Early in his absorbing new memoir, acclaimed author and poet Richard Hoffman describes a childhood routine that suddenly changed.

The 6-year-old Hoffman and his little brother would brush their teeth at bedtime, then run to kiss their father goodnight. But one night, their dad inexplicably countered with a handshake instead.

More than half a century later, that halting gesture remains part of the puzzle of Hoffman’s father, a central figure in this epic family tale.

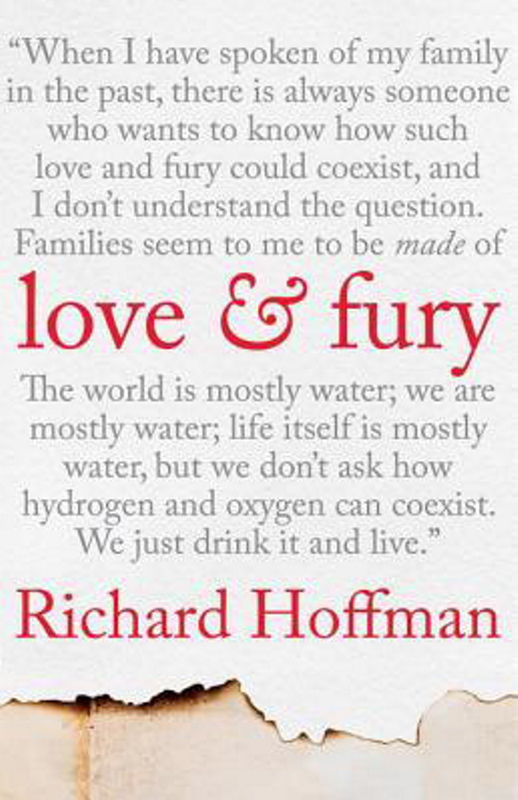

“Love and Fury” is Hoffman’s wide-angle appraisal of his father and the masculine culture of his times. Part memoir and part polemic, the book serves as a meditation on class and race by the first member of his family to attend college, a striver who aspired to middle-class respectability. Now 65, Hoffman is writer-in-residence at Emerson College and a former faculty member at the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast MFA program.

Hoffman’s story begins around the proverbial kitchen table, with two middle-aged sons being summoned by their ailing dad for the conversation that every family dreads. A steel box and assorted final documents sit between the two generations. By book’s end, we attend the father’s funeral, having witnessed the love and fury of the book’s title and the sweeping inquiry that is the book’s mission. Who was Richard Hoffman Sr., and what does it mean to be a good man in today’s world?

In his search for answers, Hoffman considers five generations of men in his family – from his grandfather, who worked in Pennsylvania’s coal mines from the age of 10, to his young grandson who faces a different set of hardships. Yet throughout, he trains his eye on his dad, who remains an inscrutable mass of contradictions. He could be violent and brusque, a racist and reductionist, who was also determinedly decent.

By viewing his father in the context of his place and times – as a working-class Catholic, World War II paratrooper, Boy’s Club coach and smoke ring virtuoso – Hoffman tries to make sense of the man. He leads us on a cultural odyssey that highlights images of war and misogyny, ranging from the 1950’s film “Attack,” starring Jack Palance, to Playboy magazine.

While Hoffman’s cultural critique is engaging, the book is best when it highlights stories from family life. When Hoffman’s 18-year-old daughter, then a college junior, announces that she’s pregnant, the result of a one-night stand, and debates whether to have an abortion, Hoffman counsels that it’s her decision. As he well knows, the circumstances are less than optimal.

“But what I felt, and what seemed to easily overwhelm my thinking was something else entirely,” he says. “I felt a hot splash of joy right in the center of my chest.”

Similarly, when the baby is born, his very existence challenges every bias that Hoffman’s father possesses. Indeed, this is a potential trifecta of bigotry – a baby of mixed race, born out of wedlock, whose father is a convicted felon of African American descent. And yet, when Hoffman’s dad meets his great-grandson for the first time, it’s an occasion of unabashed playfulness and pride, proof of the book’s repeated claim, “babies bring their own joy.”

If this were a work of fiction, readers might reasonably say that the author had overreached or piled on. The surfeit of real-life misfortune that has, in ways, defined Hoffman’s family is a virtual litany of our culture’s hot-button issues: Guns, drugs and childhood rape; addiction, abuse and rehab; bigotry, racism and inequality. Add to these the core sadness of Hoffman’s early years, when two of his younger brothers suffered and died from muscular dystrophy.

The author has shaped this difficult material into an astute, thought-provoking and lyrical narrative. That readers will be mulling issues of race and class long after finishing the book attests to Hoffman’s achievement.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.