WESTBROOK — Rick Knight wrestled with the joy of seeing the boys who once played Little League baseball for him – and a certain sadness.

Those boys were in their early 20s now, reunited briefly on a warm, sun-lit Saturday while being honored at the city’s Little League complex on Bridge Street.

“How big they’ve grown,” said Knight, who still manages youth baseball. “They looked so much older. Wow, it seemed like only yesterday.”

This week, eight teams from the United States and eight more from around the world will gather in South Williamsport, Pennsylvania, for the Little League Baseball World Series.

Ten years ago, Maine had a rare representative in the World Series: the Westbrook Little League All-Stars. Those boys, age 11 to 13, were one of only three teams from the state to have ever played in the event, now in its 69th year.

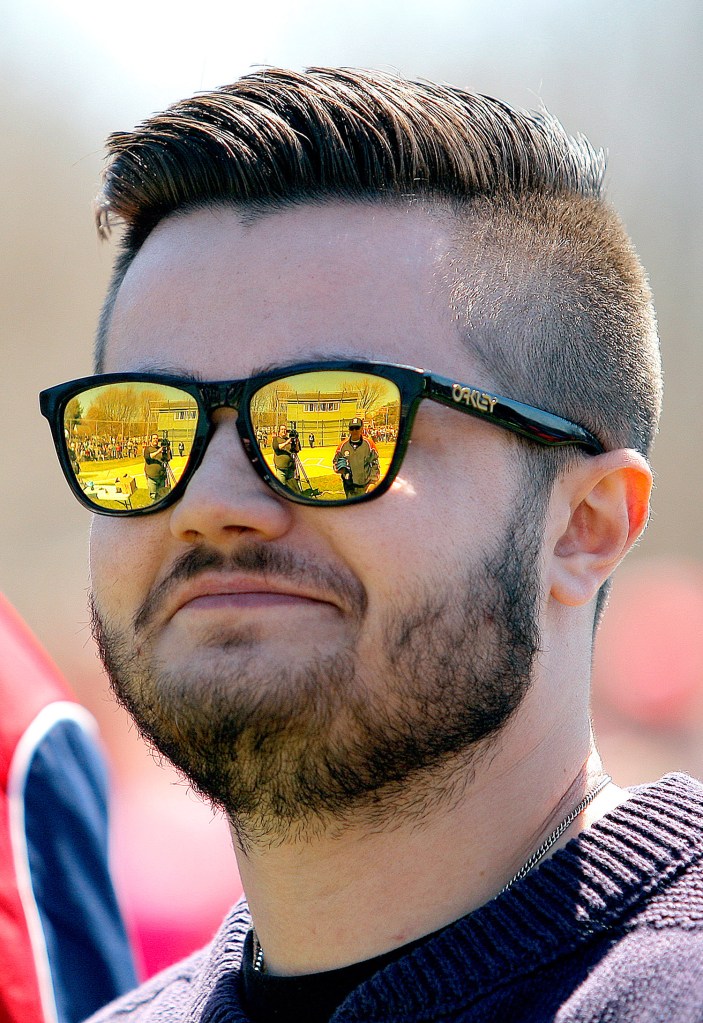

“I don’t know where the 10 years went,” said Nick Finocchiaro, the team’s catcher and also a pitcher. “It was crazy. We were being recognized for something we did 10 years ago, and we’re just starting our lives now.”

They did more than win tournament games during that magical August. They won the hearts of Mainers far beyond the city’s borders with their pluck and their perseverance.

“Even today there are conversations in the coffee shop about that team,” said Lou Lampron, a fixture in Westbrook community sports for decades. “That summer was a special time in Westbrook. Any time, at any level, you reach the World Series it’s special. I don’t care if it’s the Red Sox or a team of 12-year-olds.”

Much like Boston’s historic comeback against the New York Yankees to reach the 2004 World Series 10 months earlier, Westbrook mounted an improbable comeback to win the New England Regional and earn a trip to Pennsylvania.

Westbrook didn’t win the World Series, but somehow, that didn’t seem to matter. Maine had already embraced them. Only the Suburban Little League of Portland in 1951 and Augusta East in 1971 had preceded Westbrook in the World Series. Neither of the other teams had the benefit of playing in front of ESPN cameras.

“No one was thinking about people back in Maine watching us on ESPN or paying attention to us,” said Tommy Lemay, the second baseman. “We didn’t know.”

But the players were reminded by Knight that they weren’t just representing Westbrook. Coming home, they realized what he meant.

“It wasn’t until we got off our turnpike exit coming home to Westbrook and saw the police car waiting to escort our bus,” Lemay said.

Upon their return, they made media appearances in Portland and Bangor, were recognized by shoppers at the Maine Mall and took a trip to Augusta that included meeting Gov. John Baldacci and shooting pool on the Blaine House billiard table.

UNLIKELY ODDS

How Westbrook reached the World Series was the hook that grabbed Mainers. The team lost its first three games in pool play in the New England Regional in Bristol, Connecticut.

Lose one more, and their summer of playing baseball together would be over. Lose, and the dream of reaching the World Series would remain forever a fantasy. Even a victory in the next game might not be good enough, according to tournament rules. The players listened quietly as Knight, their manager, explained the scenarios that had to happen involving other games.

“We thought we had no hope,” said Knight. “I was preparing them for the fact we were probably going home. But I misunderstood one of the tiebreakers of pool play. The third tiebreaker was for least amount of runs allowed. I thought it was for most runs scored.”

Westbrook still had to win its next game and Knight played his ace card. He reminded them that the Red Sox had lost their first three games to the Yankees in the 2004 American League Championship Series. The Red Sox had to win every next game to reach the World Series. Westbrook could do the same.

“We didn’t have any stars,” Finocchiaro said. “We understood the dynamics of our team. We had to be a team to win. We picked each other up.”

Westbrook won its next game, beating Rhode Island, 3-0. Finocchiaro pitched and struck out 12. He hit three singles and drove in three runs. He pitched again in the championship game, again against Rhode Island. Mike Boothby, the Westbrook third baseman who batted eighth in the lineup, hit a home run and drove in four runs. Westbrook won, 7-2.

‘WE PROVED PEOPLE WRONG’

The next day, they all were on the bus for the trip to Pennsylvania and the World Series. Westbrook lost its first game, 3-2 to a team from Louisiana. It lost its second game, 7-3, after California rallied to score five times in the bottom of the fifth inning. Westbrook won its last game in the tournament beating Kentucky, 3-2.

“When I think back, it’s all about how much fun we had,” said Zach Collett, who played second and third base. “All of us. It wasn’t about myself. We just really clicked. I loved playing baseball with my teammates.”

Their time together, the players say, was like the best summer camp they ever could have attended. They were away from their parents, some for the first time, and with their friends. They slept in the same dorm room, ate together, hung out at the pool or in the big game room together and played the game they loved.

“You lost track of the days,” said Sean Murphy, a pitcher and outfielder. “I will forever remember the camaraderie.”

They won’t forget Knight, either. He was 53 then and recently had left his position in management for Verizon. The 2005 All-Star squad wasn’t his first team or his last. This year’s Westbrook Little League All-Star team reached the state tournament.

“Rick was great at teaching and coaching,” said Lemay. “He was stern, and if we ever started to lose focus, he got us back on track. We were the team that could afford playing loose. There was no pressure from Rick, no pressure from our parents.”

Lemay won’t forget a scene he and his teammates and their parents witnessed immediately after California had rallied late in the game to beat Westbrook. Players and parents meet under a large tent before the players head back to their dorms. Some parents of California players berated their manager. How could he permit a team from Maine to take the lead?

“(The parents) were angry they weren’t able to beat us by 10 runs,” said Lemay. “They thought they were better than us. Like we can’t play baseball in Maine. We proved people wrong.”

HONORED AT FENWAY

That summer was crowned by an invitation from the Red Sox to come to Fenway Park, meet the players and be introduced to the crowd before the game. Each player was presented with a Red Sox jersey with their name and Little League number on the back.

“It was all a surreal experience,” said Reid Coulombe, then a 4-foot-10 outfielder who, with the equally diminutive Jarred Martin, came up with key plays on the field and comic relief off. Coulombe was the outfielder who was designated to recite the Little League pledge before games. Knight frequently chose Coulombe to accompany him for interviews. He was not shy.

At Fenway, Coulombe, with his teammates, made sure to get as many autographs as he could. He waited for Jason Varitek. “It’s for my mom. She loves you.”

The Westbrook players were to run onto the field to their positions for the introductions, standing next to Red Sox players. Coulombe, the left fielder, ran to join Manny Ramirez, his favorite player. Joey Royer, his Westbrook teammate, ran with him.

“I kept repeating two things: don’t pee yourself, don’t embarrass yourself.”

Knight and the Westbrook coaches, Harold Bettney and Don Meserve, stood at home plate. Finocchiaro and Lemay, who caught when Finocchiaro pitched, talked easily with Varitek. “The National Anthem was about to start,” said Knight. “Jason leaned over and told the boys it was time to pay attention to the flag. They stood a little straighter.”

Before the seventh inning started, Murphy and Lemay stood in the new seating area on top of the Green Monster. Below them Manny had finished his warm-up throws. An adult yelled for Manny to throw the ball to him. Manny obliged but the ball glanced off the man’s hands and into Murphy’s grasp. It was too sweet.

Hours before, Murphy had asked David Ortiz for his autograph, giving Big Papi his baseball card and a Sharpie marker. When Murphy got the card back he discovered his Sharpie had run out of ink and his chance for an autograph was gone. He was upset.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

After 2005, many of the players went on to the Babe Ruth World Series and played on Westbrook High teams that went to the Western Maine Class A playoffs year after year.

Of the 12, Royer and Collett played NCAA Division II baseball at the University of New Haven. Success followed them to that level. Royer developed into an effective starting pitcher for the Chargers. Collett, the team’s starting first baseman and run producer, hit third in the lineup. Royer and Collett were accounting majors and graduated this spring.

Murphy hurt his pitching arm in high school, had surgery, and couldn’t find success again on the mound. This fall he plans to attend the University of Maine-Farmington, get his degree, and follow his parents into teaching. Now about 6-foot-4, he hopes to play for UMF’s basketball team.

Finocchiaro lives in the Boston area, working in computer software, helping his employer write programs for Trident submarine missile systems. He’ll forever remember the home run he it in Westbrook’s first game at the LLWS. It was his mother’s birthday and her reaction was caught by ESPN.

Lemay has applied for a position with the same company that hired Finocchiaro. Lemay and Coulombe both graduated from the University of Rhode Island.

Lemay was the avid Yankees fan on the Westbrook team. His mom is a school teacher and gets more wear out of the Red Sox jersey presented to her son and his teammates at Fenway Park. She wears it to school on jersey days.

Coulombe, who has helped his older brother Andrew coach a junior American Legion baseball team, is now a personal trainer in the Portland area building a client base. He has grown and is no longer little Reid. His sidekick, Jarred Martin, is an Aviation Electrician’s Mate in the U.S. Navy, stationed in California.

Mike Mowatt Jr. and Mike Boothby both hit home runs in the New England tournament and the World Series. Both entered the work force after high school.

Twins Jake and Zach Gardiner went to St. Joseph’s College in nearby Standish. Along with Murphy, the brothers coached baseball in the Westbrook school system. Mitchell Chipman, who frequently batted behind Finocchiaro and could play in the outfield and infield, is a student at the University of Southern Maine.

None of the 12 has truly drifted away from the lives of the others.

Rick Knight has returned to the World Series several times, most recently two or three years ago. He and a friend got to the U.S. championship game early but the grandstands were full. He went to the ticket window anyway. The tickets are free but fans need one for a seat.

Sorry, Knight was told. No more tickets. Knight was wearing his 2005 World Series cap. The designs vary from year to year but the colors don’t. Someone else in the ticket office moved to the window and spoke to Knight.

“You were the manager of the team from Maine, weren’t you. How many tickets do you want?”

Knight and his friend got two, right behind home plate.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story