Back in November, my 22-year-old friend Patrick Cochran mentioned in passing that he wanted an old typewriter for Christmas.

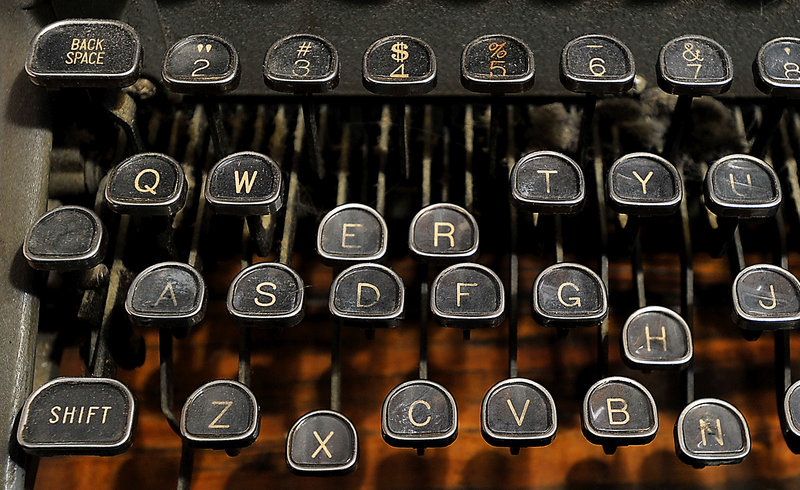

As is the case with most people his age, this kid — as a 50-year-old, I can call him a kid — had never used a typewriter before. He’s an aspiring journalist, and his career as a college scribe has consisted of writing on a laptop. Never once had he experienced the clumsy joy of a manual typewriter, with its stiff keys, snarled ribbons and clackety-clack cadence.

Until Christmas morning.

Under the tree sat a dead-weight circa 1940 Woodstock typewriter. It was big, black and beautiful.

At first, he just looked at it, unsure what to do with it, or how. With visions of Kerouac dancing in his head, my young friend hoisted it up with both hands tucked under its sides and plunked it on the table.

The way he considered it was not unlike a puppy learning how to descend a flight of stairs the first time: Timidly. He looked it over, leaning in to get close to the keys and trying to figure out exactly how to proceed.

I wondered if he was looking for the power button or charging port. Then I realized he probably had never loaded a piece of paper in the roller, never swung a carriage return bar, never released the tension on the carriage to align the paper.

My friend, who has since mastered the bulky old albatross and now keeps the neighbors awake with his midnight writing, is part of a growing renaissance that is returning the manual typewriter to royal stature. Just as vinyl records are finding fans among those who grew up in the digital age, the manual typewriter is finding a small but devout niche among subculture revivalists.

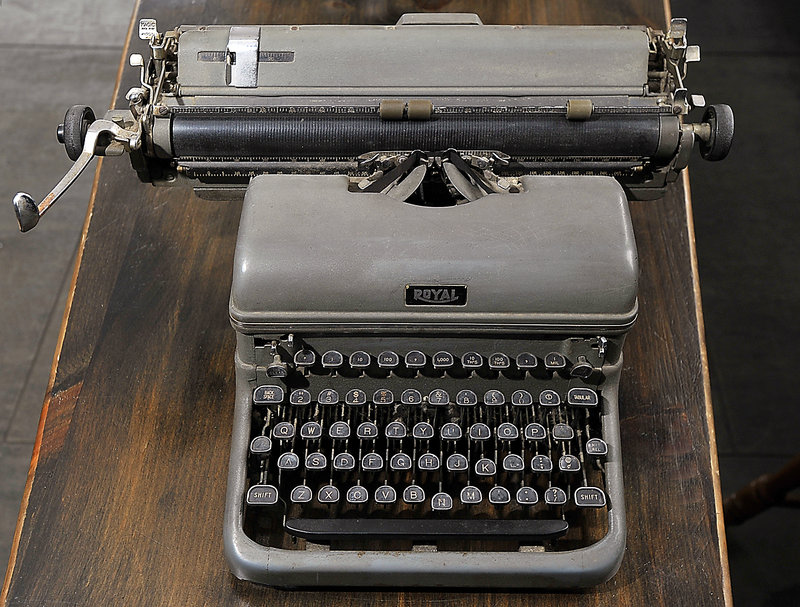

Patrick Costigan of Cosco Technologies in Winthrop has experienced the revival first-hand. He specializes in business machine sales and service. Increasingly, he is being asked to fix and refurbish manual typewriters.

“I get them from all over,” he told me after I dropped off my old typewriter for service before giving it as a Christmas present.

For my young friend, the whole thing was a mystery, the stuff of legends and lore. His favorite writers created their best work on these things, and he was in awe.

He appeared nervous before he began his virginal typewriter experience. Slowly and with obvious uncertainty, he began pecking, one key at a time. The shift bar startled him — the whole carriage moved when he chose a capital letter.

He noted the lack of “1.” I explained that he had to use a capital “I” for the number one, and warned that he would soon discover other “missing” keys.

NEW LIFE FOR AN OLD DOG

The typewriter came to me as a gift many years ago. A journalist friend who was moving on from my former newspaper opted not to lug it back across the country, and offered it to me as a token of our friendship. I used it as a display piece in my home office for a good 20 years. It seemed fitting to pass it along to another journalist, to keep the chain going.

I never used it for writing. Instead, I wore out a series of word processors, desktops and laptops. Meanwhile, the old typewriter stood by, collecting dust.

Costigan told me it was in excellent shape. He documented its genealogy to at least 1940, and based on the serial number, he thinks it might date to 1938 or earlier. After Costigan replaced the ribbon, oiled the moving parts and attended to a few other details, the machine sang.

Costigan demonstrated its nimbleness as he sat at the keyboard and banged out a few lines.

Each time he reached the end of a line — ding — he hit the carriage return, advancing the paper and zipping the roller, or platen, back into its starting place. The mechanical sounds were musical, reminiscent of snare drums, cymbals and the Cajun washboard.

Costigan has a long history with typewriters. His father, Ronald, serviced typewriters in World War II, and later got into sales for Underwood, which produced the most popular typewriter in the country in the first half of the 20th century.

Olivetti took over the company in the 1960s, and Costigan’s dad kept selling. In 1969, according to his son, Ronald Costigan was the top salesman for Olivetti in the country, working out of Augusta.

“He had that Irish personality. He could tell a story and he could sell anything,” Costigan said. “People loved him.”

When his father retired in the 1980s, Costigan and his brother took over the business. As things happen, times and technology gutted the typewriter business. The Costigans adapted, moving from typewriters to fax machines to printers.

But he never let go of the typewriter business altogether. These days, he thinks he’s the only guy in Maine who services manual typewriters, operating out of a small office attached to his home. A framed picture of his father hangs on the wall, linking the family forever to its proud history with the typewriter.

Costigan will tell you that the typewriter never went away entirely. It’s still a functional, efficient and frustration-free machine for writing on index cards, labels and envelopes. Many offices still have a machine under a dust cover somewhere in the corner.

And now they’re coming back — in a limited and almost entirely nostalgic way.

“It’s never going to be like it used to be. They’re not coming back like that. But there is interest. And I can see why. When you look at that machine,” he said, gesturing to my beautiful Woodstock, “it’s a great piece of machinery. It’s incredibly well made.”

And durable. Some 70-plus years after its manufacture, my typewriter is still functioning.

CONNECTING WITH WORDS

My friend grew up in a digital age, and is as connected as anyone. For him, the typewriter represents a way to step free from the tethers of technology and connect more with the words as they form in his head and then are transferred to the page.

He feels more in touch with his thoughts when he writes on the typewriter, and perhaps less distracted. It hasn’t changed as much how he writes as how he thinks.

He’s not alone.

“Lots of friends and people my age are into the idea of writing on a typewriter, for similar reasons,” Patrick wrote in an email, which he composed on his laptop.

“I don’t think anyone really thinks of a computer as a tool for writing, and that’s maybe where the appeal comes from. For some modern writers, I feel like the typewriter is still that unique tool that kind of belongs to us. Painters still have brushes, musicians have instruments, and I think maybe a lot of us just like the idea of an instrument just for writing.

“I do know a bunch of people, friends that aren’t particularly into the idea of writing, who can’t understand the purpose of using outdated technology. I don’t think of myself as rejecting technology — I use a computer daily and am an active member of numerous branches of the social media. I just like the idea of writing with the instant access and connection to what I write.”

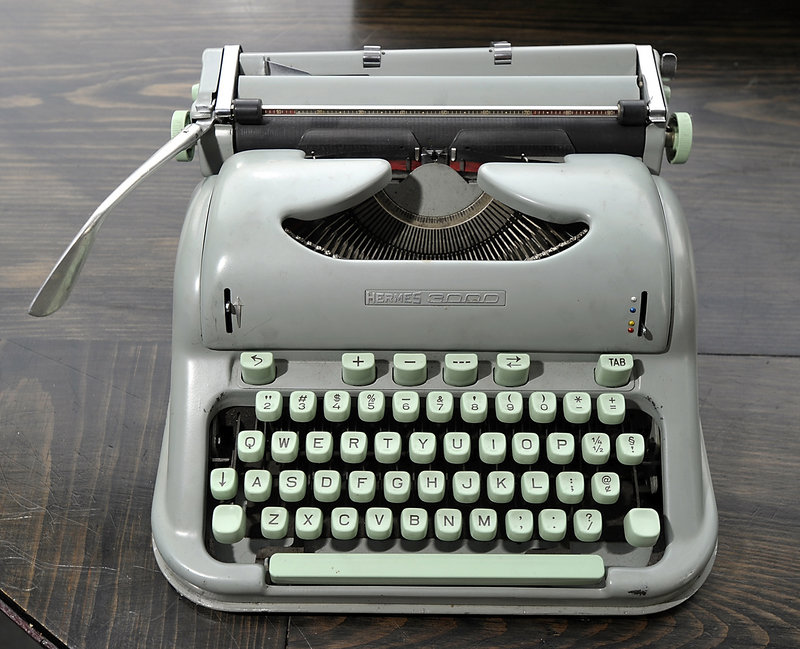

Tom Furrier of Cambridge Typewriter Co. in Cambridge, Mass., has witnessed this trend first-hand. About a decade ago, a couple of teenagers came into his shop to gawk at manual typewriters. A week later, a few more came in. And then more and more and more.

It has since snowballed to the point that he can barely keep up with the crush of people wanting to have their old typewriters fixed and made serviceable.

“The majority are high-school and college kids. They’re looking to offset the digital side of their life,” said Furrier. “They like the idea of having something analog, something mechanical.

“School kids have never played with anything like this before. They’re used to keyboards, gaming consoles and laptops. The typewriter is pretty cool to them. You press a key, and this permanent impression appears on the paper in front of you. They love the feel and the sound and the looks. They’re totally captivated by it.”

TYPISTS WELCOME HERE

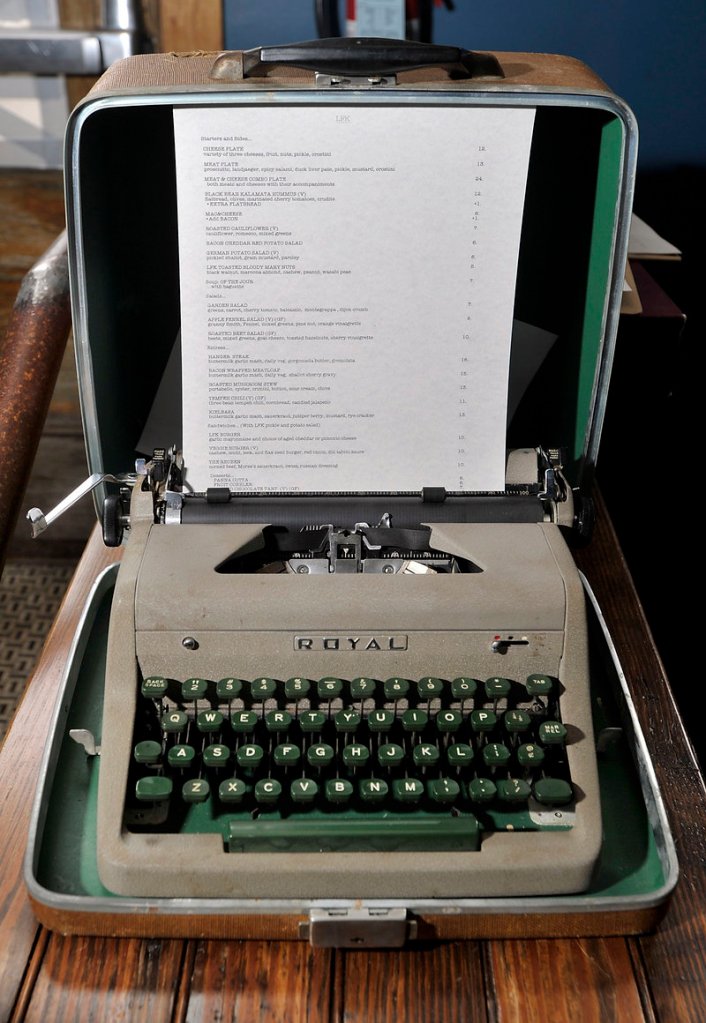

LFK, a tapas bar at 188A State St., Portland, serves as a haunt for the typist clan. Owner John Welliver designed LFK with words in mind.

The bar itself is shaped to resemble a typewriter, and is embedded with keys manufactured to look like typewriter keys. (It’s important to note that these are not actual typewriter keys. In the typewriter world, it’s considered bad form to remove keys from the typewriter, and Welliver had no desire to disrespect the typewriter community when he built the bar.)

If you look closely, you will see that the keys spell out the words to Emily Dickinson’s poem “After a Great Pain, A Formal Feeling Comes.”

The bar includes many typewriters, which patrons are encouraged to use. Books are also scattered about, most from Welliver’s private collection.

Welliver, who works as an editor for a literary journal, says the typewriter revival fits nicely into a larger societal trend that finds people returning to simpler, less complicated things, if only for tactile pleasures.

There’s resonance in the sound of the keys smacking up against a piece of paper that is lacking on a modern keyboard, Welliver says.

“When you work in the literary world, there is some sort of longing for history, to feel like you are part of a guild that has lasted centuries, since typewriters and the printing press and things of that nature were invented,” he said. “It makes you feel like your job is worth it.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.