When it comes to Maine’s Civil War regiments, not all have gotten their fair share of publicity.

The 20th Maine is the one everyone knows about. It was commanded by Col. Joshua Chamberlain at the pivotal battle of Gettysburg and brought to life in a 1993 movie about the battle.

But folks who know will tell you that another group of Mainers at Gettysburg — the 16th Maine — has a story that’s also worthy of a cinematic retelling.

“It was the first day of the battle, and the Union forces were retreating up the hillside as thousands of Confederates were pouring into the area,” said Maine state archivist David Cheever. “So the Union command needed someone to hold back the Confederates just long enough while they retreated.

“The 16th Maine, with under 300 men, was pressed into service. Without the sacrifice of those men, the 20th Maine never gets to be the 20th Maine.”

The story of what the 16th Maine did and how it likely helped the Union avert defeat has finally made its way onto film.

The 30-minute documentary “Sixteenth Maine at Gettysburg” is a collaboration between the Maine Public Broadcasting Network and the Maine State Archives. It will premiere on MPBN television stations at 9 p.m. Monday, the 150th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg.

The film draws on Civil War records and writings from Maine’s soldiers contained in the state archives, which are used in the narration, as well as historic photographs, new footage shot at Gettysburg and re-enactments shot in various locations.

Cheever had approached MPBN with the idea of telling the stories of other Maine regiments that fought at Gettysburg, and the story of the 16th caught the network’s attention.

“It’s one of those untold stories that is very compelling” said Dan Lambert of MPBN, who directed the documentary. “The 20th Maine’s story has been well told, but that was the second day. This was the first day.”

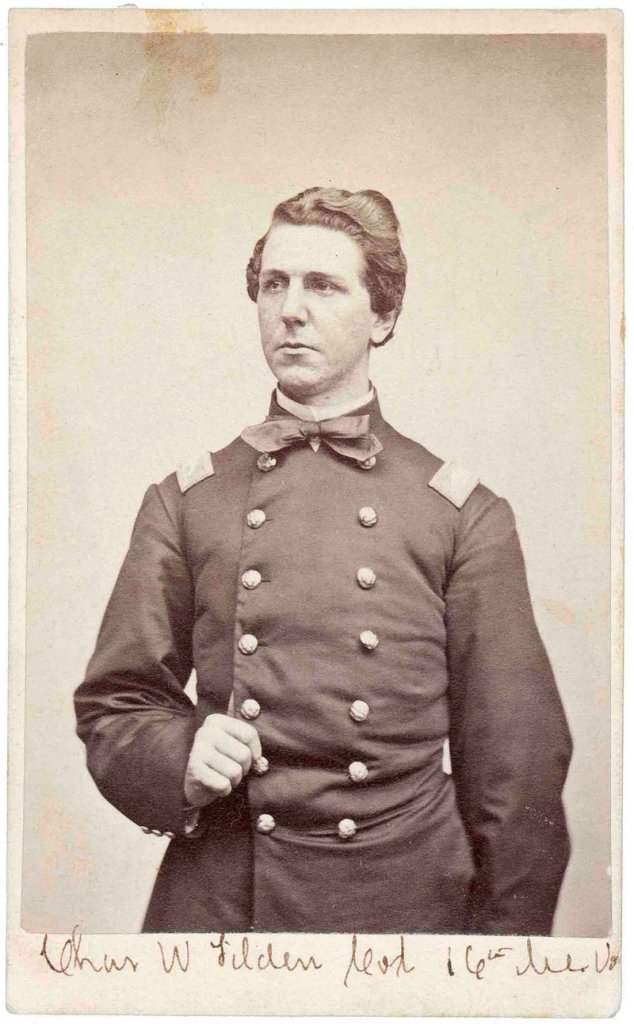

Under the command of Col. Charles W. Tilden of Castine, the men of the 16th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment had been marching since the middle of June, chasing Robert E. Lee’s troops, when they arrived at Gettysburg, Cheever said. The regiment had been called “The Blanket Brigade” because of an earlier battle in the war when it had been ordered to leave an encampment without overcoats, knapsacks or tents as Lee invaded. The men were often seen afterward marching in rain, snow and sleet with their blankets wrapped about them.

At the battle of Fredericksburg in late 1862, the regiment lost 250 men killed or wounded, yet took 200 prisoners and “would have gone on to the rebels’ second line of battle if they had been allowed to do so,” wrote Lt. Francis Wiggin, an officer in the regiment.

So on July 1, 1863, the regiment was down to 275 men when it joined the first day of battle already in progress at Gettysburg. When Union commanders realized they needed to retreat to Cemetery Ridge if they had any hope of winning, Gen. John C. Robinson ordered the 16th Maine to position itself as a rear guard to slow the Confederate advance.

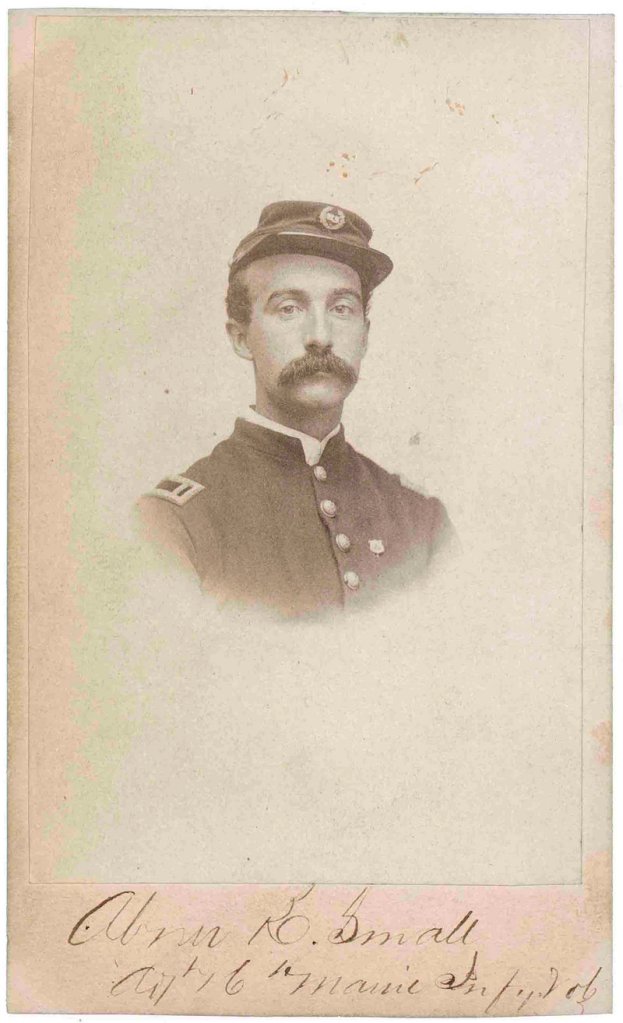

“We were sacrificed to steady the retreat,” Abner Small of Waterville, who was the regiment’s adjutant, wrote in his memoir.

Small and others wrote after the battle that members of the 16th Maine realized they’d surely be killed or captured, and that, in Cheever’s words, “the war for them was going to end in about half an hour.”

Still, they decided they would not give the Confederates any symbolic spoils of battle. They tore the regiment’s colors to shreds and divided up the scraps among the men so the flags could not be reassembled.

“We looked at the colors, and our faces burned,” Small wrote. “We must not surrender those symbols of our pride and our faith.”

Cheever said Tilden also snapped off the handle of his sabre so it could not be surrendered.

Exactly how long the 16th Maine, armed with muskets, held out against thousands of Confederate troops is hard to say, Cheever said. But it was long enough to allow the Union forces to regroup and get ready for the rest of the battle.

The Union’s victory at Gettysburg is regarded as a turning point in the war. The Confederate army never recovered from the loss.

Eleven members of the 16th Maine were killed during their stand, 59 were wounded, and 164 were taken prisoner, including Tilden. About 30 men, including Small, escaped and rejoined the Union forces.

“They bought just enough time to let the rest of the Union Army get a superior defensive position,” Cheever said.

Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.