At its core, art in our culture is a transformative phenomenon. An artist takes mundane materials like a brush, paint and a canvas and transforms them – almost alchemically – into something with a powerful presence. Art can be critical or confrontational. Or it can whimsically re-imagine its subjects and let us in on fantasies, dreams and utopias. Just to imagine something, after all, is to transform it.

The culture of art struggles with this power – and often lashes back with realism or literalism. On one hand, we want artistic culture to be powerful enough to transform society, but we also hanker for the foothold of recognition.

Many of the most interesting shows on view around Maine this summer – from Estes at the Portland Museum of Art to the Shakers at the Farnsworth – rely on an ironic twist of initial recognition: We think we understand what’s going on at first glance, but the open door takes us somewhere else.

Aucocisco Galleries will be closing its doors forever on Sept. 12. It will leave a hole in the Portland art scene for many reasons, but one of the most notable relates directly to its current (and final) show – an exhibition of paintings by Bernard Langlais.

Langlais is the subject of a great retrospective currently on view at Colby College. And the most common response to the Colby show has been surprise about the extent to which Langlais was a compelling painter. But anyone who has regularly visited Aucocisco is quite familiar with this side of Maine’s most sophisticated historical primitivist.

Langlais is best known for his carved wooden sculptures of animals but his artistic fire was fed by his sophistication as a painter. And this is now on display at Aucocisco: Below the surface, Langlais was always a painter.

At SPACE Gallery, Adam Manley challenges our perspective in a different way. His “Staying Put” raises philosophical concerns about how art exhibitions are not necessarily what they first seem to be. Manley’s show features about 20 large photographs presented like paintings. They are joined in the gallery by a video projection and a large float on which is attached an oak dining table and four chairs.

If you head into the show expecting a photography exhibition, you will likely see a photography exhibition. After all, photographers often create sets, objects and costumes for their projects.

The exhibition presents the work as part “object” and part “installation,” but this too is misleading (in a well-orchestrated way) since it is clearly presented as an exhibition of pictures. The informative wall copy tells us about Manley’s goals: It says the work is “completed when it has lived, for a short time, in the waters of Maine.”

Some viewers may see sculpture. Some may see a meditation on the relationship between furniture-making and boat-building. Others may see conceptualism, installation or environmental art. But to me, this is theater. And while I generally dislike theater, I am a huge fan of the Theater of the Absurd and Eugène Ionesco in particular. And “Staying Put” feels like an epilogue to Ionesco’s “The Chairs” updated for a social media savvy audience.

Whatever Manley’s intentions were, his relying on a performance in which an empty stage is the main character makes this a powerful bit of brilliantly presented theater.

This brings us to the social media event of the summer, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which involves filming yourself having a bucket of ice water dumped on your head to promote awareness of the disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) when challenged by your “friends.” The creative and technologically edgy – and unabashedly absurdist – theatricality of this phenomenon combined with its cultural goal of awareness and advocacy qualifies it in my book as one of the largest American art projects ever.

Don’t agree? Then head over to Greenhut Galleries to see Jon Imber’s luscious, rich and vigorous pastels. (The exhibition closed Aug. 30 but works are still on view.) The long-time Harvard professor and leading figure of the Down East art world died this year of ALS and the film “Jon Imber’s Left Hand,” which documented his illness and its effects on his body, his art and his family, will very likely be long considered a masterpiece of understanding the tragedy of ALS.

Imber’s works were always powerful, but now they have to be seen as heroic.

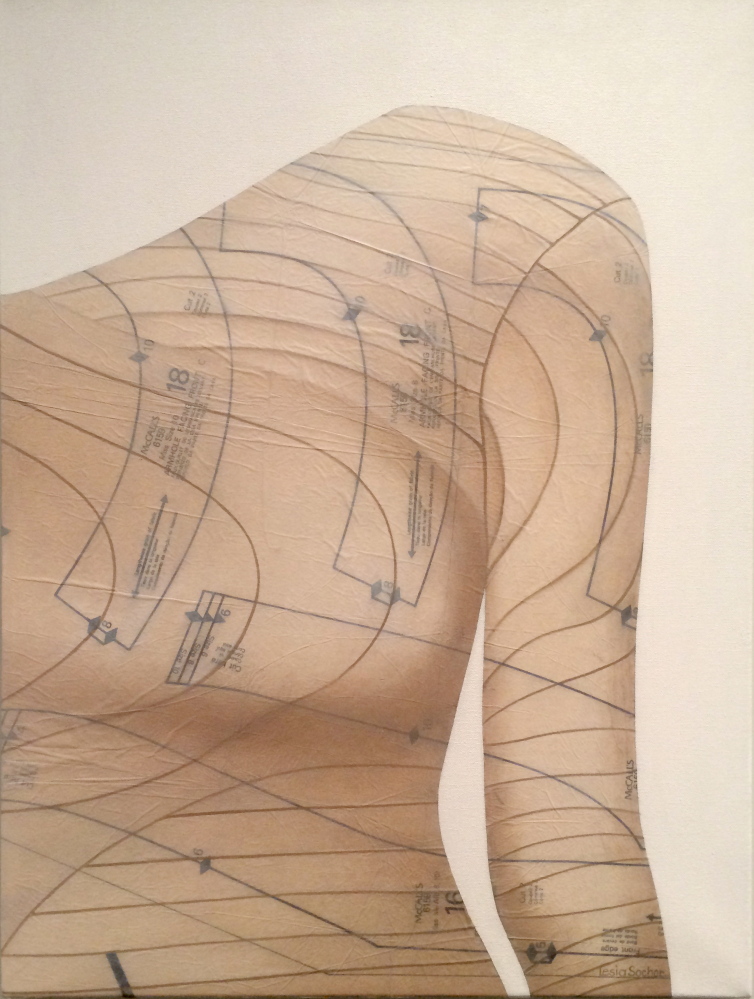

A particularly interesting this-is-not-what-it-seems show is “Of Women by Women” featuring the work of Veronica Cross and Lesia Sochor. It features several “unseen” themes including female sexuality, the relation of range and repetition in garment sizes and, most subtly, collage.

Cross’s exciting and brazenly sexual work comes as a quiet assault on painting. Her cut-outs’ focus on contour ties them to drawing and the braininess that implies, but her content is concerned with the unseen. A nymph, for example, is a silhouetted shape (an absence? a trope?) but the complementary satyr is merely implied by shadows that might be just a tree. It is an image of fantasy as the source of both possibility and doubt.

Sochor’s images take on sewing patterns in a sharply smart meditation on individuality and repeatability in fashion. (She focuses on the grading of patterns – the marks to adjust for different sizes.) Two blouses, for example, appear almost indistinguishable but are labeled “Mother” and “Daughter.”

Cross’s and Sochor’s powerful pairing moves together from something as simple as sewing to realms that explore the philosophical sovereignty of the body.

The most exciting work in this theme, however, is now on view at ICA. “Fair Use,” part of the “Project_” installation, looks like a thoughtful survey of commonly seen architectural archetypes (archetecture?), but is then revealed to be a controversial investigation into copyright. Also at the ICA is an exhibition of paintings by Maine State Prison lifers that raises all kinds of questions about freedom, freedom of expression and cultural conventions. We’ll have to revisit these shows in a future column. They demand a much closer look.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. Contact him at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.