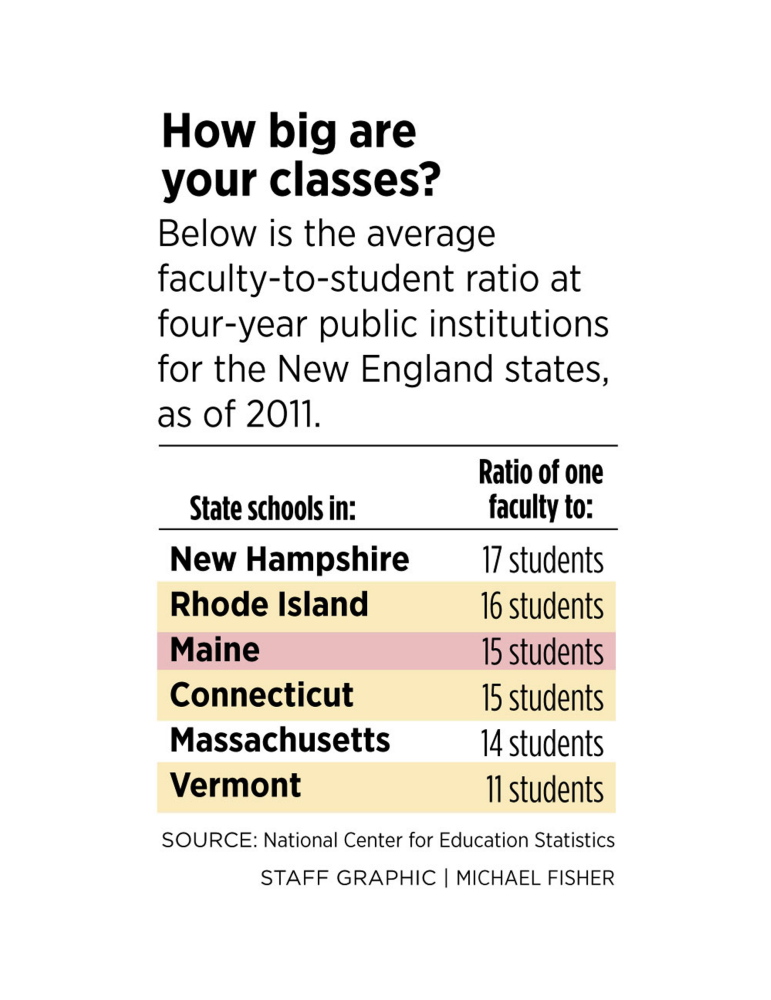

The national average faculty-to-student ratio for public four-year institutions of higher learning is 1-to-15. But planned budget cuts would raise that ratio at the University of Southern Maine to a level that outstrips the average for public universities in every state.

The budget cuts at USM call for raising the faculty-to-student ratio from its current 1-to-15 to 1-to-23. The average ratio for Maine’s public universities now is 1-to-15, according to 2011-12 data from the National Center for Education Statistics, which collects and analyzes data for the U.S. Department of Education. Florida’s four-year public institutions had the highest average faculty-to-student ratio of all states, at 1-to-22. The lowest were the District of Columbia, Wyoming and Colorado, which had averages of 1-to-10.

“I think it’s extremely shortsighted,” USM Faculty Senate Chairman Jerry LaSala said of the change. “It’s not good for the future of the university to set goals so unreasonable.”

As many as 30 faculty members would be laid off and four majors eliminated under the budget cuts laid out by USM President Theodora Kalikow.

The faculty-to-student ratio is an average across a school and may not reflect variations in certain programs, but it is a factor considered by prospective students to gauge campus culture and is tracked by annual “best of ” lists, including U.S. News and World Report’s well-known school rankings list. Many schools and programs tout a low faculty-to-student ratio on their websites and in marketing materials as one factor in offering students the best academic experience.

The USM faculty cuts are part of an effort to close a $14 million budget gap for the year that starts July 1. It is part of a larger $36 million funding gap in the University of Maine System caused by flat state funding, declining enrollment and tuition freezes.

On Wednesday, University of Maine at Augusta officials announced that they would cut 24 positions, end several degree programs and drop two sports teams. Officials at the flagship campus in Orono plan to announce this week how they would close a $12 million gap.

On March 14, Kalikow proposed cutting four academic programs and as many as 50 faculty and staff positions. Layoff notices announced Friday brought protests from students and faculty, with students protesting outside the provost’s office as faculty members to be laid off arrived for meetings with the provost.

Objections to the proposals reveal a deep divide between those who question the need for such deep cuts and defend an academic tradition of research even in fields with low enrollment, and those who say universities should be run like a business, with graduating students the marketable product.

Some students and faculty members worry the college experience will suffer with such a tight focus on financial efficiency, particularly plans to make classes bigger, end underenrolled programs and maximize teaching time for faculty.

“What you’re describing is a diploma mill. This is not about creating a vibrant academic community,” recent USM English graduate Phillip Shelley told Kalikow at a campuswide meeting last week. “Education is not content, it’s not something that is delivered. It is not a product. It is not a service. It is a public good. It’s the way a civilized culture reflects on itself and evolves.”

‘A REASONABLE RESPONSE’

USM Provost Michael Stevenson said Thursday that the 1-to-23 ratio is “an estimated target, not a firm goal” and could be achieved without sacrificing quality.

Stevenson said undergraduate classes should have 30 students, and graduate courses between 15 and 18 students. Tenured faculty should teach three courses a semester – something most already do – and the school should offer yearlong course schedules, covering both semesters, instead of announcing course offerings only for the upcoming semester.

Those changes are projected to shave $2 million off the current $4 million a year spent on part-time and “overload” instructional costs – in which faculty are paid extra to teach more than their usual three courses a semester.

“These types of cost-saving strategies will, over time, minimize the needs for such drastic actions as position eliminations,” Stevenson said. “I think it is a reasonable response to our fiscal pressures and the realities of our enrollment situation.”

Between 2008 and 2012, enrollment dropped 6 percent at USM. It had 8,923 students enrolled at the start of the current academic year.

Class size isn’t a fixed number, and represents an average across hundreds of classes, Stevenson said. Some introductory courses are regularly taught to hundreds of students at a time, while higher-level courses, or certain disciplines such as music or art, regularly have classes with just a handful of students.

But several speakers at last week’s campus meeting with Kalikow questioned how USM would be better serving the students – something Kalikow says is the foremost mission of the university – if it was adopting a policy of bigger classes.

“No student was ever served by decreasing her access to faculty,” classics professor Jeannine Uzzi said. “This is not what the economic engine of the state needs: fewer faculty.”

HIGHEST RATIO AMONG PEERS

Kalikow said many of the changes being proposed are “guided” by the idea of a higher faculty-student ratio.

“We’ll continue to decrease our reliance on part-time faculty, make strategic use of full-time, non-tenure track faculty where it makes academic sense, and hold to the principle that tenured faculty members are at the heart of any high-quality program and provide essential continuity for long-term success,” Kalikow told the Faculty Senate on March 14. “These decisions will be guided by peer-derived benchmarks, especially the faculty-to-student ratio of 1-to-23 at peer and aspirational peer institutions.”

However, the 1-to-23 ratio is still higher than at any of USM’s peer institutions, which have been used for years by the university as the official “comparable” institutions and are listed on the campus website.

Of the eight universities USM cites as peers, Kennesaw State University in Georgia has the highest ratio at 1-to-22. The lowest is North Carolina Central University, at 1-to-15.

LaSala described the proposed 1-to-23 ratio as “an extreme outlier.”

The University of Maine in Orono has a faculty-to-student ratio of 1-to-16, according to spokeswoman Margaret Nagle. She said the school does not keep data on the number of courses faculty members teach in a semester.

Stevenson said cutting costs this way doesn’t mean sacrificing quality.

“We are trying our best to move in the direction of providing that high-quality experience in a fiscally sustainable way,” he said.

However, some faculty members have pushed back on the idea that cutting funds would have no effect on teaching quality.

“I’m concerned that the perspective is one of bean counting alone, and not a concern of quality,” said Mark Lapping, a professor at the Muskie School of Public Policy and a former USM provost, at the meeting where Kalikow announced the cuts. “At the end of the day it’s about academics. If it isn’t about quality, if it isn’t about service, screw it.”

COMPARATIVELY UNSCATHED

Maine’s public institutions of higher learning have fared better than many public institutions in other states, in part because the University of Maine System froze tuition in exchange for flat state funding. Many other state universities have made deep cuts, mostly because of the recession and strapped state governments that cut funding, according to a 2013 report from the Washington, D.C.-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Among the cuts cited in that report: The University of New Hampshire has eliminated nearly 200 staff positions, implemented a hiring freeze, and froze staff salaries; the University of California system consolidated or eliminated more than 180 programs; Arizona cut 2,100 positions and consolidated or eliminated 182 colleges, schools, programs and departments; and the University System of Louisiana has cut 217 academic programs.

Those cuts have likely raised the faculty-to-student ratio at many colleges in the last year, but are not yet reflected in annual federal education statistics. Just the week before last, when USM announced its cuts, officials at Southern Oregon University announced a similar scenario: That school is cutting 25 faculty positions, phasing out seven majors and three co-majors, 11 minors, two certificates, and eight major concentrations, boosting its ratio from 1-to-17 to 1-to-21.

USM associate professor Matthew Killmeier said there has already been a slow increase in class size in his department, Communication and Media Studies. When he started in 2002, introductory classes were capped at 30 students, and now they are capped at 40.

“We’ll probably go higher than that now,” he said. “The big impact is that with extra students, there are certain things you can’t do.”

For example, he said, he can’t assign many short papers because students couldn’t get them back in a reasonable amount of time.

Early online-only courses, he said, were capped at 18 to 20 students, and now many are at 25 or 30 students.

“It makes economic sense that you would want to educate more students, and some faculty would argue you can do this” without sacrificing any quality, he said. “There are differences of opinion and it varies by discipline.”

But in general, “nobody brags about a higher number,” Killmeier said. “That’s one of the metrics people look at. You’re going to get a more individualized experience in a smaller class.”

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 7:05 p.m. on Monday, March 24, 2013 to correct University of Southern Maine enrollment information. USM had a Fall 2013 enrollment of 8,923 students.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.