Is there a class of human more unsettling than the teenage girl? Her moods are unpredictable, her powers of attraction alarming. As Stacy Schiff amply shows in “The Witches,” it was ever thus – at least since 1692, when two Puritan girls in Salem Village, Mass., via a series of thrashes and moans and accusations of witchcraft, incited a campaign of terror that led to the execution of 19 women and men.

Why the girls’ elders did not order them to behave – why instead the law saw the devil’s work in even the most pious community members – can be explained by the persecution complex from which the Puritans suffered, the drab toil of their lives finding relief in the theater that was the witch trials. Men of ambition, notably the minister and pamphleteer Cotton Mather, employed the devil as a convenient tool with which to amass power. If dozens of innocents died along the way, well, who was to say they were innocent?

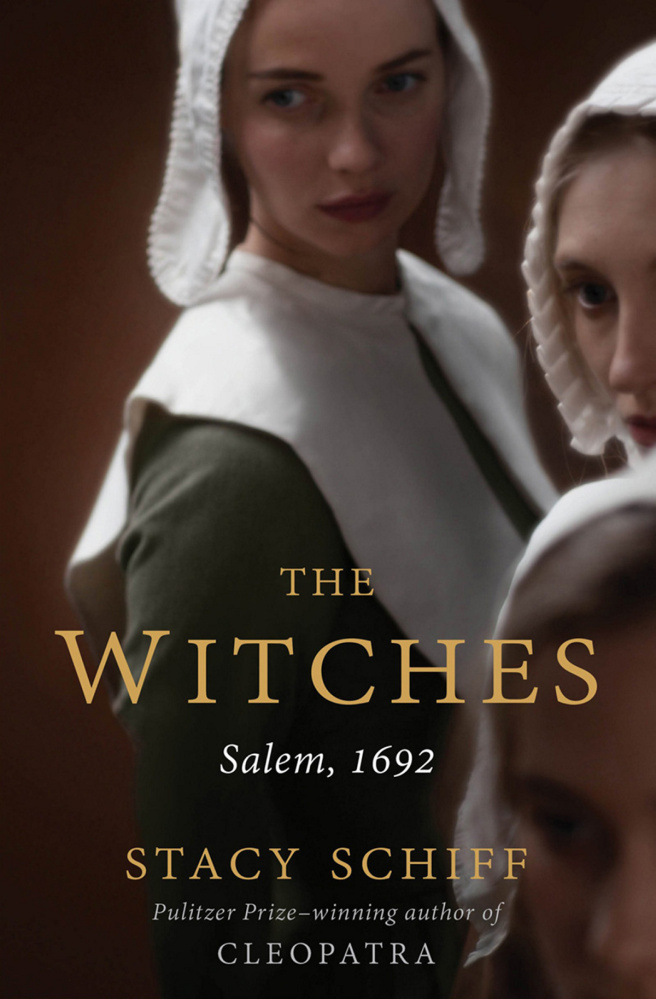

More than 300 years later, we are still examining the wounds, which Schiff, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Cleopatra” and an indefatigable researcher, offers in compulsively readable form.

The trouble began in January 1692, in the home of village minister Samuel Parris. Parris was a busybody and not well liked, but the pinches and pinpricks of which his daughter Betty and niece Abigail complained won the household new standing. The girls’ afflictions grew in proportion to the limelight; they claimed they’d been bewitched, and they started naming names.

That such behavior might have been rebellion (“Instructed not to fidget, well-mannered, well-behaved Betty and Abigail writhed,” Schiff writes) occurred to too few citizens. The girls were not seen as naughty but enchanted – and thus relieved of their chores. Their celebrity (and leisure) did not go unnoticed.

“Hysteria is contagious and attention addictive,” writes Schiff of the other young women (and, soon, citizens of all ages and both sexes) who took to shrieking and fainting and showing off bite marks.

Clergy, neighbors and the town’s doctor (who diagnosed “the evil hand”) were mesmerized by the accounts of ravishment, of townspeople doing the devil’s work. The Puritans might be under England’s thumb; they might suffer from a “lavish New England envy” that made them eager if often powerless to take their brethren down a peg. But they knew how to handle witches. Within weeks, dozens of the accused were packed into a filthy, frigid jail. They were shackled in irons. They gave birth and died and went mad in what was called “a grave of the living.”

Bedlam reigned at the trials. The accusers raved and rolled and were struck “blind” when confronting those they accused. Claiming innocence was futile; only those who confessed were spared execution. The condemned were driven in carts past their jeering neighbors and hung from a gallows erected on a granite ledge, and, in one ghastly case, slowly crushed under a slab of stone. That some accusers recanted (one explained they spun their tales for “sport, they must have some sport”) only made the judges process the accused faster, executing as many as they could before the winds of history blew cold.

Which, by the fall of 1692, they did. “It was as if all simply, suddenly awoke, shaking off their strange tales, from a collective preternatural dream,” writes Schiff.

During the trials, Mather whipped the frenzy, in the form of sermons and pamphlets and political cronyism. Where he might have claimed service to God, the reader sees opportunism. Afterward, he and others expressed few misgivings about the torture and murder of innocent people. As Schiff writes, “The only brooms that played a role in the witch hunt were wielded afterward by men, to sweep the year under the carpet.”

In the book’s final sections, Schiff expertly unknots what drove the Puritans to mass delusion. The reasons are timeless. People will always be histrionic – what the Puritans called enchantment, and Freud called hysteria, is today known as conversion disorder. There will always be those whose ambition and faith drive them to destroy others. There will always be jealousy. That the 1692 Salem witch trials were an anomaly is an illusion of the vantage point; we remain fascinated because we sense in our skin (and see in the news) that the same could be happening right now.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.