HALLOWELL – The folks who run the Harlow Gallery like to think big.

They do their share of small exhibitions that go up and come down, with little fanfare. But now and again, they do something way beyond expectation.

That’s the case with the gallery’s latest project, “CSA: Community Supporting Arts.”

During this year’s growing season, the gallery paired 14 artists with 13 Maine farms that practice Community Supported Agriculture. The artists visited the farms regularly, often getting elbow-deep dirty and helping with chores.

Based on those experiences, the artists produced a huge body of work, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, prints and videos. Some of that work is on view this month at the downtown Hallowell gallery.

This show has legs.

The volume of work was so large, the Harlow has arranged a series of seven exhibitions that will open across the region through the fall and winter. The project encompasses a geographic circle that begins in Hallowell in central Maine and extends north to Skowhegan, east to Belfast, south to Brunswick and west to Lisbon.

“Local food is one of my passions,” said Deborah Fahy, the gallery’s executive director. “I enjoy all the times I spend on farms and getting to know farmers and what their lives are like. We were looking for a big project, and this made sense.”

It fits perfectly within the mission of the nonprofit gallery, which involves connecting art and artists with their communities to bring about lasting social change.

The hope is that the exhibitions will bring attention to CSAs across central Maine, which in turn will raise awareness of and interest in the community farms as well as the artists themselves.

It’s a perfect exhibition for Maine, where art and agriculture naturally mix, said artist Christine Higgins of Readfield, who partnered with Annabessacook Farm in Winthrop.

As part of her work, Higgins made handmade paper using materials she collected at the farm, including corn stalks, cattails, garlic stems, meadow grass, collard greens and clay. With the paper, she made sculptural maps, among other things.

“Maine has a real strong regard for conserving the natural resources and for the use of the land. That is something I really responded to,” Higgins said. “I hope people who see these shows think more about the land and the use of the land — past, present and future.”

Especially in Maine, CSAs are a popular trend, following in line with the growth of the local food movement. CSAs offer consumers the chance to buy locally grown seasonal food directly from a farmer through a system of shares. In return for buying a share, the consumer receives a bounty of vegetables on a regular basis throughout the growing season.

It’s akin to a membership or subscription, and it’s a direct way for people to support community farms.

According to the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, Maine has more than 160 CSAs and more than 6,500 family investors.

ARTISTS CAME RUNNING

The Harlow Gallery secured about $16,000 in grant money for the project. Among the funders were the Maine Community Foundation, the Davis Family Foundation and the Maine Arts Commission.

When it announced a call for artists, the gallery was overwhelmed by the response, said Chris Cart, who helped organize the show.

“We had to turn away a lot of good artists,” Cart said. “We did not want just a painting show or just a sculpture show. We were looking for artists who would provide a real textural mix.”

Tyler Gulden of South Bristol made clay pots based on his experience at Morning Dew Farm in Newcastle. Gulden is executive director of the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Newcastle, which borders the farm. He and his family are members of Morning Dew’s CSA, and the farm supplies Watershed with food, as it does several local and regional restaurants and markets.

Gulden worked at the farm over several months, helping to bunch scallions and herbs and cutting fennel, among other chores. He arrived in the spring when seedlings were fledgling in the greenhouse and followed the season all the way through to harvest.

“You name it, I was helping out in the field. That was an important part of the process for me, to get a sense of the scale of the operation and work it takes to get things out of the land,” he said.

In response to that grand scale, Gulden found himself making much larger clay pots than he is accustomed to making.

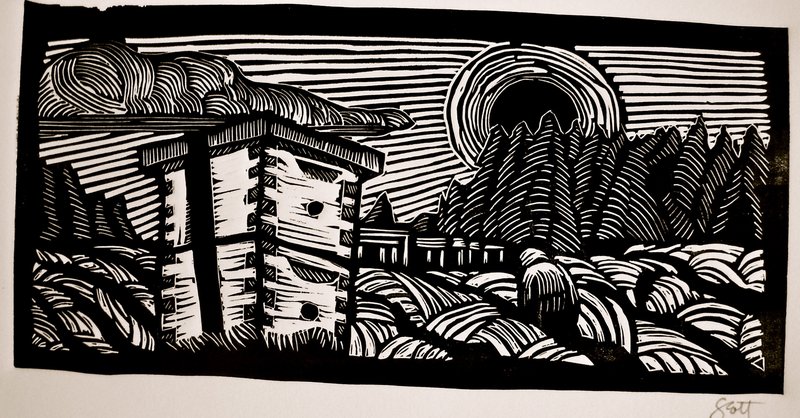

Scott Minzy of Pittson made a series of prints based on his experiences at Long Meadow Farm in West Gardiner. He is best known for dark-themed illustrative work. Hanging out at the farm brightened his work considerably. He made many happy images of sunshine scenes and farm animals.

Being on the farm was a new experience for Minzy. “I am a child of the ’80s,” he said. “I grew up on video games and comic books.”

He found himself going back to art-school lessons, and responded to things he saw as opposed to things he imagined, as is his typical studio practice.

“I ended up responding to the environment,” he said. “In my regular work, I do the opposite. It’s nice to have direct contact with things that are in front of you. It was fun to get lost staring at tomatoes.”

His impression of the farm?

“Just how incredibly hard these people work. I would go for a couple of hours and draw, or sit and listen to their conversations. But they are up at sunrise and are at work, and they don’t come home until long after 5.”

SERIOUS BUSINESS

Aleana Chaplin of Gardiner, a sculptor, had a similar experience at her farm, Winterberry Farm in Belgrade.

“They are the hardest-working people I have ever met. Everyone on the farm has a job, and they all take that job seriously,” she said.

For her, this project was about reclaiming the integrity of the land and taking responsibility as a community to “take care of our farmers, because they take care of us. … I’m a huge advocate for learning to care for the land.”

Brady Hatch, who runs Morning Dew Farm in Newcastle with her husband, Brendan McQuillen, hopes this project highlights the fertile community of Maine, both artistically and agriculturally.

Hatch grew up on the property she now farms. Like many Maine-born teenagers, she moved away at first opportunity.

“After I left, I realized what I really wanted was to do work outside and do something that made a difference in my community,” she said. “When I looked back on Maine, I realized that this is my community.”

She came home and learned to farm, and now feels an integral part of her community.

Hatch loves this blending of arts and agriculture.

“Each farm is as individual as a work of art,” she said. “You have different material to work both in geography and the market and the crops you are good at growing and able to sell. Using the farm as a stepping-off point for inspiration makes sense to me.

“There is lots of beauty to be found here.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story