The current five-person show at A Fine Thing: Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts is a great reminder that gallery directors are some of Maine’s art assets. Pollack has assembled a show of artists whose work reflects back on each other in such a way that elevates all of the work.

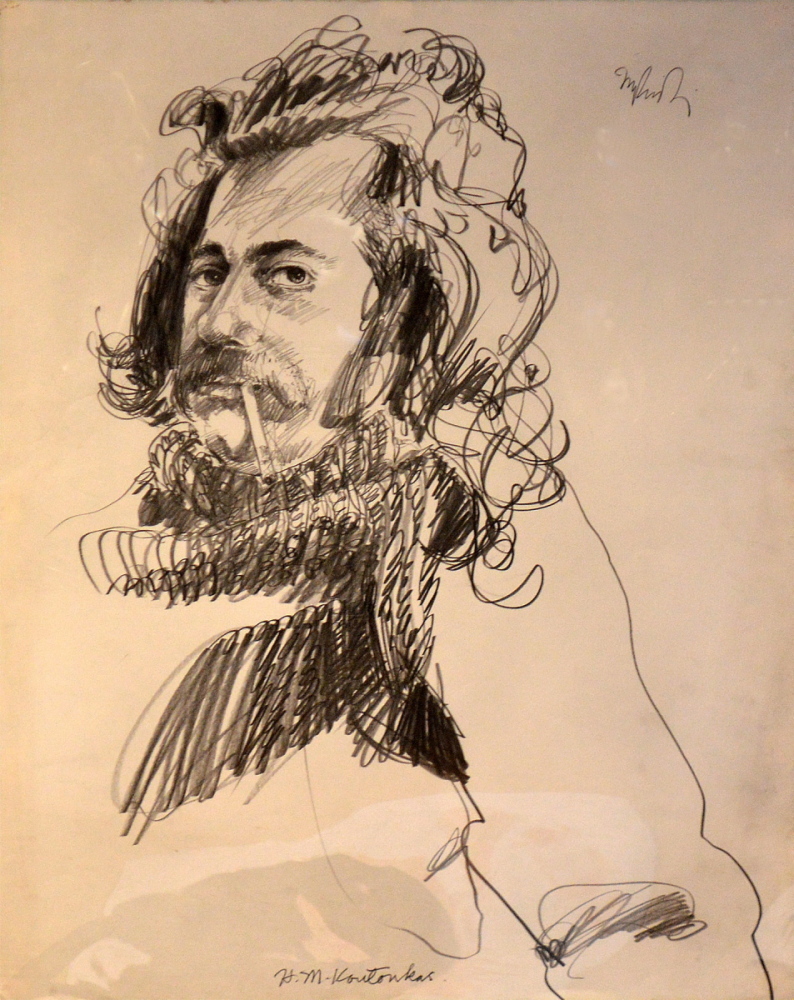

Walking into the gallery, you first see drawings by Mario Rivoli – a Denver artist whose beaded flowers have long been an ambient accessory in Portland’s most comfortable gallery. Rivoli’s show component comprises a suite of portrait drawings from around 1971 when he and Pollack were friends living in New York City. While your first impression might be that the works are dated, it only takes a moment to notice Rivoli’s extraordinary draftsmanship. His “H.M. Koutoukas,” for example, looks like Oz’s Cowardly Lion recast as a questionable detective in “Dirty Harry.” Rivoli’s pencil flies over his subject’s wild mane and flutters deftly amongst the folds of his then-chic turtleneck sweater. Koutoukas’s penetrating gaze is accessorized by a cigarette jutting out from under his fabulously manly moustache.

It’s an extraordinary drawing. Koutouskas clearly wanted to be a character and Rivoli was happy to indulge him. Yet, while the style and aesthetic of both the drawing and the model reach back to a very specific moment of American culture, Rivoli’s energized and masterful pencil work lift this drawing to something much more dynamically vital than an ephemeral snapshot. Pollack has made available paragraphs Rivoli wrote about each of his subjects, and the bit about Koutoukas resembling Rodin’s Balzac rings true: He is an essentially timeless type.

Bookending the show is Wyatt Barr’s set of six portraits recognizable as six homeless men from the streets of Portland. The images look like Chuck Close-style portraits created by clicking the “artistic/paint daubs” effect in Photoshop. However, a closer look reveals these are technically extraordinary ink-wash drawings. The constricted value of the images that dovetails with their flatly matte texture is the result of a rare (unique?) technique in which Barr lays down about 30 layers of liquid masque, each washed very thinly with sumi. The aggregate layers, he explains in a statement posted with the work, build up into “a thick coating of rubberized masque, which I peel off and discard in the trash bin like the molted skin of some alien creature.”

While I am no fan of work that requires content explanation, this transparency is welcome: This is a technique that we could not possibly fathom unless the artist explains it.

Barr’s work binds itself to Rivoli’s with unexpected force. Rivoli’s only color work is a portrait of “Danny Morales.” While his afro and sensuous lower lip could help him pass for some kind of star, Rivoli’s tender quip about him reveals Morales was just out of prison and “really interested in something to eat.”

While Rollin Leonard and Clint Fulkerson are more about numerical logic and steps in drawings, their work also ties in with unexpected elegance. Leonard is represented by three works. Two are digital drawings using dozens of images of a single model’s arm. The other is a video portrait in which a model’s head is divided into 17 bands rotating at various speeds and lining up every 36 seconds. It’s the math of musical harmonics or highly composite numbers, but it first reminded me of the solar system, with the top Mercury-quick and the bottom Pluto-slow.

While the “Lilia/360Ë” video is entrancing, its companion works are surprising subtle. One looks like an anemone or a ball of twine created out of several hundred different photographs of one person’s arms. It’s a work that gets more fascinating the longer you consider it: rather than a pastiche of different parts, it feels like a unified, single organism. On one hand, its repeated units align it directly with the traditional post-impressionist style of Barr’s drawings, but on the other hand, it reaches towards the fractal math of Fulkerson’s abstractions.

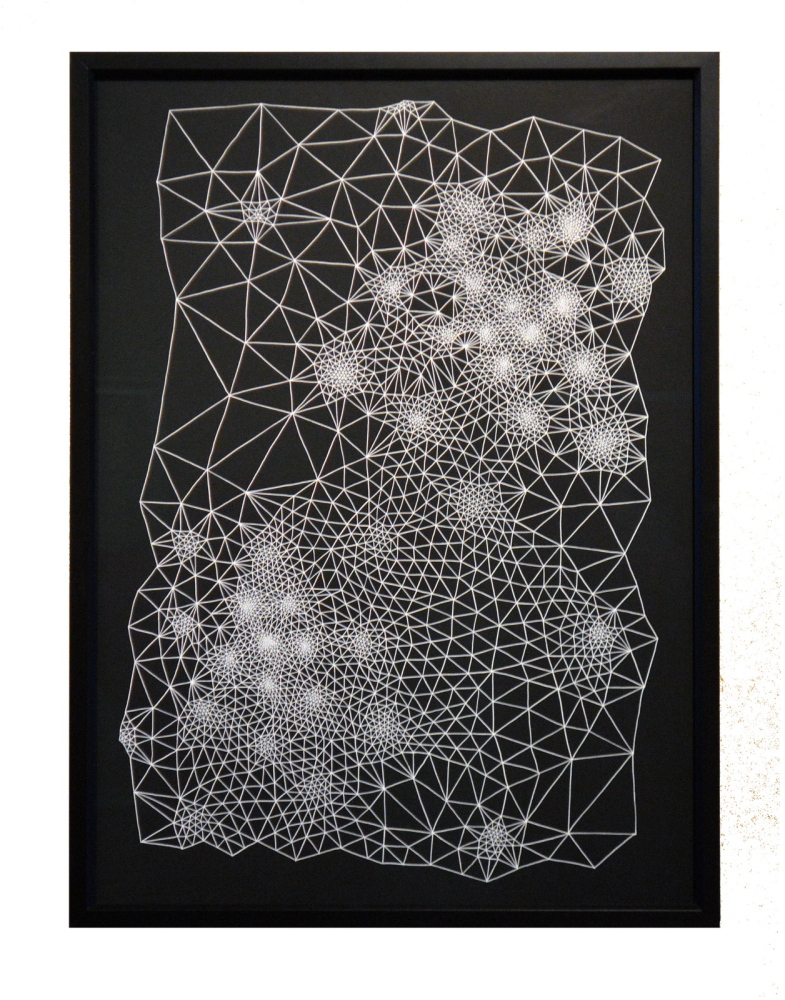

Fulkerson’s elegantly presented drawings are self-consciously geometrical, but they are made one line at a time (either black ink on white paper or white on black paper) and so develop with the natural/biological fractal logic underlying both modes of Leonard’s work.

Fulkerson is one of Maine’s most promising emerging contemporary artists; and seeing his work in this context-rich show is particularly revealing.

Fulkerson’s work also interacts with Kimberly Convery’s scribbly-wit drawings. While Fulkerson’s systems are geometrical and only seem to ironically gambol into art history jokes (Vasarely, Escher, etc.), Convery’s scenes have a New Yorker cartoon feel via their lighthandedness and diminutive scale. They appear to find sense and then fall apart. A few, however, seem to be straightforward landscapes, but even in this mode, Convery’s spatial quirks can’t help but wink and twinkle.

Pollack has curated a show in which the artists’ work all shines back on the others – bringing out the best in each. It’s one of Maine’s best drawing shows of 2013.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.