CENTENNIAL, Colo. — It was an agonizing decision. Should prosecutors be allowed to show a paralyzed mother a photo of her slain 6-year-old daughter while she testified in the Colorado theater shooting trial? Or would the image make her break down in tears and unfairly bias jurors against the gunman, James Holmes?

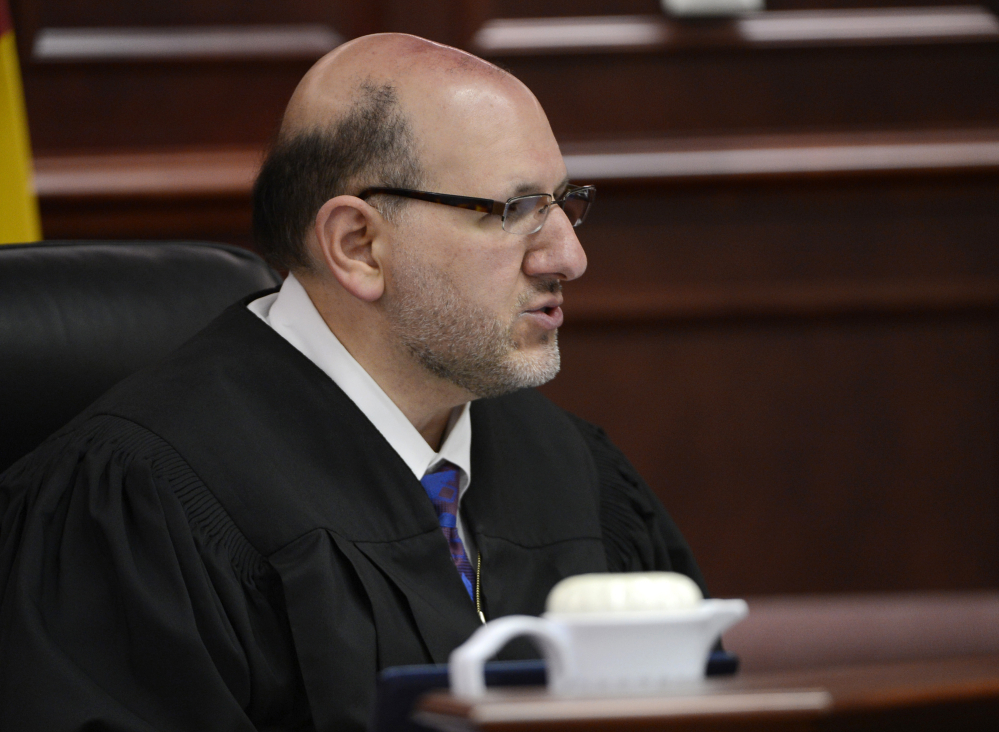

Judge Carlos A. Samour Jr. mulled the question overnight and then tried to achieve some kind of balance.

“I’m going to allow the people to show it,” Samour said the next day, “but, literally, for three seconds.”

The ruling highlights the daily difficulty the judge faces in balancing the raw emotion of the trial with the need to be dispassionate. It’s a monumental case for the 48-year-old Salvadorian immigrant, who still speaks in a heavy accent that softens his sometimes strict and stern demeanor.

Legal observers say he has handled the massive death penalty case with care and foresight, all while keeping an eye out for jurors and victims.

“There is a tremendous stress and strain on everyone in that courtroom, and that most definitely includes the judge,” said Denver defense attorney Craig Silverman, a former prosecutor. “This judge has performed masterfully under the most difficult of circumstances. He’s kept control of the courtroom.”

The rare mass shooting trial has brought big challenges. Vast media coverage of the July 20, 2012, attack and its far-reaching impact prompted the judge to summon 9,000 prospective jurors in one of the largest and most complicated selection processes in U.S. history.

He winnowed that pool down to 24, an unusually large number, knowing he would need more alternates. When he chose to dismiss five jurors for exposure to news reports or family emergencies, he refused to let it derail the case.

And then there are dilemmas like the kindergarten graduation photo of Veronica Moser-Sullivan, the youngest of 12 who died in the crowded theater. The decision to allow it was one of dozens of delicate choices Samour has had to make during the trial, which has been a struggle between prosecutors and defense attorneys over how much pain and gore is too much.

The stakes are high. Any significant error on Samour’s part could risk having the case overturned on appeal, forcing everyone to go through it all again.

“The defendant has a constitutional right to a fair trial. The defendant does not have a constitutional right to a sanitized trial,” Samour said after Holmes’ lawyers asked him to bar photos showing blood on theater seats and aisles. Yet he wouldn’t let prosecutors play a video of police cars shuttling dying victims into a hospital ambulance bay and their bloodied bodies on gurneys. That, he said, went too far.

“Judges are humans, and you really have to sit in on a case like this to fully appreciate how hard that makes the judge’s job,” said Terry Maroney, a professor at Vanderbilt Law School who has studied the impact of judges’ emotions on criminal cases. “At the end of the day, you do want a human being in charge of these proceedings, someone who knows how to handle the welter of emotions.”

If he has his own powerful feelings when he steps down from the bench, Samour doesn’t show it. But he spends nights and weekends researching case law and writing rulings, a sign of how the trial has preoccupied him.

Through a court spokesman, Samour declined to comment. A longstanding gag order keeps those involved from talking about the case.

His family fled El Salvador for the United States in 1979, when he was just 13 and his home country was roiled by civil war. In Colorado, he graduated from Columbine High School 16 years before the shootings that left 12 students and a teacher dead. He earned his law degree from the University of Denver and worked in private practice before becoming a prosecutor in the Denver district attorney’s office.

He became a district court judge in 2007. Before the theater shooting, he was best known for ordering a reluctant prosecutor to file sexual assault charges against two men in 2009.

Carol Chambers, then the Arapahoe County district attorney, thought the evidence was too weak. But Samour ruled that Chambers’ decision was “unjustifiable, arbitrary, capricious and without reasonable excuse.”

The Colorado Court of Appeals overturned Samour’s order, saying prosecutors have discretion to decide what cases to pursue. But it left an impact.

“What he did in that case was really courageous,” said Baine Kerr, the attorney who represented the victim. “He’s not afraid to make difficult decisions. He’s ideally suited for the Aurora theater case. He’s got the perfect combination of compassion for crime victims and really sharp legal intelligence that make for the perfect judicial temperament.”

Before the shooting trial began, defense attorneys sought to have him replaced, calling him hostile, biased and disparaging toward them. Samour denied the request. His terse language was him being straightforward, he said, not biased.

His decisions sometimes end with a lecture. When defense attorneys asked for a mistrial days into a prosecution expert’s testimony, he interrupted their argument.

“What can I do now?” Samour asked. “You should have objected before he took the stand.”

The attorney continued to press him.

“No,” he said. “We’re done.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.