Years ago, while researching a book about child care in our state, this reviewer came across the following in the 1927 records of Portland’s Maine Home for Boys: “The Ladies Auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan took the boys on a picnic at Higgins Beach.”

This seems to have been the only time the Klanswomen took charge of the orphans, but the occurrence itself is no surprise to local historians.

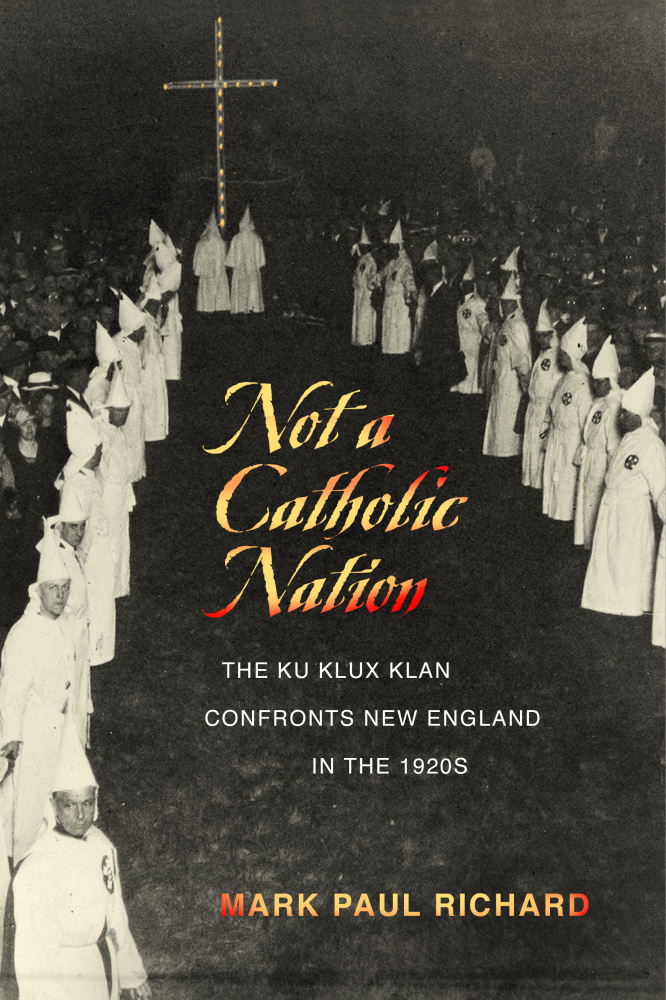

Town histories are stippled with references to the KKK in the 1920s, with photographs and even postcards of Klan events. Aside from an occasional university thesis or article, I am unaware of any book until now that describes the 1920s organization – rather, organizations – in New England.

Mark Paul Richard, a native of Lewiston and a graduate of Bowdoin College, with graduate degrees from University of Maine and Duke University, is highly qualified to write on the subject. He is a professor of history and Canadian studies at the State University of New York, Plattsburgh.

The yeasty ’20s provided conditions where numerous old-line Yankees began to fear for their livelihoods in the face of what they saw as a rise of immigrant competition. Traditional agricultural pursuits were becoming less productive and “foreigners” were taking factory jobs, filling up the cities and speaking unfamiliar languages. They were also attending non-Protestant churches.

One usually associates the KKK with the post-Civil War South, but in the wake of World War I, chapters of this loosely organized terrorist society began to appear in the Midwest and New England, led by charismatic individuals, often out for a buck.

They attracted thousands of white Protestants who felt they were losing political, religious and social ground.

This reviewer has seen estimates of up to 40,000 Maine Klansmen at the height of their power. In 1925, The Washington Post estimated 150,141 in Maine and more than 370,000 across the other New England states – staggering numbers.

Politicians, including President Calvin Coolidge and Maine Gov. Ralph Owen Brewster, failed to speak out against the group and thus won their tacit support.

When Democrat Al Smith became the first Catholic to run for president, he was defeated with help from the KKK.

Well written and well organized, “Not A Catholic Nation” is divided into 11 chapters covering the rise of the group across New England. At times, KKK leaders crossed state lines to aid one another.

Connecticut and Rhode Island were under one organizer for a time, but rival leaders, eager to accrue lucrative membership and regalia fees, were often at sword points.

While many Klansmen held hatred for Jews and blacks, the primary target of the group in New England was French Catholicism.

While a different scholar may have tended to dwell on victimization, Richard’s work highlights the strength of New England Catholics in countering the Klan – a milestone in American scholarship.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra, and their cat, Nadine.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.