Print shows, for some reason, are dotting the Maine landscape.

No one has been more active in mounting print shows recently than Bruce Brown, curator emeritus of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art. His “Prints: Breaking Boundaries” at the Portland Public Library is a good show. But it’s also an important show, although a casual visit might not reveal why.

“Breaking Boundaries” is wildly diverse, and you might take this either way on first glance: You might think it lacks a compelling unifying theme, or you might get the idea that Maine has a ranging and highly energized printmaking culture.

Both are correct.

But honest survey exhibits seek disparate range, and if Brown has anything to offer, it’s range.

“Breaking Boundaries,” sponsored by the CMCA, is a lousy title, because it brings to mind iconoclastically anti-establishment energies, and that’s not what’s bubbling in the conceptual undercurrents. These works use the professional tactics and techniques of printmaking to reach across boundaries to conceptually common ground.

Few pieces stand out as you enter. You first see Ellen Roberts’ giant “Light,” which you might think is a banner sign, then Kristin Fitzpatrick’s “Roof,” a hanging rooftop form that is weak from above but comes alive architecturally when you look up through the backlit woodcut “shingles.” I don’t like it, but it’s a revealing piece.

“High Chair” by Fitzpatrick’s fellow MECA undergrad, David Twiss, is genuinely striking. With its incumbent black bib (very goth) and shaped chair back covered with an image of a rather vicious wolf, it’s not for every baby. It is Gorey-dark and hilarious.

The work of Tanner Gasco-Wiggin impressed me. It’s an Oak Street scene in spray paint and orange cheesecloth pretending to be a farm barn and silo. It’s smart, sharp and conceptually restive.

This raises questions: Are students focusing on printmaking because they get lots of art from one matrix? Do they leave printmaking after school because it is cost-prohibitive? Or are they drawn to current conceptual ideas analogous to a post-digital digestion of Walter Benjamin’s “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”?

I am inclined to think it’s all of these and more. Specifically, I think the professional/technical qualities of printmaking make it the logical medium for the process/finish-oriented conceptualism we’re seeing throughout Maine. Prints also stem from the intellectual epicenter of the post-Warhol, digital, Etsy-market style of the art world in which younger artists have grown up. The original and its aura, after all, are dissolved by iTunes, digital printing and the Internet.

While photography is suffering a digitally-inspired existential crisis, printmaking is enjoying a golden moment. Artists across mediums are being drawn to technical processes such as encaustic painting, wet-plate photography, glass blowing and printmaking.

Since the Internet became ubiquitous, fine print markets — unlike photography — have been professionally solid. This only increases the appeal of artists who then make unique interventions with the prints.

That is where “Breaking Boundaries” offers particularly interesting insights. Some artists, such as Elizabeth Jabar and Holly Berry, accessorize their works into sculpture (Berry’s fold-out visual recipe book for squash soup is wonderful).

Shawn Brewer’s classical architectural fantasy objects can be cut out and assembled (a before/after pair is on view), yet their brilliance is in the subtle dare: Could you take scissors to an etching?

I adore Meg Brown Payson’s large (15 feet), subtle and quietly gorgeous “Silkwall” — a lithograph/drawing hybrid that mobilizes the texture aesthetics of a biologically microscopic world to challenge abstract painting. The transparent silk floats 4 inches above the wall on which Payson has drawn similar images so that — with feints and wit — they echo each other.

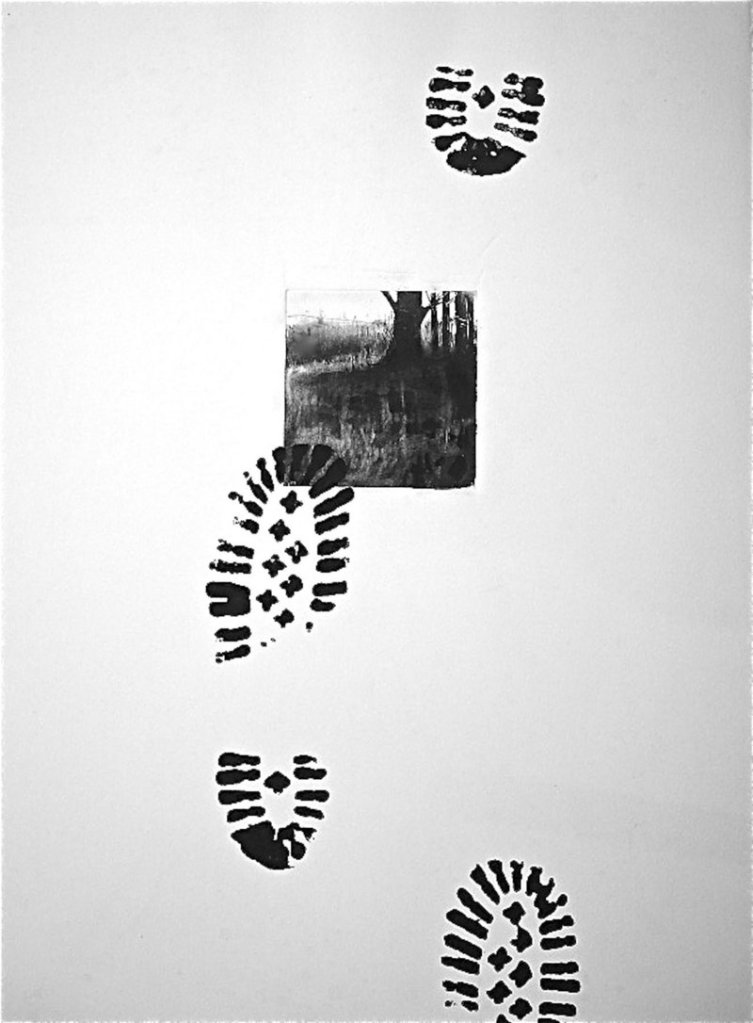

I hardly have the space to list all my favorites, let alone discuss them, but highlights include our beloved Will Barnet’s elegant “Interlude,” Tom Hall’s smartly boot-stomped landscape “John Muir once said,” Henry Wolyniec’s serious but dance-jumpy retro abstraction “HW12.25,” Adriane Herman’s symmetrically hilarious travel-spill luggage disaster “You Lose, You Ooze” and Karen Adrienne’s elegantly messaged and politically unfurled abstraction “For the Two: Question #1.”

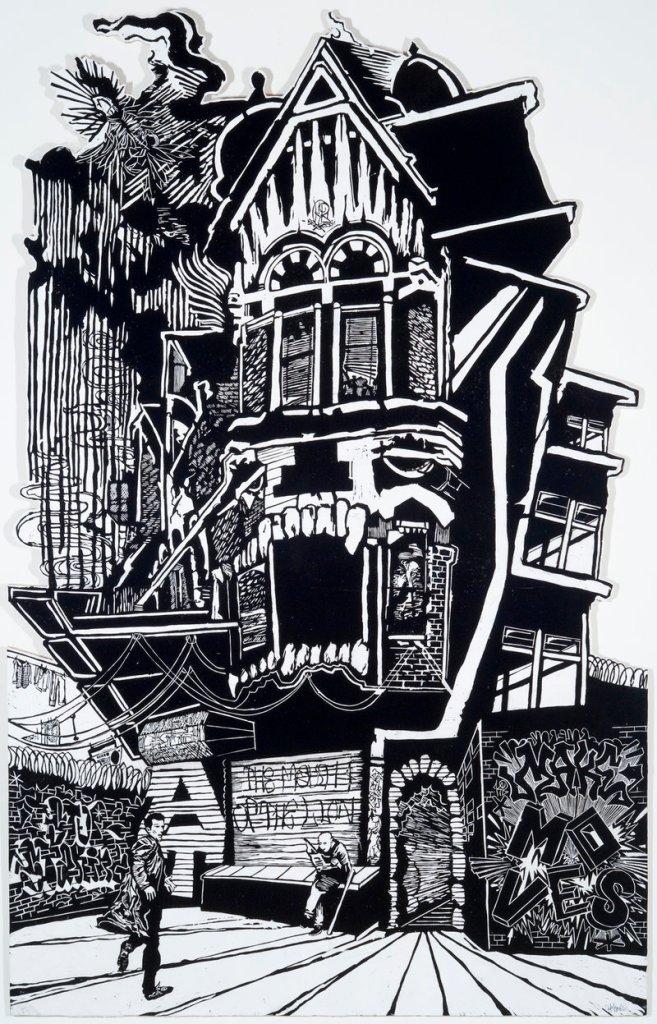

The most insightful, complex and important piece is Kyle Bryant’s large woodblock mounted on shaped wood, “The Mouth of the Lion.” Bryant reaches uncomfortably but agilely from giant-scale woodblock through art history directly into street art. The black-ink scene shows an urban house as a monster face: A terrifyingly overlooked reservoir of revolutionary energy.

The building is self-titled and graffiti-tagged, including Bryant’s own signature as the house monster’s ironically omniscient third eye.

Bryant is not only navigating art history within the image, but he is engaging — and conceptually surpassing — overrated but important artists like Swoon who have made the guerrilla-style wheatpaste art movement into a genuine cultural force.

Bryant’s work is tough, and he is one to watch.

Walter Benjamin’s groundbreaking 1936 “Work of Art” essay assumes a worthy original work of art whose meaning and aura could be crushed by the weight of its reproductions. But Warhol showed us those reproductions could create overwhelming cultural power that, until he came along, had not been mobilized in fine art.

With process and conceptual art, the Internet, water-based inks, Etsy, digital printing and photography all at their fingertips, artists now have a bag of tricks unlike any other in history. They aren’t caught up, like most of us always have been, in artifacts.

“Breaking Boundaries” may seem to jump all over the place, but if you take some time with an open mind, you can glimpse some of the edgiest questions in American art.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story