One distinction we don’t make often enough is between the roles played by brushwork and paint itself. There is a graphic quality to Maine painting in general that is tied to the high esteem we put on mark-making and brushwork.

But brushwork bravado isn’t the only thing you can appreciate. Sometimes, artists indulge in the qualities of the paint itself. This is easier and more poignant in settings where the artist’s relationship to paint (rather than the landscape) is what drives him — think of New York and its storied relationship to painting.

I was struck by how Jonathan Blatchford and Shirah Neumann, both of whom are featured at Aucocisco Galleries in Portland, are deeply enamored with paint — not their own brilliance with a brush, but the paint itself. They treat it like some magical substance worthy of awed honor.

Which, of course, it is.

One of the standbys of the New York school of painting is a loaded, very wet brush. We see this rarely in Maine, because our tradition is tied to a plein air practice that values efficiency and requires a smaller, more portable palette. Large jars of liquid oil paint are the stuff of studio practice, not the field.

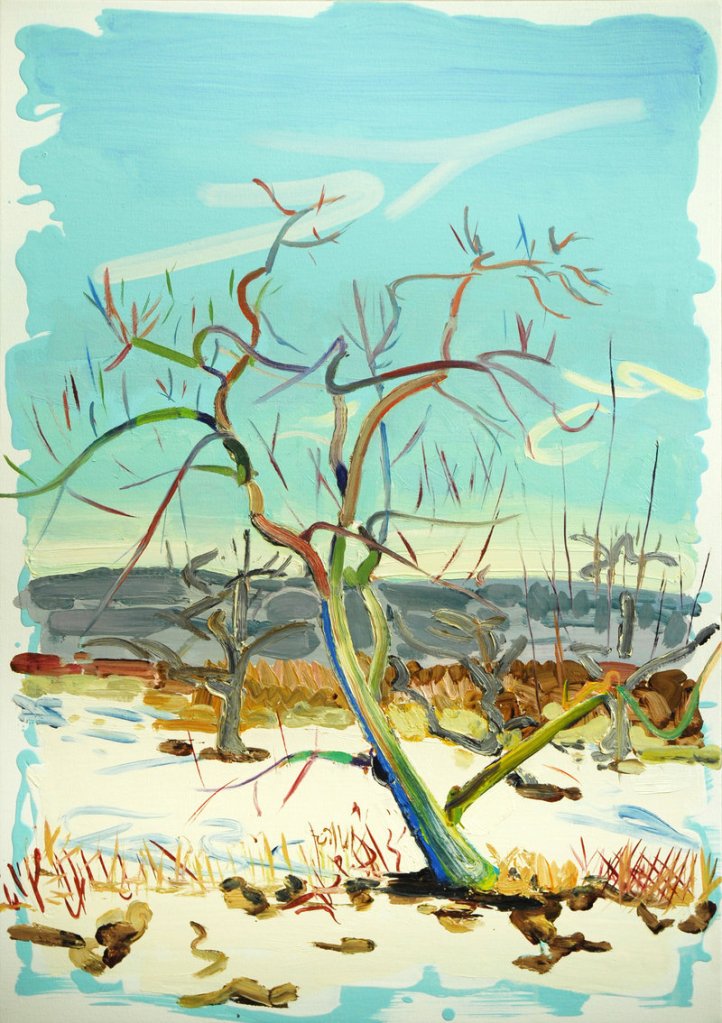

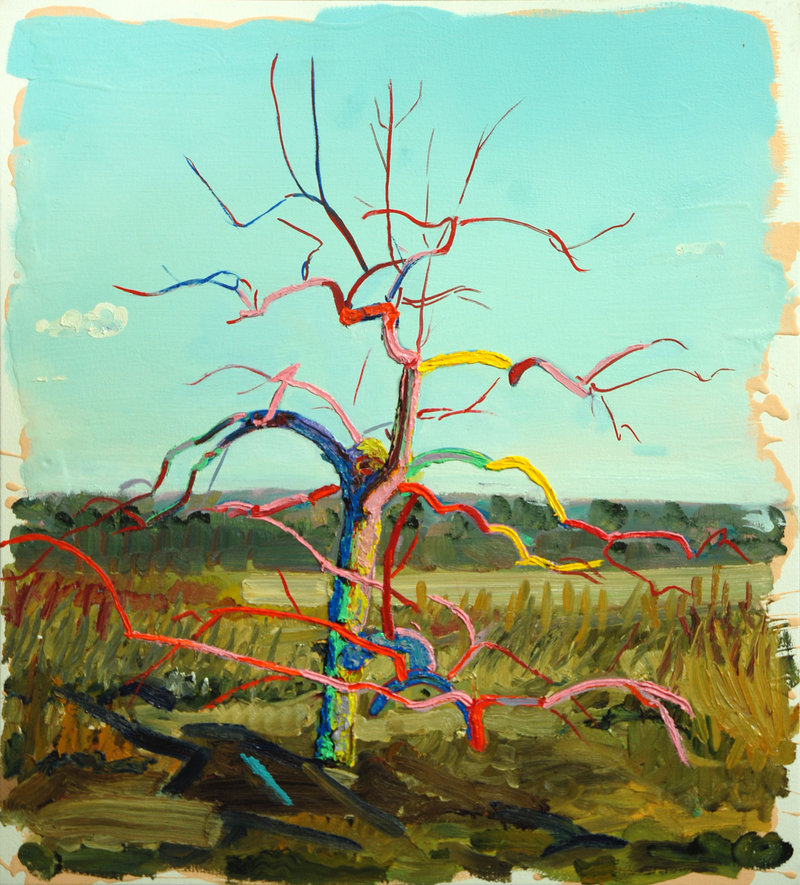

We see these squishy liquid marks in Blatchford’s orchard paintings, particularly the writhing rhythms of the snaking green and ochre ground of “Orchard #15.”

Like all six of Blatchford’s canvases, “#15” features a single, leafless apple tree in an orchard under a cold blue sky. The background paint revels in liquid logic, and the trees gather substance by being sculpted up from the ground with solid paint — with a look like the full-bright colors were squeezed directly from the tube onto the surface. Blatchford keeps the solid colors from flattening by using many different and heavily-saturated pigments: Yellows, reds, greens, pinks, blues and so on.

In other words, he is painting with color, not light. This makes the visual motion and dynamism of his work based in perception rather than description.

Oil paint is rich enough when liquefied by medium to travel quite a distance around a canvas, but many artists lay down a bunch of paint and then push that around with their brush. It’s clear that Blatchford has a thing for liquid paint. In his “Orchard #4,” for example, you can easily see the folds of the paint as he laid it on (while flat) with a large brush. It’s an indulgent favor to the viewer that he leaves a margin from the edge of the white canvas; it’s a beautiful thing if you like paint (which I do).

In this case as well, Blatchford moves between the margin and the snowy ground with a positive/negative play that tips its hat (with a wink and a nod) to the push/pull of the old-school American abstraction championed by Hans Hoffmann.

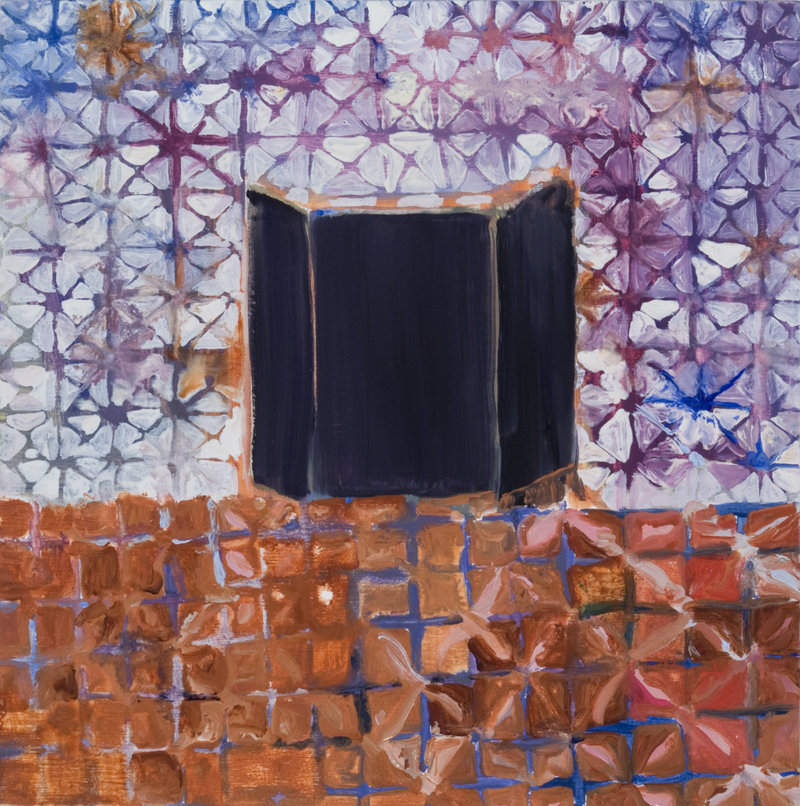

Neumann’s work has a much broader range of content, but shares Blatchford’s positioning paint as a semi-magical substance. Her paintings tend towards patterns and special forms with the project of looking to art history for lessons from others who have shared her fascinations. She makes direct and indirect references to artists such as Johannes Itten, Philip Guston, Arthur Dove and then even Arabic miniature painting and its echoes in Les Nabis and more recent contemporary process painting.

Neumann’s “Circuit” is a particular favorite. It features a largely black-and-white palette showing a circuit system of clouds above a pair of pointy mountains (which protect a magic cupcake between them).

While it’s a bit too much of an illustration of a hifalutin’ philosophical quote (Deleuze on painting as a time system), its genuinely fun gestures toward Guston and Peter Halley allow this to be a very successful painting.

Many of Neumann’s paintings combine flat-screen forms (think Arab miniature and/or old Maine radiator covers) with an odd rectangular form that clearly has special significance to the artist, like some form of visual mantra. Rather than appearing as an indecipherable rebus, it takes the form of a personal, mystical device; less anchor than launching point, it plays the part of fulcrum in many of her paintings.

Neumann’s paintings are bold, and manifest an unusually original sensibility. She loves paint, but she isn’t a slave to it. She is willing to be very ugly sometimes to achieve painterly points about color, such as her oddly compelling “Red Sky,” with its black pyramid and bile-green ground under a popping scarlet sky.

Her strongest works ride centered structures of triangles and lozenge forms, such as her large triple-mountain “Diamond Sky” and vertical “Double Barn,” the latter with its purple interference palette chiseled like staring straight up the corner of a large, geometrical building (with that “Vision Sight” form once again dropped into the center).

Neumann’s most appealing piece is her “Old Man of the Midnight Sea” — a large, blue seascape with a 12-point geometrical form at the bottom, stiffly stylized trees and a swarming sea all around. It’s like the sparkling rhythms of a choppy ocean rendered in a chromatic scale; like maybe if Claude Debussy got a little less romantic and a lot more funky.

This is an extremely enjoyable and interesting exhibition, but most exciting is the promise of two bold young painters.

They are two to watch.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.