Despite distractions, financial uncertainty and official harassment, Don Gellers was building a compelling land claims case for his Passamaquoddy clients.

In their first meeting in the spring of 1964, Pleasant Point tribal Gov. George Francis had told him that everyone knew about the tribe’s rights under a critical 1794 treaty, including ownership of a trust fund and vast tracts of subsequently stolen land. In fact, outside of the tribe, these had been entirely forgotten.

The Indians themselves had discovered the treaty just five years earlier in the possession of Louise Sockabasin, great-aunt to Indian Township Gov. John Stevens’ wife, lovingly wrapped in a centuries-old envelope woven from sweetgrass and tucked unceremoniously into a trunk. When Stevens first opened and read it, he says he screamed with surprise.

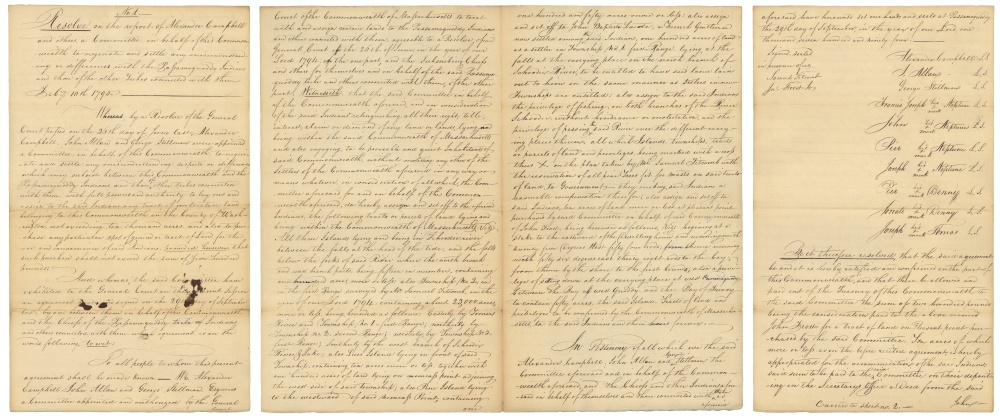

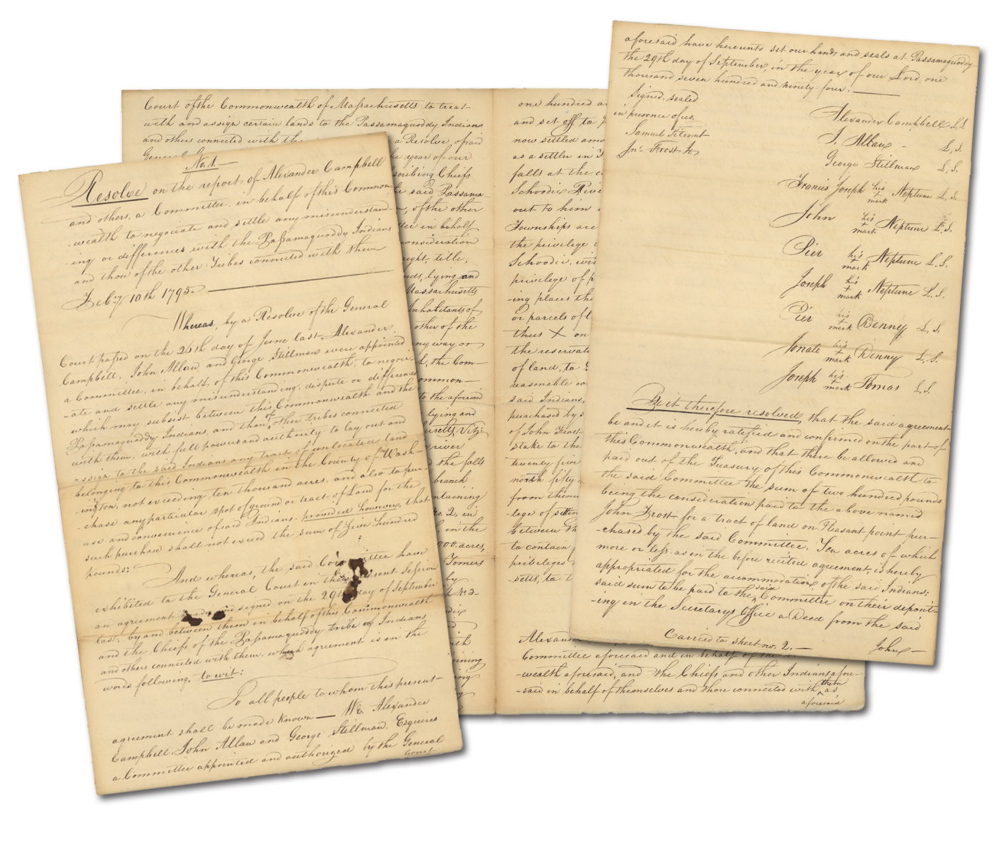

The treaty had been negotiated in 1794 with Massachusetts, which controlled Maine at the time, and under it the Passamaquoddy had surrendered their ancestral lands in exchange for perpetual ownership of 15 islands in the St. Croix River, two in Big Lake, 10 acres at Pleasant Point, and the entirety of what came to be called Indian Township, 23,000 acres of forest, streams and lakes in what would later be eastern Washington County that the tribe had used as winter hunting grounds since time immemorial.

Recognizing the Indians would not be able to sustain themselves entirely on this reduced land base, they were also given a trust fund – $37,471 in 1822, or $147 million if it had just been left to compound interest through 1964.

Gellers discovered that when Maine became a state in 1820, it received this trust fund and 395,000 acres of deeded land meant to provide for the Indians.

Under the separation agreement with Massachusetts, not only was Maine required to uphold the 1794 treaty obligations, but they were written into the new state’s constitution. They were found within Article X, Section 5, and remained in force.

However, learning what those obligations were wasn’t easy.

That’s because in 1875 the people of Maine ratified a constitutional amendment forbidding this article to ever be published. That amendment is still in effect: Open any copy of the Maine Constitution to Article X, Section 7, which proclaims Section 5 will “remain in force” but “shall hereafter be omitted in any printed copies.” Exactly why this was done remains unclear.

If the constitutional commissioners who proposed the change intended to ensure the state’s obligations were forgotten, it was effective. Rather than protecting the Indians’ trust lands, the state authorized some tracts to be flooded by dams, others to be annexed for the laying out of Route 1 in Indian Township and Route 190 at Pleasant Point, and thousands more acres transferred to white owners. In no case was compensation given to the Indians. In all, at least 10,000 acres had been stolen, among them the small plot where the gravel pile protest had taken place in 1964.

Maine courts had ignored the tribe’s treaty rights, rubber-stamping the annexation of their lands by powerful landowners such as William Bingham (for whom the mountain is named) and, in the infamous 1892 case of State vs. Newell, ruling the tribe no longer existed.

“Though these Indians are still spoken of as the ‘Passamaquoddy Tribe’ and perhaps consider themselves a tribe, they have for many years been without a tribal organization in any political sense,” the court ruled. “They cannot make war or peace, cannot make treaties, cannot make laws, cannot punish crime (or) administer civil justice among themselves.”

In other words, having denied the tribe these sovereign powers, the state was now using the absence of these powers as grounds to deny them not only their treaty rights but the rights other tribes were by then enjoying under federal law.

Gellers also discovered that nobody was able to provide an accounting of just what had happened to the trust fund accounts or to the millions in state-organized timber sales that should have been held on behalf of the Passamaquoddy who, after all, owned the trees. Much of this revenue – which belonged to the Passamaquoddy and no one else – had apparently been diverted into the state’s General Fund. In other words, the state had simply taken it.

As for the 1794 treaty, it had indeed been forgotten, and state officials were publicly dismissing its validity. Privately, however, Gov. John Reed’s administration was nervous.

After the Indians had visited Reed, apprising him of the 1794 treaty, state officials quietly wrote their counterparts in Massachusetts and Washington, D.C., asking whether they knew anything about it. Nobody did.

Just days after Gellers started representing the tribe, state officials became fearful he might try to secure federal recognition for the tribe. The commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs reassured them that “our research has revealed nothing to substantiate a belief that any federal control over or financial responsibility for the Passamaquoddy Indians has ever existed.”

Unable to carry the expense of the case himself, Gellers had turned to the Indian Rights Association, a Philadelphia-based social activist group dedicated to helping tribal people. After reviewing his early research findings, the group agreed to finance part of his expenses, although Gellers received no fees to support himself.

Around this time, Joseph Nicholas publicly accused Gellers of “exploiting the Indians for personal gain.” Gellers responded: “If I experience a great deal more personal gain of this sort, I just may starve.”

By the late winter of 1967, Gellers’ marriage had collapsed, just as his land case was coming together. He touted the latter to reporters as an effort to “redress 146 years of fiscal misdealings” by Maine.

Short-staffed, he asked the Law Students Civil Rights Research Council for a summer intern. A few months later, a young law student and his girlfriend pulled into the driveway in front of Gellers’ rambling Eastport home.

The intern got out of the car and knocked on the door. His name was Tom Tureen.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Coming tomorrow:

Fighting the police

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story