Diane Bowie Zaitlin’s “Undercurrents” is billed as “a contemporary approach to the ancient medium of encaustic in combination with drawing, written word, and antique papers.”

Well, it might be all that, but it’s a painting show. The seminal flag paintings that launched Jasper Johns to the top of the art world were encaustic. Willem de Kooning painted over newspapers. And since Cubism, words and collage have been common elements of painting.

The discussion of multimedia approaches opens some interesting philosophical doors, but Zaitlin’s work presents itself as much more focused on the experience of painting. There is a great deal of compelling abstract painting happening in Maine, but as different modes of contemporary art (photography among others) jockey for the wall and floor space of Maine’s galleries, sometimes it’s hard to see this new wave of abstraction.

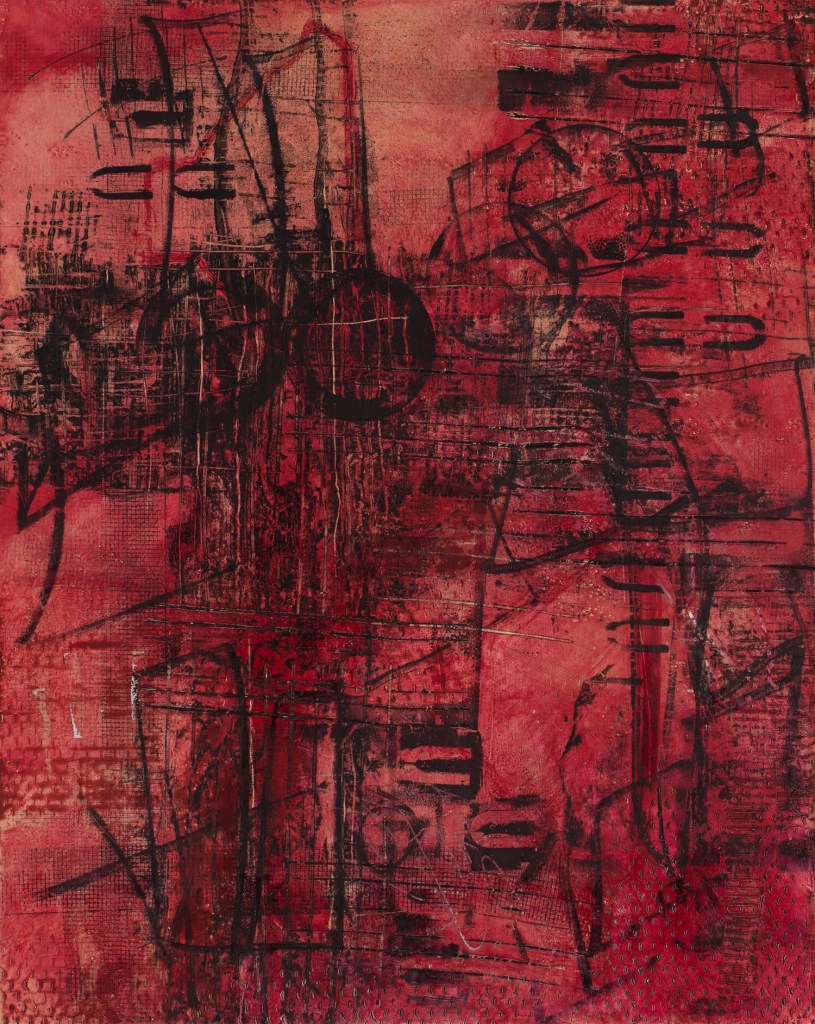

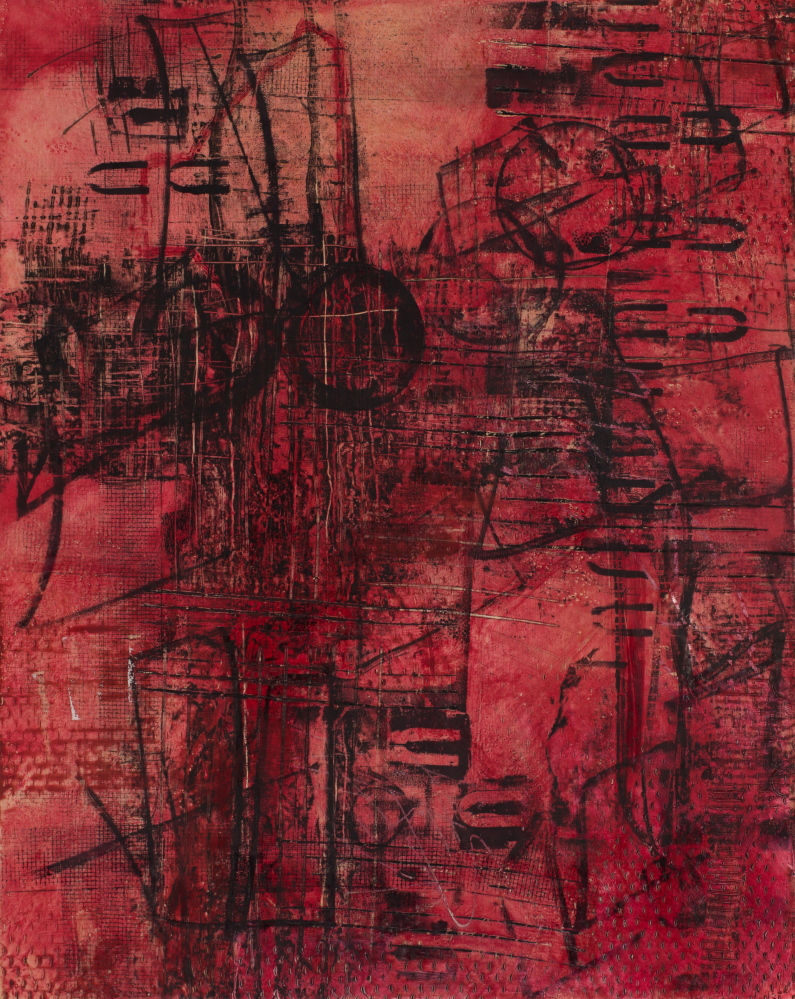

Zaitlin’s paintings are not big, but they are large in presence. Their colors tend to be bold and their surfaces feature highly energized marks that run over, through and under the patches of red, blue, white, cream, yellow and green.

One series acts reductive (minimal) insofar as it features vertical groups of pods from the catalpa tree (known vernacularly as the “Indian Bean” tree) placed on the natural encaustic surface, a creamy blend of 85 percent beeswax with tree resin. These natural works are unapologetically luscious. However spare they may be, their indulgent flavoring moves them quite far from true minimalism.

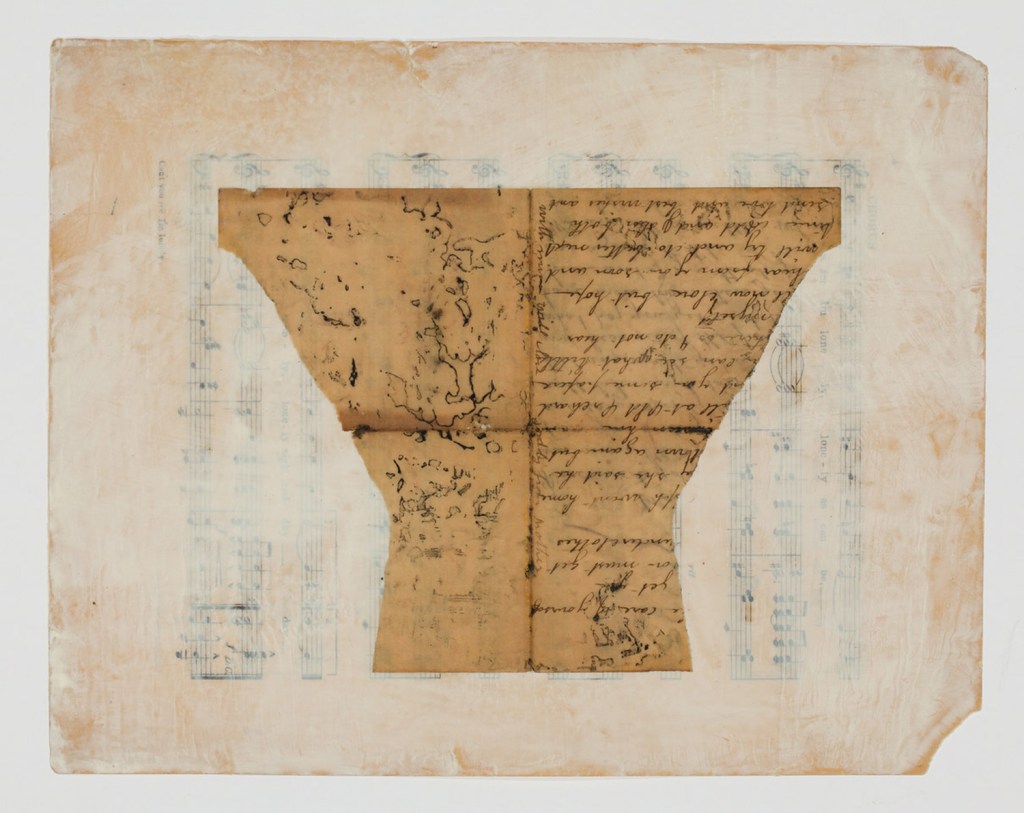

The inherent sense of underlying collage drives the logic of “Undercurrents.” Most of Zaitlin’s paintings have a topological feel that causes the viewer to mentally lay them down flat. (An exception that proves the rule is the atmospheric green “Bird Song” hung next to the map-based “Body of Water.”) This seems to happen for several reasons. To begin, a few of the works have been painted over collaged maps, and this literal topological orientation is compelling enough for us to project it onto the works in general. Enough of them look like maps that, when maps actually appear, we orient them all as maps. This is reinforced by the solidity and opacity of the most common pigments as well as the naturally formed surfaces of the paintings which – scarred, scored, burned, melted and boiled – look like geologic textures of the earth seen from space. (This is the literal approach of local encaustic painter Rick Green, for example.) Zaitlin reinforces this topography connection with her penchant for map-like design. Moreover, when collage elements appear, instead of reading like wall signage (or the held-up-vertically-by-the-reader newspapers of cubism), they are often hand-written texts on intimate objects – personal letters or hand-labeled baggage tags – that refer to the horizontal orientation of when they were written. Consequently, we mentally push Zaitlin’s paintings back down to their hypothetical horizontal orientation.

This horizontal reorienting, authored by modernist painting more than a century ago, is a radical shift from traditional painting in which the picture plane was treated like a window. Zaitlin reinforces this path through midcentury modernism with wizened, included texts that blend just the right balance of nostalgia with the here and now (the here-and-now quality being a defining hallmark of post-war abstraction).

Zaitlin presents a this-moment sense through her dedicated sensualism and clear vocabulary of post-war American painting. Yet, ironically, this opens the door to terms important to the context of “Undercurrents.” Post-war America took over as the cultural center of Western society after a war in which Europe’s erudition and cultural refinement was seen to have failed to safeguard Western values. Indeed, the most heinous crime of the war was the Holocaust, a word that shares its root with encaustic painting. “Encaustic” comes from the Greek word “enkaustikos,” which means to “burn in.” “Holocaust” (from the Greek “hólos,” “whole” and “kaustós,” “burn”) was a type of burnt offering from the Jewish Bible (“olah” in Hebrew texts) made by Noah or Abraham when he sacrificed a ram in place of his son, Isaac.

Seen in this light, the violent marks and scoring of the wax surfaces begin to create a subtle post-war Jewish cultural narrative. Reinforced by the geological logic of history as referenced by the scorched and melted surfaces, this cultural narrative also engages in the philosophical modeling of cultural modernism as a traumatic wound, such as in philosopher Theodor Adorno’s 1956 “Die Wund Heine” (“The Heine Wound”), an essay about the painful reception of art that was hugely influential on post-war criticism.

While I defaulted to indulging in Zaitlin’s work as lusciously exquisite abstract craft, by the time I had reached the 44th painting on the first floor, called “Crimson,” I came to see it as flayed flesh, a wound. Depending on how you follow the show, it’s either the first or last work on the main floor, since it greets viewers on the left as they enter the hallway gallery (following our etymology theme, “left,” in Latin is “sinister” and carries ideas of sin and wrong to the left in painterly places such as Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper”). Moreover, Zaitlin’s “Crimson” feels like a brilliant tip-of-the-hat to George Wardlaw’s gorgeous and similarly powerful series of monochromatic plague paintings that had hung in the same space just a few months before.

To be honest, I didn’t come to read “Undercurrents” as so brutal and brainy until having visited several times. Zaitlin is an exquisite painter so it’s easy to enjoy her works simply as beautiful paintings (and that’s a good thing). Frankly, if not for the site of the exhibition (and the works’ titles), it might be impossible to read the work as Judaica. This is hardly a flaw. Rather, it’s testament that Zaitlin’s work succeeds on many levels.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.