WHITEFIELD — A national shortage of organic milk – the result of changing American diets – is fueling interest in Maine among dairy processors eager to increase supplies and meet growing demand.

As many dairy farms in the West struggle under drought conditions that have dried up pasturelands, Maine is seen as promising territory. Its abundance of water and land gives the state an advantage because organic dairy cows spend much of their lives outdoors, grazing in grass pastures.

Steve Getz, who manages the milk supply in most of New England for Organic Valley, sees Maine’s potential whenever he drives through the state.

“You go past field after field after field of grasslands,” he said. “Let’s put the land to use.”

He’s not the only one thinking that way.

Wisconsin-based Organic Valley and New Hampshire-based yogurt-maker Stonyfield Farm are running campaigns in Maine to persuade conventional dairy farmers to switch to organic farming methods and to help new farmers start organic dairy farms. More than a dozen farms have already made the switch or started the process in the past year.

The push for organic milk comes as conventional dairy farmers are once again facing tough times. The prices Maine farmers get for their milk – which reached an all-time high last September at $2.25 a gallon – dropped to $1.45 a gallon in May. Organic dairies are now paying farms about twice as much. Those costs are carried over to consumers, who pay twice as much for organic milk as conventional milk.

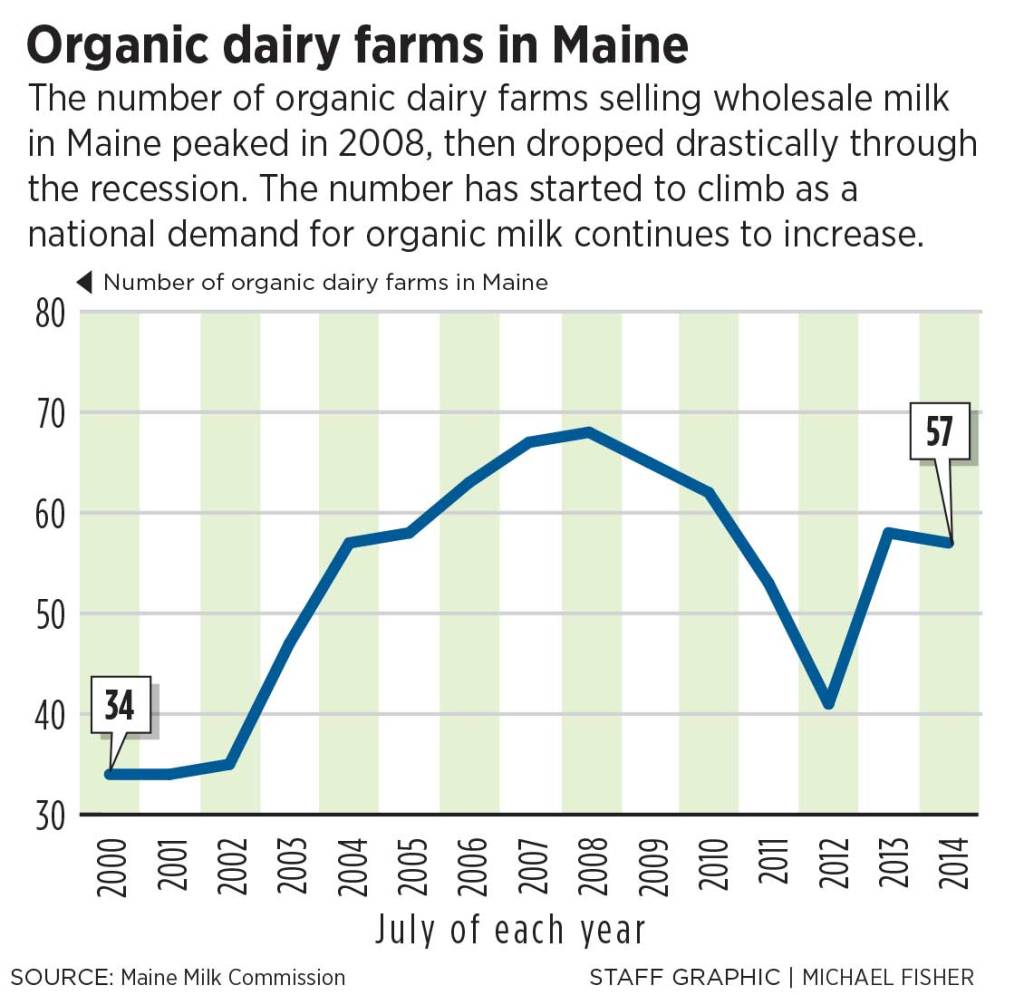

The new interest in Maine also represents a turnaround from 2009, when softening sales of organic milk caused H.P. Hood to drop eight organic farms in Washington and Aroostook counties and to cut production quotas at 14 other organic producers. The other organic processors in the state – Organic Valley, Stonyfield and Colorado-based Horizon Organic, would not take on the abandoned farmers because there was an oversupply of organic milk at the time.

But the market has changed. Internal research from Organic Valley shows that consumers – led by health- and environment-conscious mothers of young children – are driving up demand for organic dairy products. Sales of organic milk nationally increased 10 percent in 2014 over the previous year while conventional milk sales nationwide fell by nearly 4 percent, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data. In nine years, annual sales of organic dairy products in the United States have grown from 1 billion pounds in 2006 to nearly 2.5 billion pounds in 2014.

In Maine, the trends look a lot different. Sales of organic milk peaked in 2007 at 4.4 million pounds, fell steadily through 2013 and then rose in 2014, to 3.9 million pounds, according to the Maine Milk Commission.

For milk to be labeled organic, cows must be fed organic feed, not administered antibiotics or growth hormones and have unrestricted year-round access to the outdoors. Cows must graze on pasture for the full length of the local grazing season and get the majority of their food from natural grass. Although farmers use modern milking equipment, their farms operate much like they did a century ago before many dairy farms became industrialized in efforts to increase productivity.

In modern conventional farms, cows typically remain indoors and eat food that is brought to them. Their diet is also different – more grain and less grass. Grain provides more concentrated energy, but the natural diet of cows consists of plants that can be grazed. The animals’ complicated four-part stomach helps them to slowly digest relatively large amounts of grass.

BOOSTING SUPPLIES

Organic Valley and Stonyfield are taking different approaches to boosting milk supplies.

Getz last summer moved from Vermont to Waterville so he could focus on Organic Valley’s recruitment efforts in Maine, particularly in Aroostook County, where dairy farming is a growing business because of an influx of Amish families.

Getz has picked up 12 farms in the past year, including eight farms in Aroostook County, bringing the total number of Organic Valley farms in the state to 40.

Organic Valley, with annual sales nearing $1 billion, is a cooperative of 1,800 farmers nationally. The co-op’s farmers in Maine last summer voted to support the expansion by subsidizing the cost of sending a milk tanker to the state’s northernmost county. The farmers believe that rebuilding Maine’s dairy industry protects their own livelihoods by sustaining farming infrastructure, such as grain providers and large-animal veterinarians, said Jeff Bragg, who converted his dairy farm in Sidney to organic 11 years ago.

“If it helps agriculture, it helps us all,” said Bragg, who now operates the largest organic dairy farm in the state, with 160 milking cows.

Stonyfield, which produces most of its yogurt in its plant in Londonderry, New Hampshire, is investing in training new farmers. Its parent company, French food and beverage maker Danone, has given a $1.7 million grant to Wolfe’s Neck Farm in Freeport to create a program that teaches young adults the agricultural and business skills they need to start their own organic dairy farms.

The program’s first student arrived at the farm last week to begin a two-year apprenticeship. Three others will arrive this summer. The farm is building a herd of 60 certified-organic heifers so it can begin selling organic milk to Stonyfield.

Stonyfield also is offering to help conventional farmers convert to organic, and to help existing organic dairy farmers increase their herds.

The yogurt-maker now has milk supply contracts with three farms in Maine and expects to sign up three to four additional farms over the next six months, said Kyle Thygesen, a farmer relationship manager for Stonyfield who covers the Northeast.

Thygesen said the company’s biggest concern is to make sure that dairy farmers nearing retirement age can find people to take over their farms and to secure the long-term supply of organic milk in the region for its New Hampshire plant.

His message to struggling conventional dairy farms is that there are profits in organic.

“There is an opportunity,” he said. “There is always opportunity when there is demand.”

PROMISING STABILITY

The pitch that Getz and Thygesen make to farmers is that they can run their businesses more predictably because their milk prices are based on annual contracts.

The organic processors maintain the price premium for organic milk by limiting supply when there’s less demand. They do this by not signing contracts with new farmers, which is what happened in Maine in 2009.

Conventional farms have no limits on how much milk they produce, so their revenues can spike when milk prices are high. But conventional milk prices, which are regulated by the government and are affected by a variety of economic factors, fluctuate month to month, making it difficult for conventional farms to mange cash flow. When the price goes down, they often add cows to sell more milk. That’s why conventional farms keep growing in size.

When dairy farms are paid less for their milk than it costs to produce it, they get a check from the state that comes from a pool of money funded by Maine dairies. Both organic and conventional farmers are part of that system.

Michael Moody, 42, who owns an organic farm in Whitefield with 55 milking cows, said the stability of organic milk prices allows him to take greater risks when making decisions about investing in the farm, such as the new barn he plans to build.

Letting cows feed on pastures on their own is less expensive and less labor-intensive than buying grain and hauling feed to the barn, he said. “One of the things we like about grazing is we can make a lot of money off it,” he said. “It’s making farming viable.”

Moody has been helping Conor MacDonald, 25, and Alexis Gareau, 31, who two months ago started a new dairy farm in the Knox County town of Washington, where they have 14 milking cows. MacDonald, a former Green Beret who served two years in Afghanistan, said organic methods and the pricing structure make it easier to start a new farm with a smaller herd.

“You can start small and keep things simple with organic, and do things right and pay attention to the cows and the land more,” he said.

It’s expensive to convert a conventional farm to an organic one, however. That’s because it takes a farmer one to three years to win organic certification. In the meantime, the farmer must pay the higher operating costs of running an organic farm while receiving the lower pay of conventional milk.

Organic farms have higher operational costs. Organic grain, which must be transported to Maine from the Midwest and Canada, costs roughly twice as much as the grain used at conventional dairies.

The three organic companies buying milk in Maine all truck the milk out of state for processing because there is no large-scale commercial processing plant for organic milk in Maine.

Bragg said that many Maine farmers won’t make the switch to organic because they want their milk to be processed in Maine, such as at Oakhurst, which for years has promoted Maine milk and has won the loyalty of many farmers.

MULTIPLE CHALLENGES

While drought conditions in California, which produces 20 percent of the nation’s organic milk, have played a factor in limiting supply, the bigger issue is that a generation of farmers is retiring, and it’s hard to recruit new farmers to replace them, Getz said. Starting a new farm is a challenge because it can cost more than $1 million to buy land, barns, cows and equipment for a large farm.

“They can go out of business quicker than you can start another farm – that’s the challenge we face,” he said.

The owners of organic dairy farms are under the same economic and demographic pressures faced by conventional farms. The majority of Maine dairy farmers are over age 55, according to 2012 U.S. Census data. While there is growing interest in Maine agriculture among young people, few are entering the dairy business because of the large upfront capital costs.

Jeremiah Smith, 59, a fourth-generation dairy farmer in Monmouth, is a conventional farmer who is contemplating switching to organic. His farm is struggling now because of low prices. He said he hopes that switching to organic would allow the farm to make a profit.

The main obstacle, he said, is the cost of installing new fencing in pastures and rebuilding his barn so he can give his milking cows access to the outdoors in winter without mixing them up with his dry cows. The conversion costs are as much as $100,000 – about a quarter of his gross annual income as a conventional farmer.

Another problem: His cows would also have to cross a busy Route 132 to reach new pastures.

“There are challenges no matter if you stay conventional or convert,” he said. “It’s a matter of choosing which challenges you want to face.”

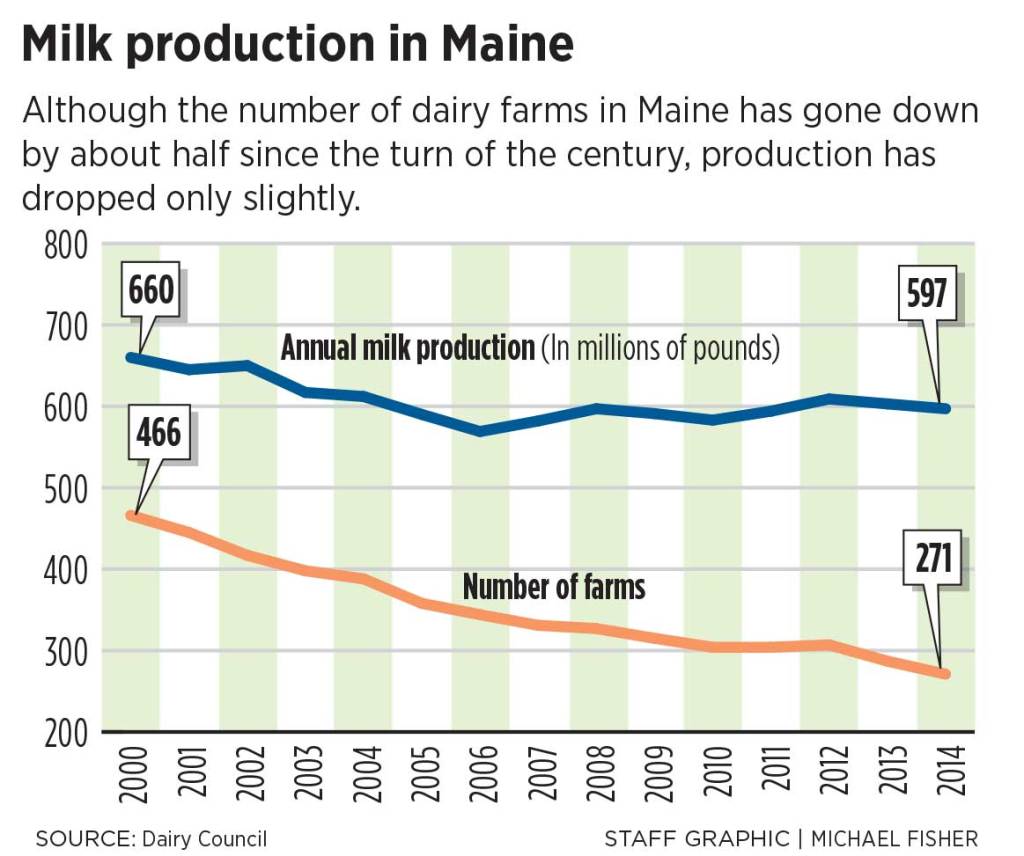

Today more than 20 percent of Maine’s dairy farms produce organic milk, up from 7 percent 15 years ago.

From 2000 to 2014, the total number of dairy farms in Maine fell 42 percent from 466 to 271, while the number of organic dairy farms increased 68 percent, from 34 to 57, according to the Maine Milk Commission. Still, conventional farms, which are typically larger and more efficient, produce 93 percent of the total milk in the state.

The organic sector suffered a serious setback when Falmouth-based Maine’s Own Organic Milk, known as MOO Milk, shut down a year ago. The partially farmer-owned company was founded in 2010 at a time when the organic dairy market was soft. Ten farmers who had been dropped by Hood Inc. banded together to create the Maine-branded organic milk company, but the underfunded collaborative ran into trouble when it couldn’t afford to replace problematic carton-filling equipment that had been donated.

All but one of the 12 farms that were delivering milk at the time the company shut down are still in business. Those farms now all have contracts to deliver milk for Organic Valley, Stonyfield and Horizon.

In Maine’s northernmost county, the number of dairy farms is increasing. That’s because Amish farmers are moving to The County and starting farms and grazing cows on fields that are too small for large-scale potato farms. Over the past seven years, the number of Amish dairy farms has increased from zero to about a dozen, said Vaughn Chase, 59, an organic dairy farmer in Mapleton. All are conventional farms, but five have begun the process to convert to organic.

While the organic market is strong, farmers need to maintain access to both organic and conventional markets to be secure, said Rommy Haines, director of the Aroostook County Farm Bureau. He said the farmers there understand that they must continue to produce enough conventional and organic milk to fill the two milk trucks that travel there, one operated by Organic Valley and the other by Massachusetts-based Agri-Mark, a processor of conventional milk.

If one milk truck stopped making the long drive because it lost too many customers, the farmers would face economic disaster if the remaining truck also pulled out, he said.

“You end up like the MOO Milk farmers – without a market.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story