Less than 42 years after the Wright Brothers first flew an airplane, the United States of America dropped a nuclear bomb from the sky onto the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

How many people killed by the bomb is the subject of political debate, but what is clear is that in the moments, hours and days following the blast utter confusion reigned on the ground. Not only had the communications and governmental infrastructure been vaporized, but in the flash of a moment, the inconceivably terrible future had arrived.

The age of nuclear war is the unspoken context for “Past Futures: Science Fiction, Space Travel, and Postwar Art of the Americas,” at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The exhibition focusing on artistic images of the future from the 1940s through the 1970s – the Cold War Era – closes today, and if you haven’t seen it, you should. “Past Futures” is the insightful, entertaining and exciting parting gift (a present) of Sarah Montross, the museum’s now erstwhile Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow.

The pervasive Latin American perspective may seem arbitrary, but a little Cold War reconsideration of the Good Neighbor Policy and the unfurling Cuba problem sufficiently hint that our “close” friends had good reason to worry about the roiling pugilistic tensions between the Super Powers. The effect of the shifted perspective is palpable and compelling when you encounter the work. The otherness of the Spanish-language American cultures, in particular, helps us step out of our Cold War American corner.

“Past Futures” features work roughly gravitating to four prevailing themes: aliens, space travel, time travel and the question of whether we are looking toward a utopian or dystopian reality.

Beyond the exciting design of the show and the impressive depth of the academic endeavor, what gives “Past Futures” its true heft is the art. (Let’s keep in mind that academic exhibitions are often more like a set of illustrations for a book than an exhibition documented by its accompanying catalog. Still, if you miss this show, you should definitely check out the fantastic catalog.)

The works in “Past Futures” are fascinating, and many of them are extremely rare treats. Moreover, they represent an exquisite blend of big names and unforgettable discoveries.

The artists we immediately recognize build a strong context for the show. The seven Roberto Matta (Chilean, 1911-2002) paintings in the exhibition’s first room alone are enough to make this an internationally noteworthy show. Here we see Matta’s paintings develop from colorful but angsty surreal landscapes – like his 1941 “Rain: Mexico” – into his dazzling (as in spots before your eyes) monumental space-station-esque “Life is affected” painted the year the Soviet Union’s Sputnik went into orbit – and induced fear in most of America.

Joining Matta in the first room are several powerfully unnerving sky-oriented totemic images by the great Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991).

“Past Futures” is a surprisingly apt setting for Robert Smithson (American, 1938-1973). Most impressive are his time-travel piece “Incidents of Mirror-Travel,” shot at Mayan sites, and his uncannily timely 1966 “Proposal for a Monument at Antarctica,” a ghostly negative Photostat (which means this piece, that belongs to the Met, is rarely on view) of people erecting a Minecraft-like structure, oddly, by hand in the white shadows of ghostly ships.

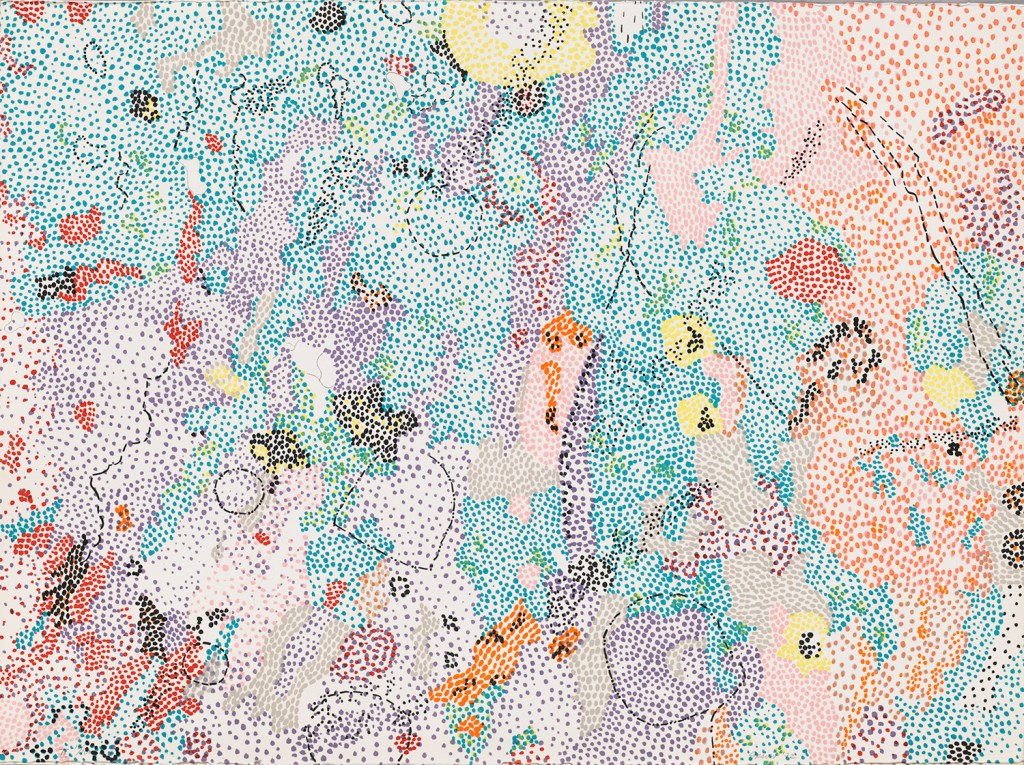

Nancy Graves’ (American, 1939-1995) suite of 10 pointillist-like topographic lithographs comprises an oddly effervescent high point of the show. They make for an oddly compelling marriage of data with decorative strategies.

There is not even remotely the space here to address the major accomplishment of “Past Futures” – the re-framing of a large and truly exciting group of visionary artists whose work appears to be coming into focus (in the United States, at least) only now.

A gossamer ink drawing by Emilio Renart (Argentine, 1925-1991) is like a landscape of magnetic fields, but above all it’s a thing of stunning beauty that dovetails with the concept-oriented art being produced locally by artists like Clint Fulkerson, Lauren Fensterstock and Cyndy Davis.

The work that most obviously stands out, however, is by artists whose construction-oriented conceptualism aligns with current international trends. In “Past Futures,” they provide a kind of blueprint for the future with a DIY accessibility. And this is the crux of the show: In “Past Futures,” the future isn’t just a place where anything is possible – it’s where we can achieve the impossible. It’s an American trope, after all, that the future belongs to visionaries like Benjamin Franklin, Steve Jobs or Buckminster Fuller. It’s not only the artists and the sci-fi authors (there is a fascinating collection of Spanish-language sci-fi displayed), but also the people who have the blueprints and the ideas, which includes us – the audience.

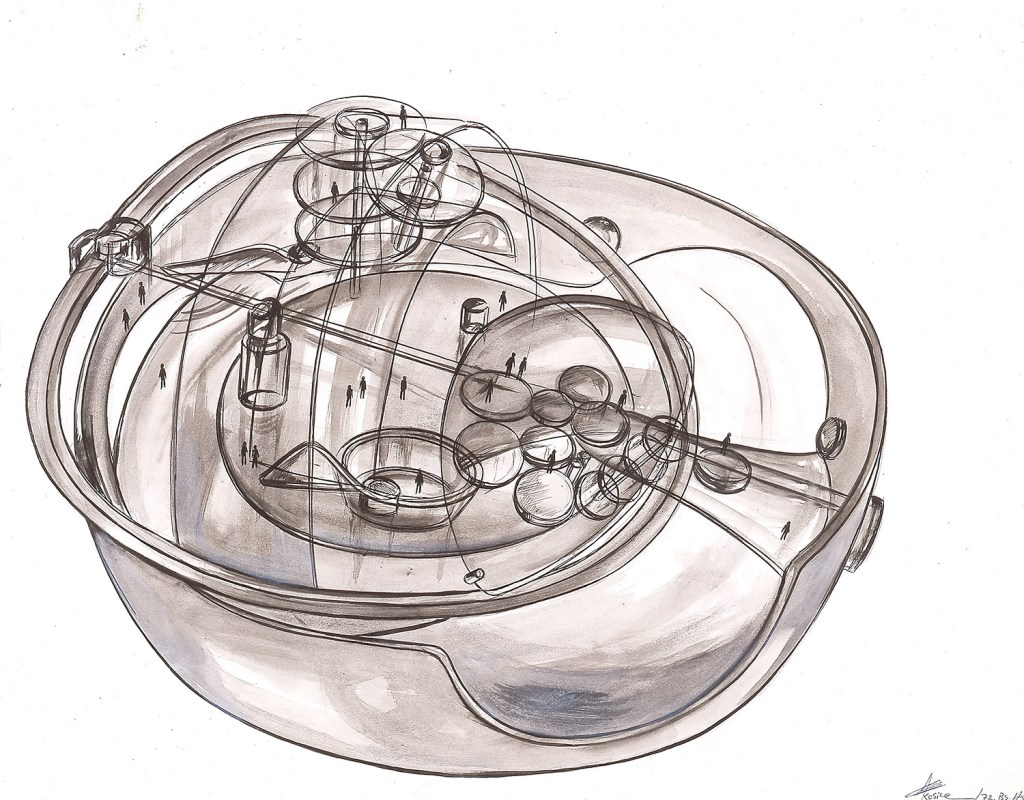

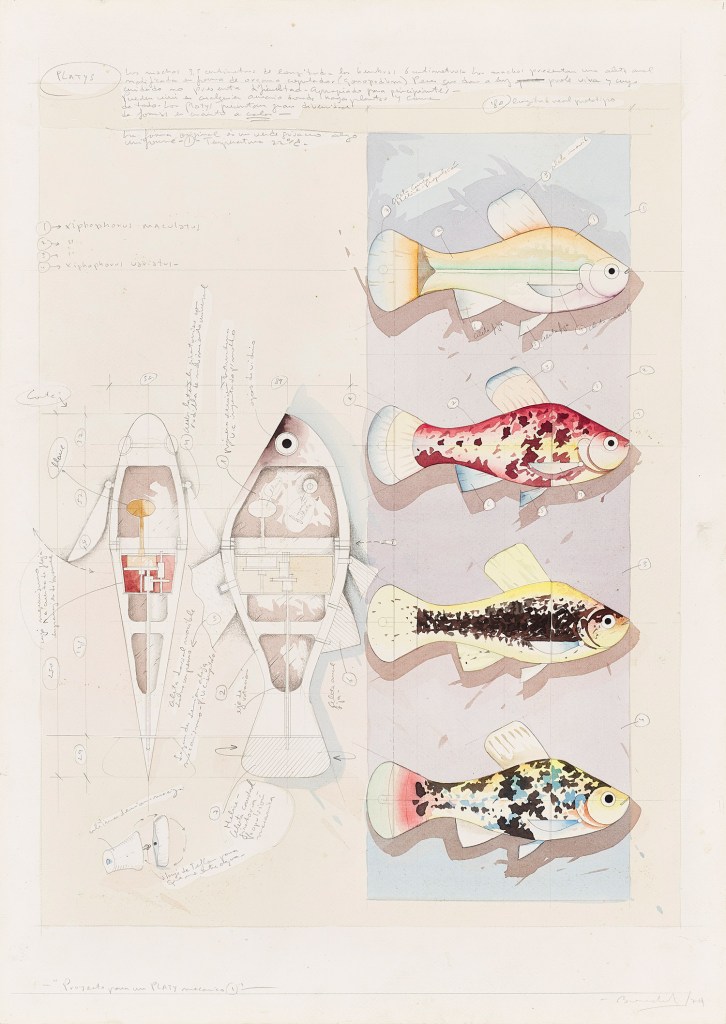

The greatest discoveries for me were a suite of artists who aren’t yet well known but deserve to be. They are led by Argentine Gyula Kosice (1924-) whose utopian “Hydrospatial City” appears not only in fantastic drawings, but as a cooler Plexiglas model suspended by monofilament. Another Argentine, Luis Fernando Benedit (1937-2011) impresses with construction drawings for portable animal habitats, but transcends even himself with designs for a clockwork fish (a roughy?).

You may have seen Raquel Forner’s (Argentine, 1902-1988) work before, but her 1971 painting “Astronaut and witnesses, televised” is a paradigm-shifting presence in this show.

Two Chilean artists, Juan Downey (1940-1993) and Enrique Castro-Cio (1937-1992) should be superstars. Castro-Cio’s 1963 “Blossoming Mesoamerica,” uses blueprint logic in a way that matches the heady diagram approach of much of the artworld’s smartest, savviest and hippest drawing. It looks like an inner ear’s well-labeled transformation into a sentient being. Downey sees the seeds of God alternately in the images of timely technology and the cosmos. (God’s nostrils, for example, are shown un-ironically as bean-bag chairs.)

So what is the future? Just a few miles up the road from Bowdoin is Bath Iron Works where, for the first time, weaponized lasers were mounted in Arleigh Burke class nuclear destroyers just last year. Or is the future when my five-year old son stopped in front of a non-electronic grocery store door, waiting patiently for it to open itself. When I was his age, we had just put a man on the moon, the Cold War was raging and I was a dedicated fan of Star Trek – the actual source for the idea of those sliding doors.

“Past Futures” boldly goes where no one has gone before – making the case that the harder we work to imagine the future, the more likely we are to bring it about. No one, after all, is going to build it if we don’t.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.