They have clicked links in bogus phishing emails, opened malware-laden websites and been tricked by scammers into sharing information.

Federal employees and contractors scattered across more than a dozen agencies, from the Defense and Education departments to the National Weather Service, are responsible for at least half of federal cyberincidents each year since 2010, according to an Associated Press analysis of records.

One was redirected to a hostile site after connecting to a video of tennis star Serena Williams. A few act intentionally, most famously former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden, who downloaded and leaked documents revealing the government’s collection of phone and email records.

Then there was the contract worker who lost equipment containing the confidential information of millions of Americans, including Robert Curtis, of Monument, Colorado.

“I was angry, because we as citizens trust the government to act on our behalf,” he said. Curtis, according to court records, was besieged by identity thieves after someone stole data tapes that the contractor left in a car, exposing the health records of about 5 million current and former Pentagon employees and their families.

At a time when intelligence officials say cybersecurity now trumps terrorism as the No. 1 threat to the U.S., an AP review of the $10 billion-a-year federal effort to protect sensitive data shows that the government struggles to close holes without the knowledge, staff or systems to keep pace with increasing attacks by an ever-evolving and determined foe.

While breaches at businesses such as Home Depot and Target focus attention on data security, the federal government isn’t required to publicize its own data losses, with news of breaches emerging sporadically.

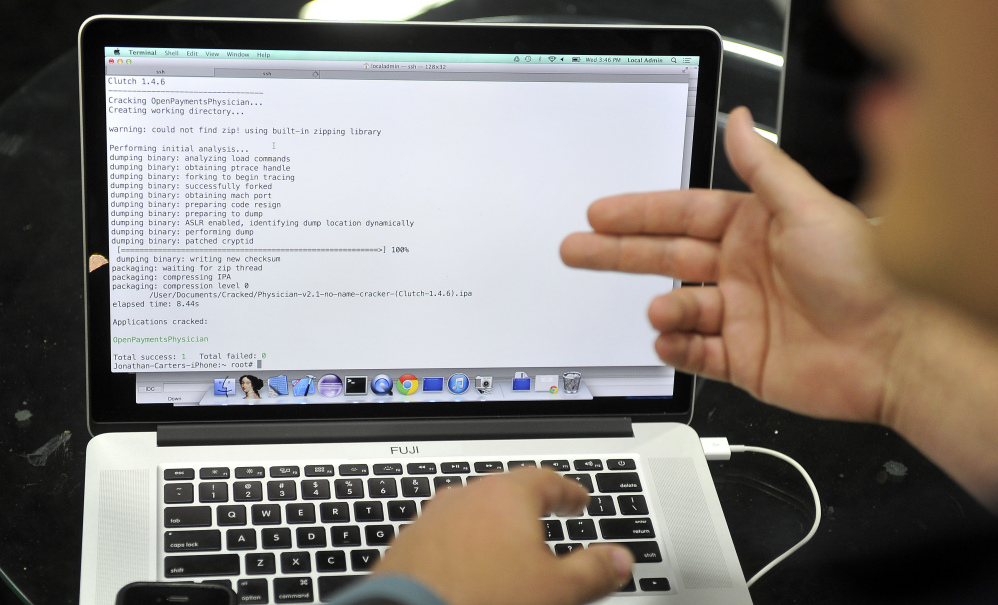

HACKERS FIND A WAY

On Monday, the U.S. Postal Service said it was the victim of a cyberattack and that information about its employees, including Social Security numbers, may have been compromised. And last month, a breach of unclassified White House computers by hackers thought to be working for Russia was reported not by officials but The Washington Post. Congressional Republicans complained even they weren’t alerted to the hack.

“It would be unwise, I think for rather obvious reasons, for me to discuss from here what we have learned so far,” White House press secretary Josh Earnest later said about the report.

To determine the extent of federal cyberincidents, which include probing into network weak spots, stealing data and defacing websites, the AP filed dozens of Freedom of Information Act requests, interviewed hackers, cybersecurity experts and government officials, and obtained documents describing digital cracks in the system.

“It’s a much bigger challenge than anyone could have imagined 20 years ago,” said Phyllis Schneck, deputy undersecretary for cybersecurity at the Department of Homeland Security, which runs a 24/7 incident-response center responding to threats.

Fears about breaches have been around since the late 1960s, when the federal government began shifting its operations onto computers. Officials responded with software designed to sniff out malicious programs and raise alarms about intruders.

And yet, attackers have always found a way in. Since 2006, there have been more than 87 million sensitive or private records exposed by breaches of federal networks, according to the nonprofit Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, which tracks cyberincidents at all levels of government through news, private sector and government reports.

By comparison, retail businesses lost 255 million records during that time, financial and insurance services lost 212 million and educational institutions lost 13 million. The federal records breached included employee usernames and passwords, veterans’ medical records and a database detailing structural weaknesses in dams.

SCARIER BY THE YEAR

Marc Maiffret, a hacker turned cybersecurity expert, said “today’s a little scarier” than when he was breaking into systems in the ’90s. Malware and viruses can be purchased or rented, so advanced coding skills aren’t required. And there’s more mischief to be made, because the government depends on technology for everything from missile targeting to student loan processing.

“There’s also a much bigger allure to use these skills to make money, in a criminal sense,” said Maiffret, co-founder of the cybersecurity firm Beyond Trust, whose customers include the military.

From 2009, when the government began breaking out different types of incidents, to 2013, the number of reported breaches just on federal computer networks — the .gov and .mils — rose from 26,942 to 46,605, according to the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team or US-CERT, which helps defend against cyberattacks.

Last year, US-CERT responded to 228,700 cyberincidents involving federal agencies, companies that run critical infrastructure like nuclear power plants, dams and transit systems, and contract partners. That’s more than double the incidents in 2009. And employees are to blame for at least half of the problems.

Last year, for example, about 21 percent of all federal breaches were traced to government workers who violated policies; 16 percent who lost devices or had them stolen; 12 percent who improperly handled sensitive information; at least 8 percent who ran or installed malicious software; and 6 percent who were enticed to share private information, according to an annual White House review.

“It is very ironic,” said Curtis, himself a cybersecurity expert who worked to provide secure networks at the Pentagon. “I was the person who had paper shredders in my house. I was a consummate data protection guy.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.