Bob McLaughlin’s obsession began on a spring night in 2004 outside his home, his gaze fixed on an intense glow that hung above the hillside.

McLaughlin, an advertising writer, had just bought a house on the edge of South Pond in Warren, a two-mile stretch of water surrounded by trees just west of Route 1. Looking over the pond, he could not help but see the halogen lights looming.

“It looked like a city,” said McLaughlin, now 71. “I said, ‘That must be the prison.’ ”

His mind went straight to the only inmate he knew by name, whose case he had read about a few years earlier but had not considered since.

Dennis Dechaine, he thought. Whatever happened to Dennis Dechaine?

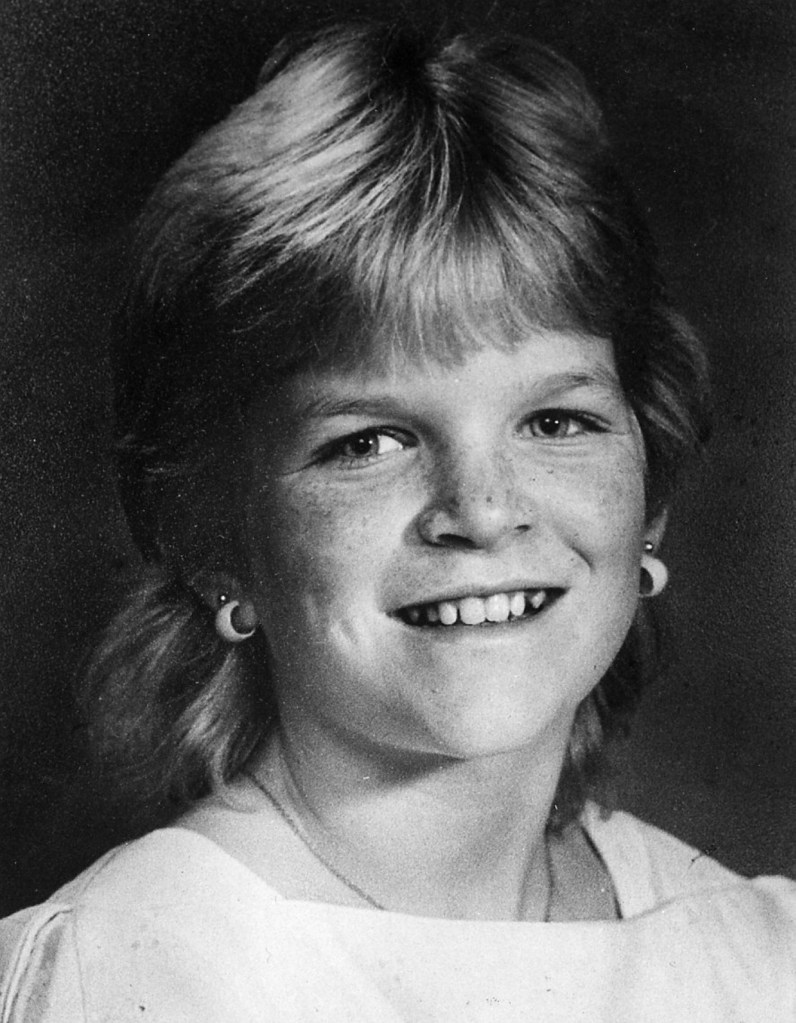

His search for answers in the state’s most infamous murder case has absorbed the better part of a decade, pulling him into the orbit of true believers who continue to dispute what police, the Maine Attorney General’s Office, a jury and the state’s highest court have decided is a matter long since settled: That one July afternoon in 1988, Dechaine abducted 12-year-old Sarah Cherry, sexually assaulted her, strangled her, stabbed her and dumped her body in the woods near the Bowdoin home where she was babysitting.

“As far as we’re concerned, it’s over, and we’d like to leave it over,” said Chris Crosman, Cherry’s stepfather, who lives in Bowdoin. “We went through 25 years of hell, and we don’t want any more.”

Sarah Cherry, 12, of Bowdoin, died in July of 1988 and Dennis Dechaine was convicted of killing her.

But the official version of events is something that McLaughlin and his cohorts cannot accept.

What drives them to follow Dechaine – and not any other case or cause – is difficult even for some of the most steadfast believers to explain. They discuss the case in the most personal ways, struggling to square their internal sense of justice with Dechaine’s conviction and failed appeals.

And while they say it will be science, not their words, that will ultimately free Dechaine, advocates also leave meetings with the prisoner enraptured and humbled – and most strikingly, even more deeply convinced that he is not a killer. A core group of perhaps a dozen keep in regular touch with one another and Dechaine, and claim an email list of several thousand.

Their persistence, now more than 27 years after the crime, is highly unusual.

“The vast majority of these cases, even cases where people are exonerated, have gone for years, if not decades, in obscurity,” said Bryce Benjet, an attorney with the Innocence Project in New York, which works to exonerate convicts, often with DNA evidence. “I think (the Dechaine case has) a very unusual dynamic, and generally only seen in the most compelling cases.”

Their work has also caught the attention of a documentary filmmaker, Richard Searls, who has spent a decade collecting footage. In December, he released a 22-minute interview with a longtime pathologist who says that Dechaine could not possibly have killed Cherry, because she died after Dechaine was already in custody – a primary contention that his supporters say proves Dechaine was innocent.

“At a deeply personal level, I’m staking everything on this,” said Bernie Huebner, 72, of Waterville, another advocate for Dechaine. “All we want is a trial where a jury can hear all the evidence. That’s why this documentary film is so important. It’s our last attempt.”

PIECES OF EVIDENCE

Sarah Cherry was 12 years old when she embarked on her first babysitting job on July 6, 1988, at the home of Jennifer Henkel. Neighbors reported hearing someone pull into Henkel’s driveway that afternoon, and hearing the family’s dogs barking.

When Henkel returned home later, Cherry was gone. In her driveway, Henkel found a receipt and a notebook with the name Dennis Dechaine on them. She called police, and they began to search for both Cherry and the 30-year-old Dechaine, who lived in Bowdoinham, around 4 p.m.

Around 8:45 p.m., Dechaine walked out of the woods on Dead River Road in Bowdoin, three miles from the Henkel home, where he was picked up by police and questioned. While he was in custody that night, police found Dechaine’s truck at the end of a logging road. Two days later, Cherry’s body was found less than 500 feet from where the truck was parked. She had been sexually assaulted with sticks, stabbed 13 times and slashed with a knife, and choked to death. A rope and a scarf from Dechaine’s truck were used to commit the crime. Police later said that Dechaine made incriminating statements during his time in custody.

At trial, Dechaine testified in his own defense. He said he went into the woods that day to inject drugs, and had trouble recalling parts of the day when Cherry went missing.

His supporters, meanwhile, have maintained that forensic evidence that was either downplayed or not fully explored at trial shows Dechaine could not possibly have committed the crime:

• No hair, fiber or blood was found on Dechaine or in his truck that could link him to Cherry.

• The knife used to stab and cut Cherry was never found, and a police dog did not find a scent of Cherry in Dechaine’s truck. A search dog tracking from the truck also did not lead to Cherry’s body.

• To prove his innocence, Dechaine has offered to pay for DNA testing of the evidence since the beginning of the case – a request that has never been granted. His willingness to submit to such testing is further proof of his innocence, his supporters believe.

The time of Cherry’s death has also been disputed. Dechaine supporters say the state’s own forensic examiner concluded that Cherry died after Dechaine was taken into police custody, a finding that wasn’t properly emphasized at trial.

Collectively, Dechaine’s supporters say they have spent thousands of hours visiting with him.

They have told Dechaine about their lives, their families, their travels, their difficulties and successes. They ask about his feelings, his life in prison and his attempts to keep himself busy and his mind intact. They fret to one another about the places Dechaine will never go, the children he will never raise, the life he will never live.

Aside from scientific evidence they contend disproves his guilt, supporters believe that the thinking, feeling person they have come to know was not capable of committing such a heinous crime, that his character is proof enough of his innocence.

Underpinning the criticism is the belief that police and prosecutors, in their rush to arrest someone and quell public fear, never considered anyone but Dechaine as a suspect – that the desire to convict him was so overriding it subverted any chance of a full and fair investigation or trial – accusations that authorities say are baseless.

All of Dechaine’s appeals for a new trial, including to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court, have been rejected.

To get a new trial, he would have to show not only that there was new, exculpatory evidence the court had not considered, but that this evidence would raise doubts about the original verdict.

“The standard in Maine is pretty darn high to get a convicted person a new trial,” said Warren Silver, who retired from the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in 2014 and who has had no role in deciding any of Dechaine’s appeals. “You have to produce some evidence to say that this is so compelling that we have to retry this case, evidence that wasn’t in front of a jury. It is a puzzling situation, why these people believe in him. He’s had a lot of due process.”

UNEXPECTED ALLIES

At the core of the group advocating for Dechaine are two people who, when they first met in 1992, had little nice to say about each other.

Carol Waltman grew up with Dechaine in Madawaska, and is among his oldest friends. Dechaine was close to Waltman’s husband and brother. Waltman, 56, was one of Dechaine’s most strident supporters during his arrest and trial. She founded a nonprofit group, Trial and Error, to draw support to Dechaine’s cause.

Three years after his conviction, Waltman took her argument for exoneration on the road. During a talk at the Unitarian Church in Brunswick, Waltman saw a man at the back of the room she sensed was in law enforcement. His name was Jim Moore, a retired agent with the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. When Waltman finished speaking, Moore approached her. He said he wanted to investigate the crime himself, to prove Waltman was wrong. He had worked with the Maine State Police for years, and believed they were a good outfit.

“He said, ‘You’re a nitwit,’ ” Waltman said. ” ‘The cops in Maine wouldn’t do something like this.’ ”

Moore’s investigation ballooned. He spent eight years plowing through thousands of pages of records, trial transcripts, police reports and handwritten notes, reinterviewing police and experts. The product of his work, a 418-page book, “Human Sacrifice,” explores in granular detail the case for Dechaine’s innocence. It concludes that he was wrongly convicted.

The book became a bible for Dechaine’s supporters, a reference resource as well as a tool to evangelize on Dechaine’s behalf.

“What I find among people in power is they don’t want to admit a mistake,” Moore said. “It would embarrass them to admit that they aren’t perfect.”

Moore keeps up with Waltman and other Dechaine defenders, but his work is largely done now. He speaks in a brisk, concise clip and is an admitted cynic – a quality he said helps him ferret out the truth. He can still rattle off facts rapid-fire, bristling sarcastically when he sees what he believes is investigatory malpractice – questions unasked, interviews never conducted, follow-ups that fell by the wayside.

But Moore is getting tired. Six months ago, his wife suggested that he may look for other ways to fill his time.

“I’ve never stayed with a case for years and years and years,” he said. “Never had to. Found out (a suspect) was guilty, and proved it, or found out he wasn’t guilty, and proved that.”

He is left to wonder whether his book – or Dechaine’s guilt – will be proven correct before he dies.

“I’m getting to a point where I don’t think I can do much more on this case,” he said. “Got to find something else to do. Something less discouraging.”

STRONG FEELINGS ABOUT JUSTICE

Moore might be ready to back away, but several others are not.

Interviews with McLaughlin and other of Dechaine’s closest supporters, all of whom have no personal connection to the case or Dechaine, suggest their interest can at least in part be traced to a deep, personalized sense of justice that was often instilled at an early age.

Huebner is a longtime teacher whose career ended in 2000, when he resisted a state law requiring that public school employees submit to fingerprinting.

“I was trying to imagine what it would actually be like. A state trooper physically taking my hand and rolling the print. I felt physically sick. I had a visceral reaction.

“There’s something almost genetic in me that wants to protect the underdog,” Huebner said.

He had a similar visceral reaction to Moore’s book – a gut-wrenching feeling that a man’s life had been ruined.

Another supporter, Genie Nakell, 74, of Portland, grew up in St. Louis, where her father owned a factory that was the first in that city to racially integrate its workforce. When she was a little girl during World War II, her family took in a Japanese college student at a time when Japanese-Americans were being rounded up for internment.

When she was a child, her father always told her, ” ‘Do what you think is fair,’ ” she said.

Already a fan of true-crime stories, Nakell picked up Moore’s book expecting to find a murderer. Instead, she came away a convert.

“I thought, ‘Oh boy, there is something really wrong with this picture,’ ” she said.

Bill Bunting of Whitefield said he could not sleep for two nights after finishing Moore’s book.

“Who can predict what cause can get under someone’s skin?” said Bunting, 70. “It’s hard to explain it.”

As with almost every Dechaine supporter interviewed, discussing the case in the abstract is difficult.

At every opportunity, supporters dive into hypotheticals, seeking to wind back the hands of time – what evidence should and shouldn’t have been admitted at trial, whose testimony they believe was massaged or manipulated by prosecutors, which attorney did what wrong.

Searls, 72, is now trying to raise enough money to fund the editing and post-production work on his untitled documentary. He is working with a Portland-based producer and editor to whittle down his voluminous footage.

He hopes his documentary will strike a nerve with audiences that have devoured the podcast “Serial” from 2014, and the more recent Netflix documentary, “Making a Murderer,” released in December.

“Maine has a certain brand – The Way Life Should Be,” Searls said. “But there is a soft underbelly here. I think there are flaws within our legal system where procedure is valued over truth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story