As Woody Allen once said, 80 percent of success is just showing up.

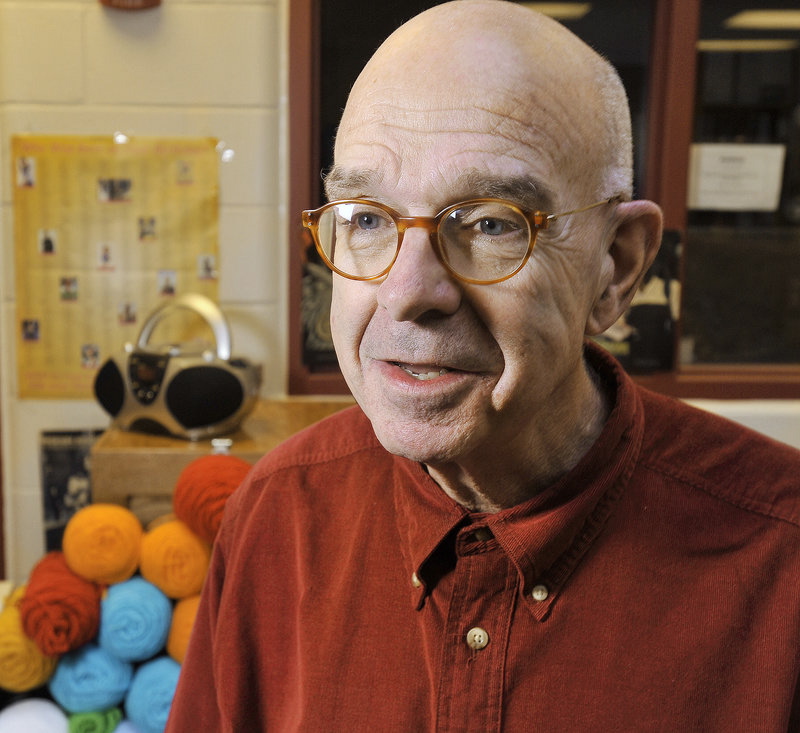

The quote popped into Dan Reardon’s head one day a few years ago at the Long Creek Youth Development Center in South Portland, where he was being honored for his years as a volunteer.

“One kid stood up and, stuttering and stammering, he said, ‘You know, if Dan tells you he’s going to be here, he’s here. If you plan on doing something on a certain day and it’s a day when Dan comes in, he’s always here,’ ” recalled Reardon in an interview on Tuesday. “It made me think that, really, what I’ve done is show up.”

His wistful tone spoke volumes. Much as he’d still like to spend 15 to 20 hours of his valuable time each week with those kids many people prefer to ignore, Reardon is persona non grata at Long Creek until further notice. Maybe forever, for all he knows.

Make no mistake about it – Reardon messed up.

Last month, well aware that as a volunteer he has to abide by the detention center’s rules like everyone else, he violated one: A boy resident asked Reardon to deliver a note to a girl resident and, rather than refuse because note passing is verboten, Reardon did as the kid asked.

That was on a Friday. By that Sunday, Reardon was on the phone confessing his transgression to Long Creek Superintendent Jeff Merrill II, who already knew about it.

The next day, upon meeting briefly with Merrill, Reardon was prohibited from setting foot on the premises.

What’s wrong with this picture? Two things.

The first is obvious: Having spent the last quarter-century donating countless hours and resources to kids who aren’t used to getting much from anybody, Reardon of all people should have known that the rules – even against something so benign as passing a note – are the rules.

“I broke a rule,” said Reardon. “And then I said, ‘What’s the best thing to do? The best thing to do is just admit it, get it over with.’ ”

Still, beyond Reardon’s reflexive mea culpa, another question lingers: Does the punishment – indefinite suspension – fit the crime? Why not, say, a month off followed by a refresher course on volunteer-resident boundaries?

To put it more bluntly, is this an inevitable consequence of wrongful conduct? Or is it an excuse to get rid of an irksome outsider whose sensitive nature connects with the kids while rubbing some paid staffers the wrong way?

Conflicting philosophical currents have long flowed through what began in the 19th century as a farm where Maine’s most recalcitrant youths might learn the value of hard work and, in the process, straighten out their lives.

One side sees Long Creek as all about rehabilitation, providing kids a second (and, if necessary, a third and fourth and fifth) chance to save themselves, while there’s still time, from the endless cycle of crime and punishment, crime and punishment …

The other side casts the kids, admittedly Maine’s most troublesome, as hellions in training, all-but-lost causes who need to be contained and controlled, not comforted or coddled.

From the day he first walked into what was then the Maine Youth Center, Reardon has put himself squarely in the rehabilitation camp.

It was the late 1980s and, as president of Maine-based G.H. Bass & Co., Reardon was looking to give away a load of surplus shoes and clothing. A friend suggested the youth center and, said Reardon, “I saw what was going on and I never stopped going back. I tend to believe it was God’s hand in my life.”

Soon, he was stopping by Cottage 3 (one of six at the time) each Sunday, arms brimming with food he’d purchased from his own wallet. An avid cook, he and the cottage residents would prepare a Sunday dinner, along with a much bigger batch of dessert to be shared with every kid in the joint.

“It wasn’t just feeding the kids,” said Reardon. “It was a way to talk, to develop relationships.”

Along with the center’s chaplain, Reardon also started a support group for any kids who wanted to attend. It continued right up until last month.

“We just talk about what’s on their minds, what’s bothering them, what they’re happy about – things of that nature,” he said.

The Sunday dinner ended a decade ago with the opening of the Long Creek Youth Development Center and its centralized food service.

But by then, Reardon had founded The Blanket Project, a weekly crocheting session through which male residents have turned out thousands of blankets, hats and other items for their loved ones and the community at large.

I visited the project just over two years ago. Like others who have witnessed it, I was dumbstruck at the sight of two dozen young men, as rough as they come, diligently teaching one another this or that stitch. One, a 19-year-old named Shane, was working on a reggae-style blanket for his 2-year-old son.

Little wonder that when Long Creek residents fill out an exit questionnaire as they leave the center, they almost always cite Reardon as the person who had the most influence on them during their stay.

Or that several former residents, upon reading fellow volunteer Bill Linnell’s Facebook tribute to Reardon this week, took to their keyboards to sing his praises.

“He always knows what to say, he’s always there for you which not many of us kids had that growing up,” wrote Thomas Travis of Sanford. “And if he wasn’t sure what to say or do (which is almost never) he was still there to listen. Which was more than enough for me. Dan is the nicest man I have had the privilege of knowing.”

Zebulon Olson was once a resident at Long Creek and is now pursuing a degree in architectural engineering – thanks in no small part to Reardon, he said in an email late Tuesday.

“Too many people, in my mind, deem people saints,” Olson wrote. “But truly, and I’m not a religious man, I would have to say Dan is as close as they come. Taking Dan away would be a crime itself.”

Tuesday was Volunteer Appreciation Day at Long Creek, a chance for the staff and residents to thank the 275 good souls who give their time and talent to a population that is accustomed to receiving neither.

Reardon, who has faithfully “shown up” at Long Creek every Monday, Wednesday and Friday evening and all day Sunday, was not there to get his annual pat on the back. The Blanket Project, according to Department of Corrections spokesman Scott Fisk, “is on hold for now … If (Long Creek) had someone who could have kept it going, they would have.”

Back before he left G.H. Bass in 1998, Reardon was asked by an employee why he (and his company) fixated so constantly on those kids atop the hill in South Portland.

Replied Reardon, “When I die, I don’t want them to write on my tombstone, ‘He sold more shoes than anyone else in the world.’ I want them to say, ‘He did this kind of work.’ Because that’s what counts.”

It still should.

Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at:

bnemitz@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.