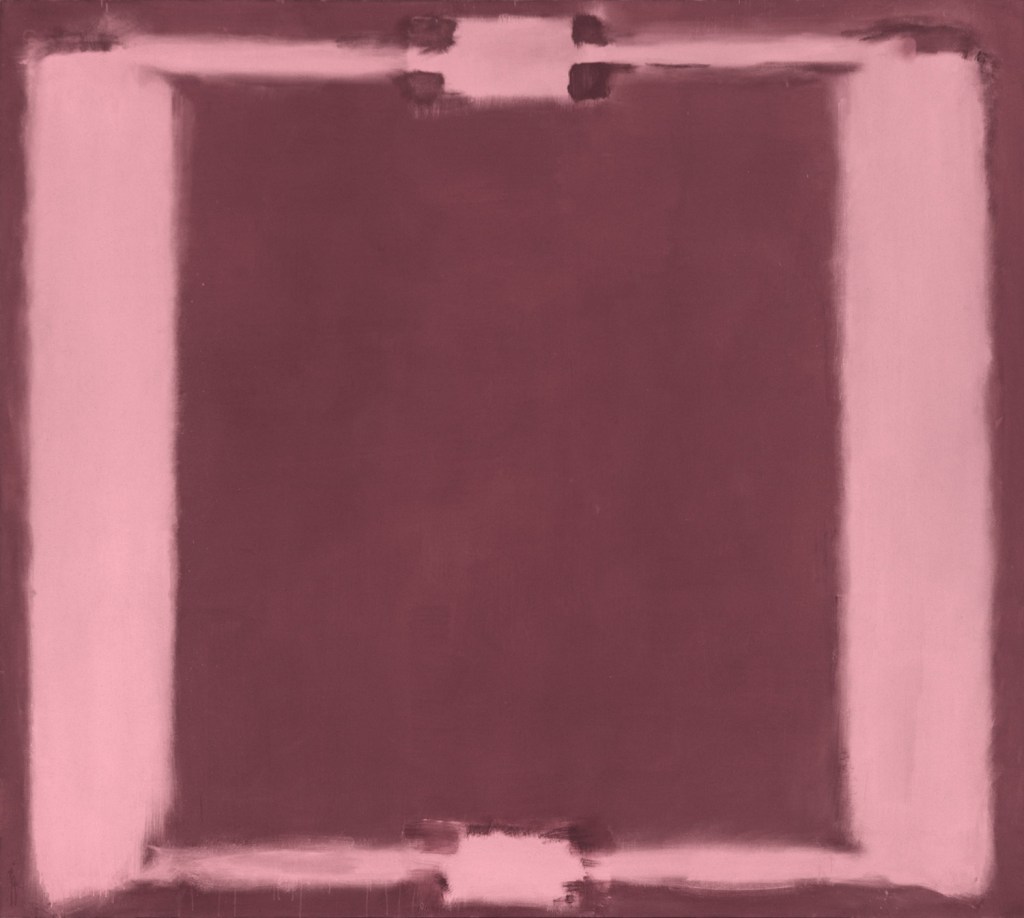

Colby College Museum of Art director Sharon Corwin called the museum’s new acquisition – Joan Mitchell’s 1968 “Chamrousse” – “the best example of abstract expressionism in Maine.”

Depending on your point of view, Corwin’s comment might make you think about the qualities of the Mitchell – or that there is a paucity of worthy abstract expressionism in Maine.

Or both.

For the record, Mitchell’s giant four-panel “La Vie en Rose” is one of my very few obligatory stops when I visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art and yet I think “Chamrousse” is a better painting.

So, no Pinocchios for Corwin.

Or, try this for context: Last year, one of Mitchell’s paintings from the 1960s set a record for the price paid at auction for a work by a female artist.

When it comes to art, however, outrageous fortune seems to invite slings and arrows. No doubt many readers will scoff at the auction comment because of a conflicted myth of postwar American art I call the “sell-out paradox.” Paintings proved they were important to Americans by drawing huge prices and while many artists desire that kind of success (and/or rely on the myth to justify their identities as artists), many despise those who achieve it.

On February 25, 1970, Mark Rothko was found dead in his studio. He had overdosed on anti-depressants and razor-slashed his wrists. It was the same day his Seagram murals arrived at London’s Tate Gallery. Rothko had become very successful – so successful that his erstwhile friends had turned on him, jealously naming him a sellout. Clifford Still had even asked Rothko to return the paintings he had given to Rothko in friendship over the years.

I am glad I did not know the story behind the paintings when I saw them in the Tate in 1987. It was a life-changing experience for me – powerful, transportive, humbling and undeniable.

I hadn’t told my 13-year-old son anything about my experience with Rothko, and yet they exerted their gravity on him when we visited the exhibition of murals in the new Harvard Art Museums building. I had to pull him away.

I waited until the play “Red” finished its run at Portland Stage before writing about the Rothko commission works at Harvard. It’s a two-person play about Rothko as he debates the meaning and relevance of his work with a younger painter who works as his studio assistant.

“Red” is poison largely because it’s such an excellent play: If you see it before you experience Rothko’s art for yourself, it will likely be forever stained by the overdetermined debates and essentially cartoonish portrait-of-the-artist-as-a-stage-character wrought by John Logan – the writer of “Hugo,” “The Gladiator,” “The Last Samurai,” “Rango,” “Skyfall” and so many other hits. Logan doesn’t lie per se, but he misrepresents Rothko and the content of his work. It is easy, after all, to steamroll something that can’t speak up for itself.

Logan circumvents the fact Rothko was his own chief salesman – and that consequently much of what he said must be construed as marketing speech. Logan renders a brilliant artist into a caricature by strangling a few glib pronouncements into catchphrases.

The way to experience a Rothko is to give yourself a few minutes alone with the work – away from discourses, dialogues or lectures. Just get your body comfortable, face the paintings, free your mind and wait.

The experience isn’t contrived, and it’s not fiction that tautologically “proves” some Howard Roark’s superiority. You experience your own perceptions, emotions and humanity – the very stuff that makes you feel real.

“Red” doesn’t count on the Harvard show, and that’s why I refused to write about it until it had left Portland. In the play, we see Rothko make murals for a commission and then return the money on principle and keep the paintings. (Those very murals executed for the Four Seasons – but not delivered – were the paintings I saw in the Tate Gallery.) The audience might leave thinking Rothko was too principled for a commission, but the Harvard murals were a commission as well.

Logan does put some good ideas into play, such as the cyclical distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian – standard fare of Art History 101 typically discussed as the ebb and flow between the classically ordered “Renaissance” and the chaotically emotional “Baroque.” But theories, philosophies, cocktail comments and even lists of inspirations are not the same thing as content.

After all, does learning personal things about Logan (e.g., he’s 53 and graduated from Northwestern University) help understand “Hugo” or “Red?” I don’t think so. And I don’t think learning about Rothko’s personal tribulations will help you unfurl the content of his paintings. This is why I think seeing “Red” before you spend time with Rothko’s work will interrupt your experience – not enhance it.

Rothko’s work is popular for the very same reason it is hard to discuss. It’s not a treatise and it’s not a rebus. It’s musical in the sense that your experience happens over time and without words. As you acclimate to the simple forms and the dense and subtle colors of the Harvard murals, for example, it becomes less clear which is the form and which is the background. You move back and forth between involving your body in your perception and leaving it behind as irrelevant – and it is this destabilized phenomenological (bodily awareness) sensation that makes it clear why people with a proclivity towards spiritual explanations can have what they describe as powerful, mystical experiences.

However you describe your experience of Rothko’s work, the experience itself is not verbal. It is not theater. It is not a linear narrative or a rebus with a fixed path.

What I get from “Red” is that we need to think harder about how we talk about art in Maine – particularly abstract painting. We need to stop confusing intention, inspiration and biography with content: That’s like ordering dinner and being served a printed recipe or a description of the food.

And while you can send back an unacceptable entree, you cannot un-experience a play.

Pedantically echoing Hamlet’s opening line (“Who’s there?”),”Red” opens with Rothko staring at an imagined painting on the fourth wall and the line “What do you see?” The entire play could be described as the slow-motion strangulation of that line. It marks the middle and leaves us (in a fitting echo of Ionesco’s absurdist “The Bald Soprano”) dangling with it again at the end… with Rothko robust, riveted and repeated.

To see, or not to see – that is the question.

The answer: Yes!

Go to Harvard and see the Rothkos. From Portland, it’s not much farther than driving to Colby to see “Chamrousse” as well as incredible new works by Carl Andre, Martin Puryear and Julie Merhetu. And definitely, go see them as well. As to whether you should see “Red,” at least wait until after you go to the Tate.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.