Masonic temples are designed for the decidedly private rituals of a generally male-only secret society. So to have a young woman as artist-in-residence may very well be unique.

Sarah Bouchard has persuaded the Portland Masons to allow her to use their Congress Street building as her canvas – and inspiration – for a large-scale installation. The dates for the Portland exhibition have not yet been set, but a strong selection of Bouchard’s process drawings, photographs and maquettes is now on display at the University of Maine at Farmington Art Gallery. While the Masonic Temple project offers the most interesting analysis of gender and society, the show comprises several chapters of Bouchard’s art that address subjects such as romantic relationships, organic regeneration and sign systems.

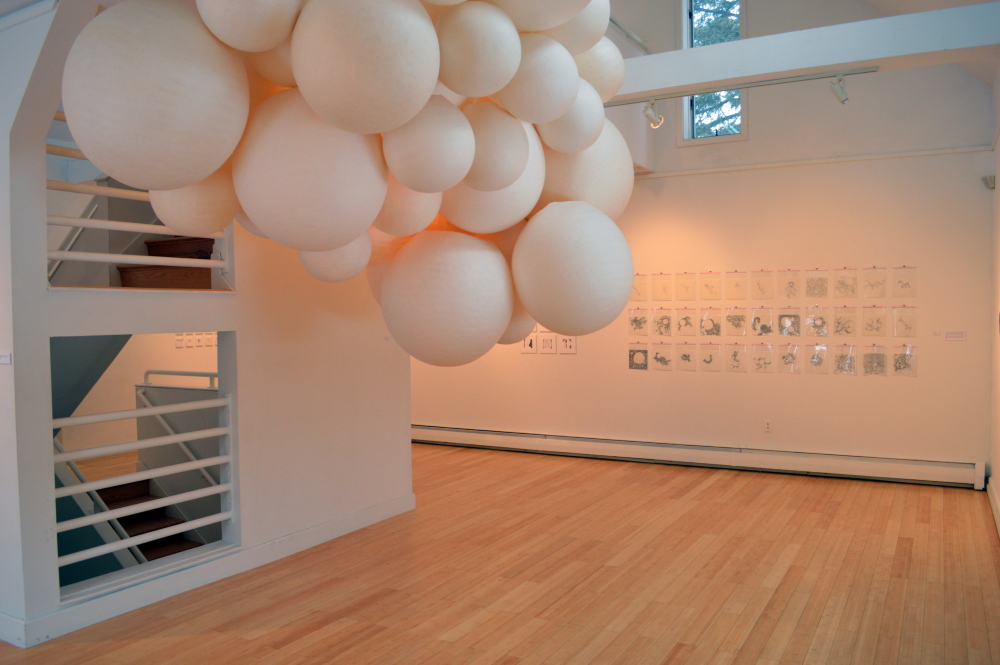

The portion of the exhibit designed for the temple is highlighted by “Orbs,” a very large and extremely beautiful hanging group of white handmade paper spheres up to 4 feet in diameter. Because it was necessarily installed in the UMF gallery’s lofting second-floor space, the show is essentially reversed, with the defining aspects of “process” coming in the second half of the show on the upper floor.

All around “Orbs” are study and process works that lay out Bouchard’s symbolic engagement with the extraordinary depth of the Masons’ iconography. She includes photographs of their space, ritual objects, Masonic symbols, a monument to George Washington and a range of drawings and collages that model the large-scale spherical installations she is planning, along with hints about the inspirations for the spherical forms.

Basically, Bouchard tasks herself with employing a female-oriented iconography that takes on the patriarchal Masonic symbols in a complementary, or dialectical, way rather than in terms of conflict or counterbalancing. For example, instead of creating a patriarch/matriarch structure, Bouchard sets the notion “patriarch” off from ideas like “maternal” or “female.” In fact, this very approach is the model for the philosophical distinction she sets out to convey.

Bouchard sets the notion of eternity via memorials for the dead – like Washington – against a fertility model of continuance: eggs, hives, birth, growth and so on. And while these are subtle distinctions, Bouchard makes them work.

Bouchard’s paper “Orbs” clearly relates to a beehive. This is explored in drawings and laid bare by an encyclopedic image of a bee making its paper nest. While this queen-led society might seem to diverge harshly from the Masons’ world, Bouchard comfortably connects them with images of the masons’ hive-like compartmentalized ritual hat boxes and her ever more insistent hints that the secret society is a centralized society with the temple as its hive. Instead of conflict, Bouchard again and again finds common ground.

Starting on the gallery’s first floor without the Masonic project for context is a furtive undertaking. An image of a fire behind a large farm’s planted field doesn’t necessarily bring to mind the Phoenix-like pairing of destruction and rebirth that becomes clearer after viewing the Masonic project.

Yet Bouchard displays conceptual depth with her insistent handling of grids and series. One generally difficult aspect for viewers of contemporary art, from Warhol on, is work that uses multiple images. But “process” includes many series of multiples that Bouchard elegantly handles with an impressive range: a witty grid of 33 plastic bags holding exquisitely complex sperm/egg circle drawings, a narrative-like line of 20 bittersweet images reminiscent of time-faded romance, a snappy systems set of 20 eight-color “8-bit” line drawings on panels, among others.

Instead of continuing with her modernist grids, Bouchard largely hangs the Masonic images “salon-style.” It’s a witty wink to the famously patriarchal French Academy’s annual exhibition – “The Salon” – that ruled European art through the 19th century. And it really works.

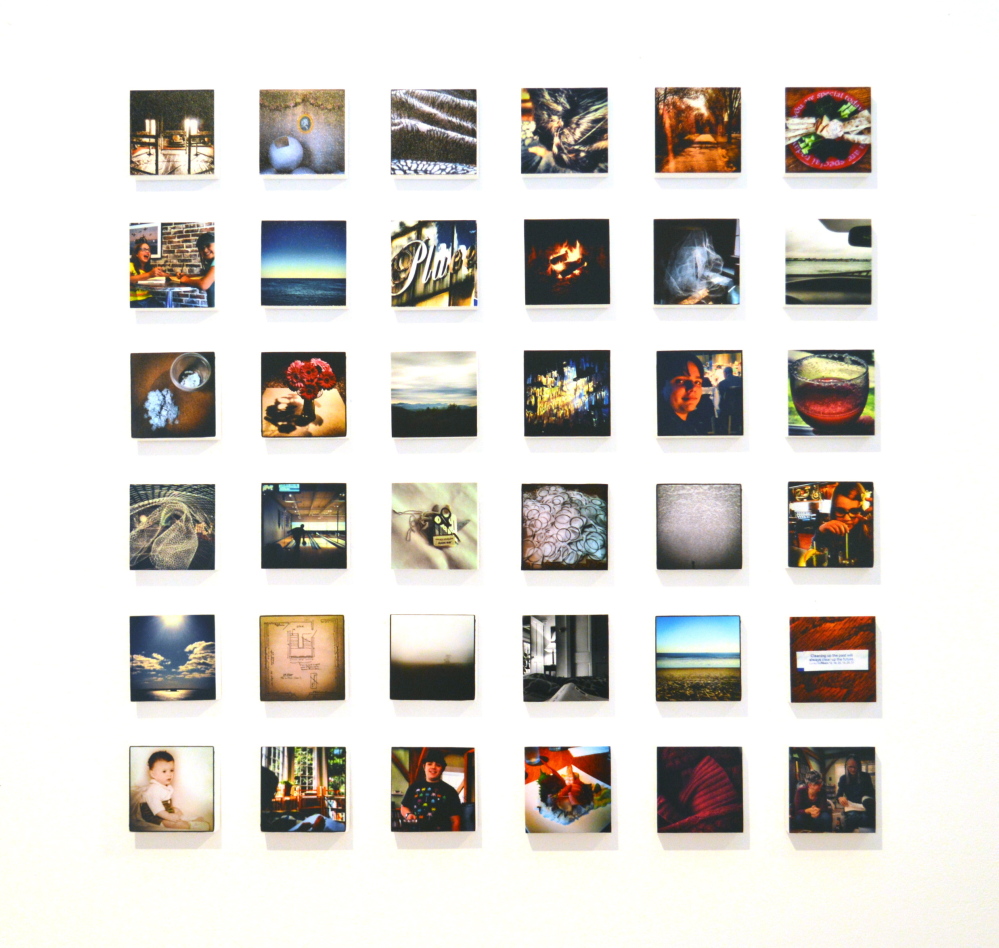

Bouchard’s most revealing and handsome grid is “Untitled,” a six-by-six set of 4-inch white panels on which she mounted a range of color photos that read like a friendly but impersonal tour of her personal life. What makes this piece so unusual is the ease with which it reveals its position that along with multiple images come multiple perspectives – a Romantic idea that runs directly counter to scientific repeatability.

While I am no fan of relying on label copy to understand work, Bouchard’s very well-written label texts admirably reinforce their content. Instead of explaining specifics of the personal photos, the label quotes Francisco Varela: “Reality is not a given: it is receiver-dependent.” In other words: The most important perspective is the one that you – the viewer – brings to encounter any work of art.

In fact, this arm of feminist thought dovetails perfectly with the self-determination of Enlightenment philosophies that drove people like George Washington to Freemasonry (notwithstanding the practical fact that secret societies offer convenient places to plot revolution).

In the end, Bouchard presents an extremely different world view from monuments to dead patriarchs or time-blurred ancient rituals conducted by exclusive groups. The surprise, however, is the warmth with which Bouchard and the Masons seem to regard each other (a photo of a ritual, for example, feels like it reveals their trust in her rather than any journalistic betrayal on her part). This nurturing warmth is a facet of feminism that is often intentionally overlooked – open-minded respect for others. However quiet, Bouchard is impressively clear: The final line of her title’s dictionary definitions of “process” reads: “3. To gain an understanding or acceptance of.”

“Process” may be challengingly subtle, but it is a deep, appealing and impressively successful exhibition.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.