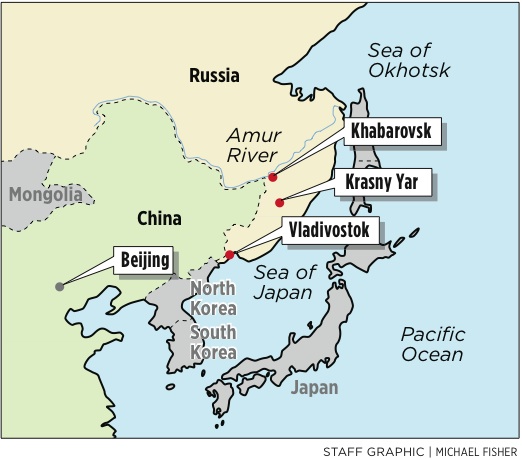

Yes. Waiting for a dinosaur. I remember thinking the same thing when I was hiking through these woods nearly 20 years ago. We are in the Bikin River basin about 300 miles north of Vladivostok in the Russian Far East. The basin is the largest tract of virgin temperate forest in the Northern Hemisphere and home of the Siberian tiger and several indigenous Asian tribes.

The native people and the Amur tiger share this forest. Both the tiger and the tribe face the threat of extinction. In their struggle to survive, the interests of each are protected by the existence of the other. In a sense, they are allies.

We are here because this is where I met Ihila’s mother, Svetlana.

Mom is waiting for us a few miles downstream in Krasny Yar, a village of 680 people, most of whom are ethnic Udeghe, which means “forest people.” Members of other tribes, including Nanai, Evinks and Oroch, also live in the village. You could think of them as the Russian version of American Indians.

The most well-known Nanai is Dersu Uzala, a legendary hunter whose friendship with Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev in the early 20th century served as the basis of a 1974 film by Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. It was filmed near here.

Svetlana is a Nanai woman. I met her at a party at the village school in the last minutes of 1992. She was in costume as Snegurochka, the Snow Maiden, the beautiful pagan deity who lives in the forest and helps Father Frost deliver presents to children on New Year’s Eve.

At the time, I was a journalist living in Russia. I had traveled to the village because its hunters were threatening to shoot at the logging trucks of a Korean company that planned to move into the river basin. The loggers turned around.

Some of you know her as Svetlana Bell, a dressmaker on Main Street in Yarmouth. This month-long trip is the first time she has visited her home village since she moved to Alaska with me in 1995, with her two daughters, Nina, 10, and Sasha, 18. We all live in Maine now.

Our daughter, Ihila, who was born in America, has heard about this remote village her entire life. Growing up in Maine half-white and half-Asian, she often felt out of place. Not here. Many of the village children are mixed-race and look like her.

“It made me feel like I belonged,” she writes in the diary she keeps during our trip.

AN AMAZING AND BEAUTIFUL FOREST

While Svetlana remains in the village with her sister and her friends, her nephew Gresha has taken Ihila and me upriver in his flat-bottomed river boat. The landscape here would seem familiar to anybody from Maine. The Sikhote-Alin mountains roll across the horizon and have the same rounded, tree-covered peaks as the mountains of New England.

The forest or taiga is largely a mix of familiar broadleaf trees, such as oak, hemlock, elm, birch and maple. There are also Korean pine and cedar trees.

Yet the forest is also so different, in its richness and diversity, and in its wildness and vast size. Community Tiger, the village’s community development group, is paying the Russian government 1.6 million rubles — about $50,000 — annually to lease more than 1.1 million acres — an area nearly six times larger than Baxter State Park.

The lease gives villagers the right to hunt game and trap fur-bearing animals, which is how nearly 50 men here make a living. It also allows villagers to harvest non-timber products such as ginseng, Korean pine nuts, wild honey and paporotnik, a fern like the fiddleheads we gather in Maine each spring.

The villagers this year harvested 120 tons of pine nuts and earned enough money to make Community Tiger’s lease payments. They also used the pine nut profits to fund an anti-poaching team. This is the first year the village was able to make the lease payments on its own without the help of the German government, which wants to protect the forest because it’s a significant carbon sink, meaning it absorbs carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

If this temperate forest were in the United States, with its free-market economic system and footloose and ambitious population, it would have long ago been subdivided, first for logging and then ski resorts and vacation homes.

If this area were still part of upper Manchuria, as it was before Russia claimed this territory in the mid-1800s, imagine what the Chinese would have done here. You would be seeing these cedar trees stacked in the aisle at The Home Depot.

That is why this forest is amazing. That it still exists at all.

Shifting wind patterns have created an extremely variable climate that allows for the greatest diversity of wildlife and plant life found anywhere in the world at this northern altitude.

In the winter, the prevailing winds come from the west, across all of Europe, over the arid steppes of Mongolia and the mountains of eastern Manchuria before reaching these mountains, wrung dry of moisture and warmth. From November to March, temperatures stay in the deep freeze, sometimes reaching 30 to 40 degrees below.

This cold weather is why sable and other fur-bearing animals here are so prized. Villagers need their plush fur coats to stay alive.

In the summer, though, the prevailing winds shift and come from the east. Monsoon winds bring heavy rains — including violent typhoons — from the Sea of Japan. The season is warm and wet enough for opium poppies, ginseng plants, lotus flowers, wild grapes, cork and bamboo trees. Giant ladybugs cling to the ceilings and windows in village homes. The crickets are bigger than any I’ve ever seen. Ferns grow high enough to almost bury a person standing up.

The forest is home to both black and brown bears, raccoon dogs, wolverines, leopards, deer, elk and moose, and wild boar.

TIGERS ARE THREATENED

The basin plays a critical role in the survival of the endangered Siberan tiger, known in Russia as the Amur tiger. It is the world’s largest cat, with the average male adult weighing nearly 400 pounds. It is here because of plentiful cedar nuts, which feed the boar, the tiger’s primary prey.

Between 400 and 450 tigers live in the Russian Far East and maybe a dozen live across the border in Manchuria. The Bikin River basin is home to about 50 of them.

Tigers rarely attack people. In 1997, an injured tiger attacked and ate two Russians in the Bikin River basin. Svetlana’s uncle Edik, who lives deep in the forest far above the village, was badly mauled by a tiger a few years ago. I have seen paw prints on two occasions, in the mud along the river and once in the snow on a road near the village. Each print was bigger than my entire hand.

Russian and Chinese poachers hunt tigers, often using live dogs as bait. During our visit, police arrested a Russian man in a town closer to Vladivostok after finding the skins of eight tigers in his home. The tiger’s various parts are sought by the Chinese for their supposed powers as folk medicines and aphrodisiacs. A tiger’s corpse can fetch as much as $50,000 on the black market.

The natives see amba — the Nanai and Udeghe word for tiger — as a near deity. Killing a tiger remains taboo, a violation of a deep cultural value. Just to see amba is considered a sign that one has done something wrong and that one should pray for forgiveness.

“The tigers keep the forest healthy,” Yuri Sun, 51, an Udeghe hunter, tells me. “It’s good that the territory has tigers. They bring balance to the forest. If there were no tigers, there would be wolves, and they would kill everything.”

NATIVE PEOPLE ALSO ENDANGERED

The natives here are Tungusic people related to Manchu people of northeastern China. They are a tiny minority in Russia. While there are more than 3 million ethnic Russians in the region, for instance, there are only 1,700 Udeghe.

The Udeghe language is vanishing from the Earth, spoken now by only about 40 elders. Children know certain words and phrases, such as “bugdifi” (hello) and “loosa” (Russians).

The Soviets banished or killed most native shamans when they gained control of the area in the 1930s. A few survived. Svetlana remembers as a child the frightening drumming and chanting sounds emitting from the home of a neighbor, an elderly shaman who smoked a pipe filled with opium. From his long belt, he dangled a talisman of bones, wood and pieces of metal, creating jingling sounds.

“We were afraid to look at it,” Svetlana tells me. “It was so terrible.”

The shamans are now all dead. Today, a 51-year-old Nanai man in Krasny Yar has announced that he is a shaman. He danced at a community bonfire during our visit, but many villagers believe he’s a fake.

In one important respect — in their relationship with the forest — the natives are holding onto tradition. The men in the village hunt and trap for a living, as they have done for thousands of years, a cultural heritage that sustains them and has allowed them to remain in this mountain valley as a cohesive group.

For now, both the natives and the Amur tigers sharing this forest are holding their own.

“The hunters are fiercely protective of their territories, and Russian law is lenient in situations when a hunter shoots an intruder,” says Evgeny Smernov, a forest ranger with the provincial agency, the Institute of Geography. Smernov, who is married to an Udeghe woman and lives in Krasny Yar, says hunters are protecting their livelihoods, not the tiger. But their vigilance has had the effect of keeping poachers from intruding into the basin.

“As long as there are Udeghe here, they won’t cut the forest,” he says. “The Udeghe won’t allow it. There would be a war.”

The villagers continue to fight the logging companies. Just last year, nearly the entire village traveled to Luchegorsk, the nearest significant town — a five-hour drive on dirt roads — to demonstrate against a proposal by a logging company to log part of the Bikin basin.

The demonstration, along with 25,000 signatures gathered by the World Wildlife Fund, convinced authorities in Moscow to kill the plan, says Yuri Darman, director of the Amur branch of WWF Russia.

“If there were no Udeghe people in Krasny Yar, all this country would be logged out,” Darman says.

FOREIGN GROUPS OFFER HELP

Efforts to save the Amur tiger from extinction have brought world attention to the Bikin basin. Environmental organizations and the German government have given grants to Community Tiger, the local group that controls the timber rights and hunting activities, to build an Udeghe museum and new housing for teachers.

Some of the money has been used to buy a billboard hung on the outside of the village school, showing a photo of a tiger and the words, “We save the tiger together!” There’s another poster inside the school, about the rarely seen Amur leopard.

During the village’s annual summer festival, a group of children repeat the slogan at the conclusion of a skit about a poacher killing a tiger and leaving its cubs motherless. Ihila, my daughter, plays the poacher. When she speaks her lines in Russian, the crowd applauds, recognizing her as the American girl who was also one of their own. Ihila is thrilled.

After the play, dancers wearing native costumes perform traditional dances, breathtaking in their athleticism and grace.

For Svetlana, this trip is about seeing classmates and relatives she hasn’t seen in 17 years. Her days here are filled with warm embraces and laughter. We can’t walk anywhere without someone running up and hugging her.

Would she want stay here rather than return to Maine? No, she says. Sure, life in America is easier, with indoor plumbing and big supermarkets. But it’s more than that. She likes the way Mainers treat her, with kindness and patience, and she feels secure and free in America.

When she is outside this river valley among ethnic Russians, she feels the weight of nationalism. She says many Russians look down on native people like her.

“I’m glad my children are growing up in Maine, so they don’t feel this,” she says.

Ihila, thankfully, doesn’t feel this weight.

Instead, during our walk in the forest, she is enchanted by this place, just as I was 20 years ago.

We wander back to the river and climb into her cousin’s boat. At one point, as we travel downriver, Gresha, Svetlana’s nephew, pulls to the bank and climbs out. He shows us a monument erected in memory of a friend who drowned in the river on this day two years ago. The body was never found. Gresha straightens up the site and places wild flowers on top.

When we get back to the village and pull ashore, we see a crowd gathered along the river. They are quiet, and formal, and I don’t understand what they are doing, until a little wooden raft drifts by us, carrying food and drink for their lost friend.

Once on shore, Ihila runs home to her mother to tell her all about our walk in the forest.

Tom Bell has worked at the Portland Press Herald as reporter since 1999. He lives in Yarmouth. He can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.