Dana Sawyer first fell in love with the story of “The Radiant Deer” years ago, on one of his many trips doing academic research in India. He brought an English translation of the Buddhist children’s tale home to his own two young daughters, and they fell in love with it too.

Sawyer’s children are now grown, but with the publication of his new book, he has made sure other Maine children will have the chance to read the story of the compassionate deer who saves a snake charmer’s life.

“The Radiant Deer” is one of the Jataka Tales that convey simple Buddhist teachings by telling stories of the Buddha’s previous births in various animal forms. Sawyer has done his own translation of the story from Hindi into English. A collaborator, Pema Tsewang, has translated the story into the Tibetan language.

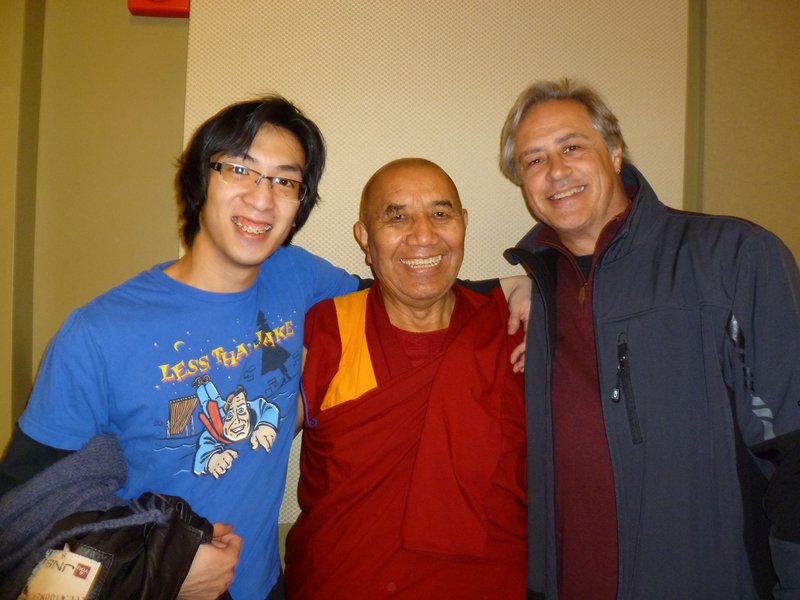

All three versions of the story — Hindi, English and Tibetan — are printed in “The Radiant Deer” (J.S. McCarthy, $15). Pin-Wei Chiang, a recent graduate of Maine College of Art, provided the illustrations. All the proceeds from the book will go to the Siddhartha School in Ladakh, India, which was founded in 1995 by Khen Rinpoche Lobzang Tsetan, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and educator.

Sawyer, 61, is a professor and chair of the liberal arts program at the Maine College of Art, where he teaches courses in philosophy and world religions, particularly Asian religions. He is the author of a biography of Aldous Huxley, and is currently working on the authorized biography of Huston Smith.

Sawyer lives with his wife, jeweler Stephani Briggs, on Portland’s West End.

Q: Tell me about the school that will benefit from this book.

A: The Siddhartha School (siddharthaschool.org) started in 1995, and the real impetus for it was that Khen Rinpoche was concerned that so many children in Ladakh, his home region, were failing the college entrance exam. In fact, 90 percent of all Ladakhi 10th graders were failing the college entrance exam for India.

And the reason for that is they’re kind of an afterthought. They’re way up in the snowy region of the Himalayas. Ladakh is about the size of Ohio, but it only has two roads that come into it, and they’re both clogged with snow except for four months a year. So it’s very difficult to get to. There’s only one airport in the whole area.

Ladakh is part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which is a Muslim state, and of course the state government doesn’t really care much about these Buddhists living up in the high Himalayas. They come at the end of the bread line when it comes to financing. And because they’re Buddhists in a predominantly Hindu nation, they’re really an afterthought on that level too.

None of the schools were teaching in their own language of Ladakhi, which is a dialect of Tibetan, so the children had to immediately get on this horse of learning Hindi, and then in middle school learning English, and being able to study in those mediums, and they couldn’t. They were behind the curve, and so they were all flunking the college entrance exam.

So Khen Rinpoche said, “What if we had our own school, and children could begin their education in Ladakhi, then they would come up to speed in a way that they would be able to perform more successfully?” And the fact of the matter is, we’ve had three graduating classes now. Every one of our students has passed the college entrance exam, and year before last, a girl in that graduating class set the state record for all of Jammu and Kashmir, which includes some very large cities. She set the state record for performance on the college entrance exam.

So it’s been successful. He had a really brilliant idea, and now we’re up to 320 students. In fact, one of the challenges we face right now is that because of the school’s success, more and more people want to come. … Rather than turning them away, he’s trying to grow the school bigger.

Q: Haven’t Mainers contributed to this school before? Is there some sort of tie there?

A: There’s a deep tie. That’s what’s really amazing about all this. (Khen Rinpoche) was in a Tibetan learning center down in New Jersey for a few years. When he started the school, there was a bookstore up on Munjoy Hill called “Maybe Someday.” The woman who operated that had a connection with him somehow, and she brought him to Portland.

And then he met a few people up here, and as he would come to Portland and give introductory lessons on Tibetan Buddhism, mostly as a way to raise money for the school. There were people that were attracted to the Buddhism, but there were even more people that were attracted to this idea of helping underprivileged children in the Third World. There was something about that message and his commitment to his home village of Stok — where he built the school and where he himself grew up — that really resonated.

I call it the Down East/Far East connection. I don’t know why people embraced it with such exuberance, but they really did. Even to this day, the lion’s share of the funds that come in to support the school are coming primarily from Maine.

Q: What are the Jataka Tales? Are these stories that the children in this school would have grown up with?

A: Definitely. “Jata” means “birth,” and so the idea is that before the Buddha had his lifetime as Siddhartha Gautama and reached enlightenment, he had been incarnated many times. And so these are stories of his earlier births, not only as a person but as a monkey and a deer and a whole host of animals… in fact, there are more than 500 Jataka tales in all.

Q: What lessons will children learn from “The Radiant Deer?”

A: There’s a few there. One is most definitely to be careful about how greed can steal your own mental peace. You want something so badly, like the queen wanted the hide of the radiant deer, that it had really thrown her off balance. It was disturbing her relationship with her husband. It was disturbing people in the kingdom, and it was pushing them in the direction of doing something ignoble.

Then there’s the piece about going back on your promises, breaking loyalty. After the deer saves the life of the snake charmer, the deer knows that there would be people who would want to have his pelt, and so he asks the snake charmer to promise to never tell anybody that he met the radiant deer. And even though the deer had saved his life, (the snake charmer) breaks that promise, because he too is greedy and wants the bounty that the queen has put out on the hide. So there’s pieces about breaking trust and maintaining loyalty and being wary of greed and too much desire.

And then, you know, compassion. What motivates the deer to come and help the snake charmer in the first place? Why would he jump into a rushing river to save someone he doesn’t even know? And that’s the compassion for others that is so endemic to Tibetan Buddhism. There’s a part in there where there’s a deer and a squirrel that are being overcome by snow and cold, and the deer lays down beside them and lets his body warmth warm them back up. And so whenever we see the deer, he’s always interested in other beings. He finds his happiness through helping others.

Q: You gave versions of these stories to your own daughters when they were little. Did you find it helped you as a parent to discuss these issues with them?

A: Definitely. Definitely, definitely, definitely. Because little children don’t have the development of the rational mind to the point where you can give them a logical, rational explanation for why they should be compassionate or why they should be loyal. You know, if you’re going to talk to a child about why they shouldn’t lie, you’re going to get a lot further with the Pinocchio story than you are with a kind of junk in, junk out computer analogy.

Little kids aren’t equipped to understand those things, but when you read them a story, they have a natural resonance with a character like the radiant deer and they see, “Oh boy, I admire him so much because he’s so nice to others.” Then you find your kids playing well together after you read the story, giving each other a little more leeway and not being so me, me, me.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.