Poet and memoirist Richard Blanco’s Cuban grandmother loved him. A lot. But there were times in his childhood when she acted as if she hated him, or rather, what she feared he was. She had a whole litany of things “los hombres” – to her mind, a real man – did not do. He was not to play with his cousin’s Easy-Bake Oven or use strawberry-scented pencil erasers. When he excitedly used his own money to buy a latch hook rug kit for an elementary school class activity, she snatched it away. It was, in her viewpoint, “too gay” and she was trying to scare him straight. “What’s next, ballet?” she asked him.

“And then she gets me a leather kit,” Blanco said, laughing over coffee in the Old Port this fall. It was the kind of crafting kit a small boy could use to make, say, a cowboy lariat worthy of the Marlboro Man. “It’s amazing I don’t have a leather fetish.”

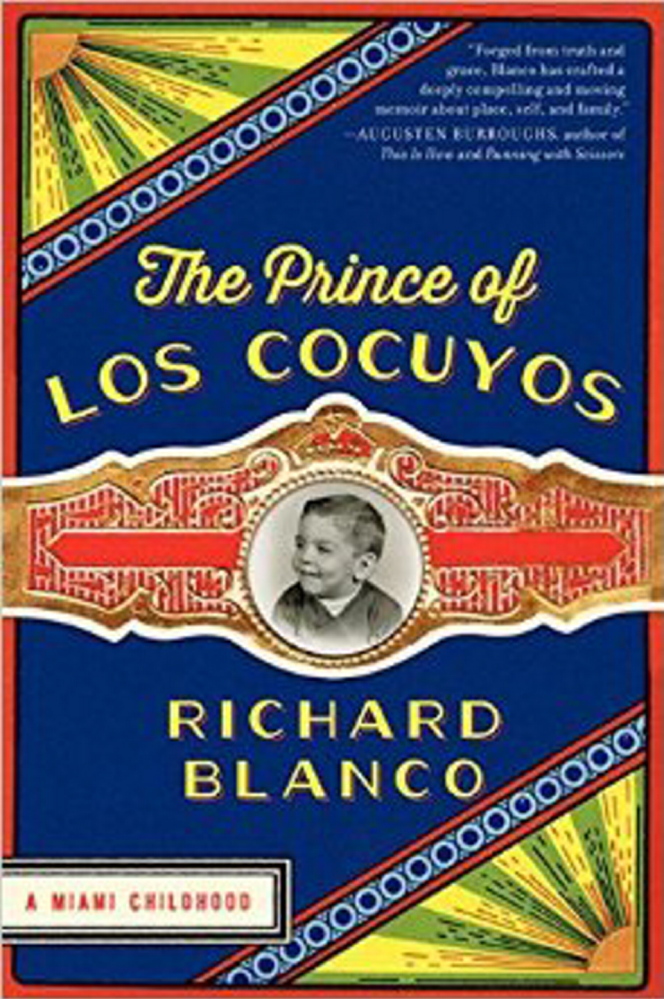

The Bethel resident tells these stories in his moving, often very funny memoir, “The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood,” published in October by Ecco/Harper Collins. The book takes Blanco, best known as the inaugural poet at President Obama’s swearing in ceremony in 2013, from his earliest memories to the cusp of adulthood, a teenager poised to embark on a journey to self-acceptance as a gay man.

Yet, it took Blanco years to shake off the impact of his grandmother’s discerning and often unforgiving gaze. She looked inside this boy they called little Riqui and believed she could make him grow into a manly man who would marry and give her great-grandchildren. Even in her dotage, when he was still closeted, she tried to convince one of his girlfriends to marry him, offering the woman $10,000 to seal the deal. But his abuela was clever like a fox.

“Just to mess with her, we said okay, and then she laid it out,” Blanco said. “It was like, 3K when you get married, and 2K for every kid.”

Her rule, spoken in less than perfect English, was: “It’s better to be it and not look like it, then to look like it even if you not it.”

Those instructions were so powerful that Blanco says, even if he tries to be effeminate, he can’t. “You don’t want to see me in drag; it’s scary,” he said. In childhood, it was easy to connect to his feminine side, but she drove it out of him. “I just feel like I can’t go there,” he said. “It has been so eradicated.”

LITTLE BIG WOMAN

Yet Blanco laughs a lot when remembering his grandmother: she was the life of the party, everybody loved her, she was fun. “She drank, she was 4 and half feet tall and had boobs out to here,” he said, gesturing far in front of his chest. Not long after the family left Cuba, she started a door-to-door resale business, marking up items, and came up with a $10,000 down payment for a house in Miami. She brokered a deal with her son and daughter-in-law to let her live with them rent free for the next 20 years. And then she went into the bookie business.

“I always say my grandmother was the dumbest and the smartest woman I ever met,” Blanco said. “And the stingiest and the most generous. She was a complex character, a businesswoman like you only read about.”

The big surprise of this memoir, which Blanco hopes will be the first in a series, is that his grandmother remains an endearing character. The bigot who berated him for his tastes and inclinations was also there to pick him up after school or drop him off at baseball practice while his parents were working at the family business, a neighborhood bodega. “I grew up completely cared for,” he said. “In some ways my grandparents were more influential in my life than my parents.”

He never discovered the source of her homophobia. “I expect that, as with all homophobia, there is always something behind the curtain, you know?” Blanco said. But it played a crucial role in his choice of careers; in the face of her disapproval he became increasingly self-conscious and withdrawn, developing observational skills he believed were vital to his survival.

“She made me an introvert, which made me a writer indirectly,” he said.

Writing “The Prince of los Cocuyos” was a way to process their relationship. “The book let me hate her, understand her, forgive her and love her in that order,” Blanco said.

LONG FORM, NEW FORM

The book’s publication capitalizes on the sudden public interest in Blanco, but the manuscript was already underway when he was chosen to read at the Obama inauguration. His memoir project started just as a “creative curiosity,” he said.

“I wanted to see how my life would look without line breaks,” he said. Poetry gave him the emotional outline to tell his story, whereas prose helped him unpack his own psychology. Writing the memoir was a pleasure, editing it less so. Book editors tend to point out things like a car that is red in one chapter and maroon in another. “In poetry, you’re like who cares?” Blanco said, laughing. To create a reliable narrator he had to “put on my engineering hat” (his previous career) and make spreadsheets for the family history.

But his broader goal with “The Prince of los Cocuyos” is that people use it as a mirror, whether it is young adult readers struggling as “little Riqui” did, or their parents or loved ones. Even someone like his grandmother (“Everyone has someone in their life like my grandmother, right?”).

“It’s for everyone who has ever felt out of place,” Blanco said. “And, at the end of the day, it’s about hope and overcoming obstacles, regardless of the funny grandmother or the evil grandmother, however you see her. To borrow on the whole campaign, it does get better.”

He’d like to write a sequel of sorts to the memoir, focusing on his relationship with Cuba and debunking some of the myths about the country, a place he said is often overly romanticized. “Old hippies look at Cuba as the country that gave the finger to the man. It’s like, dude, that is so not that anymore,” Blanco said. Or, the country has been unfairly demonized as a threat to national security, he said. “It’s such an old rhetoric on both sides of the 90 miles.”

Although he didn’t visit until he was in his 20s, Cuba had always shaped his identity, particularly through his mother. She’d left her whole family behind and never saw her mother again. (Blanco was born in Spain in 1968, shortly before the family arrived in the United States; his father named him after Richard Nixon.)

“There was always this sense of loneliness and sacrifice,” he said of his mother. Fear of loss made her a control freak, he said, and in some ways, he’s assumed that mantle. “I am always prepared,” he said. In keeping, he arrived at the interview absolutely on time, itinerary in hand. “That’s partly why I studied engineering, because the engineer’s job is to figure out what can possibly go wrong and fix it before it gets broken.”

A DOOR OPENS

With the announcement on Dec. 17 that President Obama is opening the door to diplomatic relations with Cuba after more than 50 years, Blanco may find increased interest in that still-unfinished memoir as more people come and go between the countries.

“I’m just trying to catch my breath,” Blanco said during a phone interview the day the story broke. He’d already tried to call his mother three times without reaching her. How would life be different with that Iron Curtain at least halfway open (the trade embargo still stands, unless Congress votes to lift it)? Cuba loomed large in his formative years because it was forbidden. “It was this imaginary, wonderful place that we came from that we couldn’t go to,” he said.

As the door to diplomatic relations opens, Blanco said the main concerns for Cubans and Cuban Americans he knows is that things move slowly and carefully. No McDonald’s popping up in quaint Havana, for instance. “We want to make sure that whatever changes take place that Cuba remains Cuba,” he said.

But there are sudden, exciting possibilities that the arts exchange he’d been working on with Cuban writers for next fall will suddenly become much easier to arrange or that his mother might be able to retire there. Whole families may be reunited, thanks to the action of the president Richard Blanco wrote a poem for.

He and his longtime partner, Mark Neveu, whom he plans to marry soon (“we’re plotting between February and May”) visited the White House to meet Obama the spring after the inauguration – things were too busy on Inauguration Day for them to talk – and found him to be the president-next-door. They spoke of poetry, health care and trust.

Blanco asked how the president knew to have faith in him. What if the relative unknown had suddenly switched gears in the spotlight and read a poem by say, Allen Ginsberg? “He said something kind of tender and interesting,” Blanco said, “which was, ‘We find that in situations like this, people rise to the occasion.’ “

In retrospect, Blanco wonders whether he could connect the dots between his selection as inaugural poet, that visit and the surprise of Obama’s sudden move to open doors between the two countries.

“It just feels great to think that I was, in some way, any way, indirectly involved,” he said.

His grandmother, who showed acceptance in her eyes, if not in words, on her deathbed, would be pleased.

Staff writer Mary Pols can be contacted at 791-6456 or at:

mpols@pressherald.com

Twitter: @marypols

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.