Drop a lobster pot in front of a bunch of problem solvers, mix in a handful of fishermen, add some craft beer and what do you get?

The organizers of Drink Tank, a recreational think tank that calls itself a party with a purpose, were hoping for enough collaboration and creativity to make a better lobster trap.

“Everyone associates lobster with Maine, but very few people know how the whole process works,” said Drink Tank co-founder Kate Garmey. “Everybody knows the lobster trap, or has at least seen a buoy, so it’s something we’re all familiar with, but the mechanics of it are a little more mysterious. … So it is an opportunity to learn something. Once you learn all the pain points and all the issues that lobstermen have, it’s really interesting to think about, ‘How could we make that better?'”

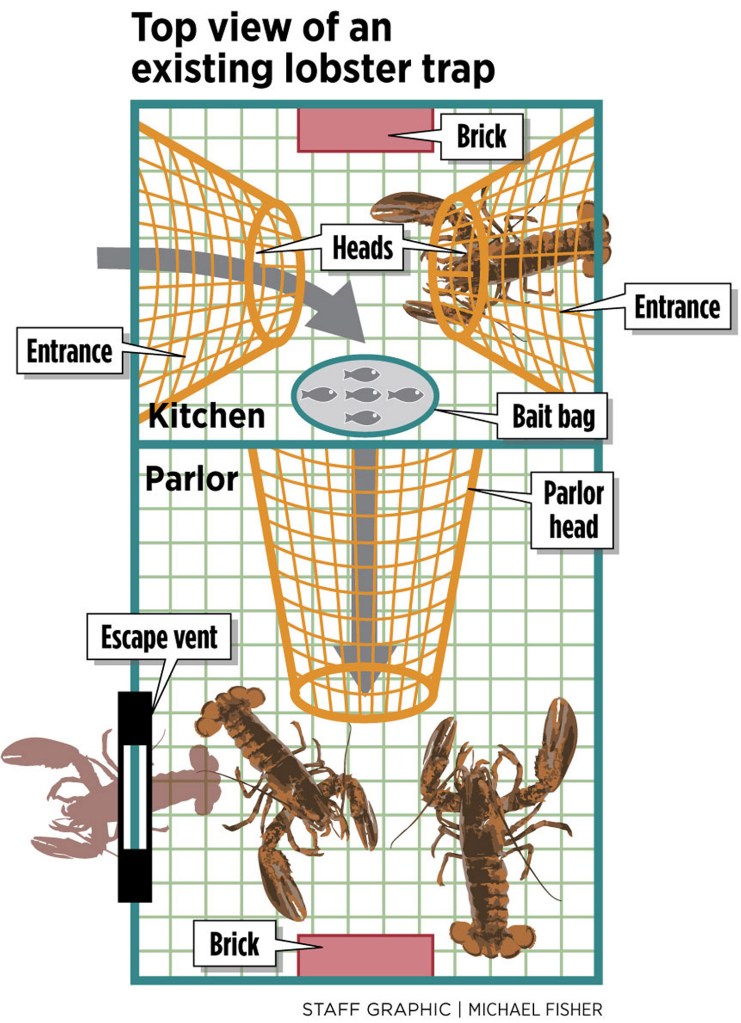

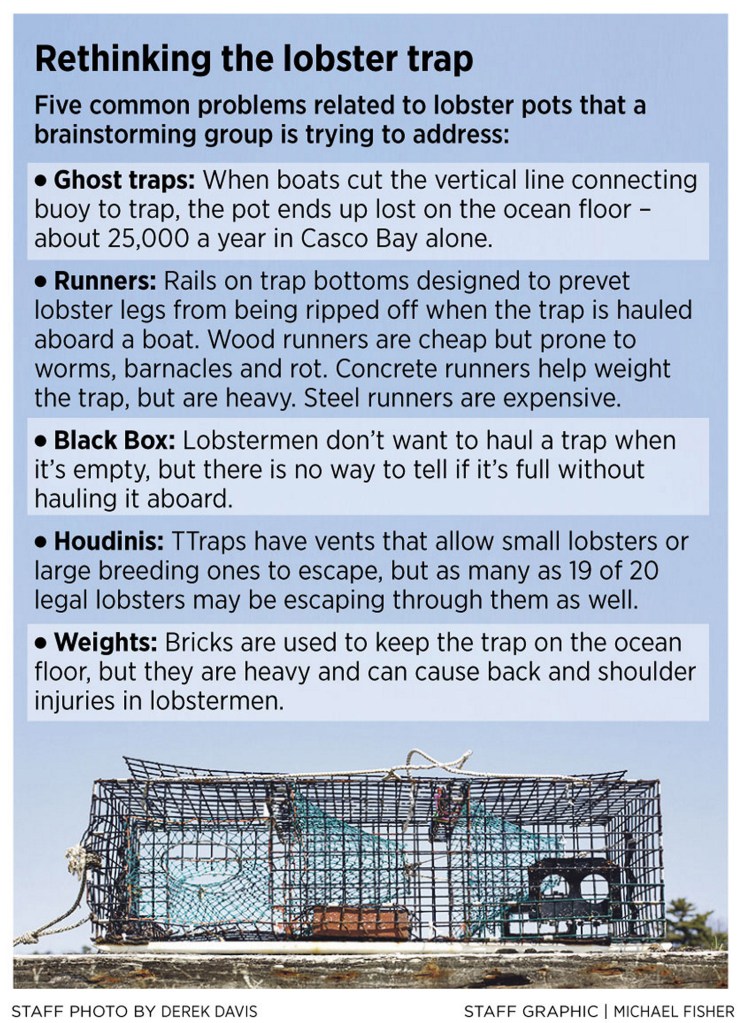

Zach Whitener, who grew up lobstering and now works at Gulf of Maine Research Institute, told the crowd of about 50 people who attended the “Lobster Hack” at the Open Bench Project at Thompson’s Point on Wednesday that the design of lobster traps hasn’t changed much over the last 120 years; only the materials to build them have. Steel has replaced wood. Biodegradable rings help lobsters escape lost traps. The vertical lines that connect traps to buoys now must break if a large sea mammal, like a right whale, becomes entangled.

“It’s an industry full of tradition,” Whitener said. “It’s pretty much the same trap we’ve been using for generations.”

The state’s $500 million-a-year lobster industry proves the current model is obviously working, but people who work or study the industry, like Whitener, acknowledge there is room to improve. The wooden runners intended to protect the lobsters from injury when hauled aboard the boat are subject to rot. Pots catch crabs and fish, not just lobster. Boats often clip the lines, causing traps to be lost. Lobstermen waste time hauling up empty traps. Nineteen out of 20 legally sized lobsters escape the pots.

The consequences of an imperfect trap extend beyond the state’s largest commercial fishery. For example, Whitener estimates that about 5 percent of the 500,000 lobster pots set in Casco Bay each year are lost, resulting in an ocean floor littered with metal cages. Some of those pots are filled with marooned lobsters that have grown too big to pull a Houdini and crawl out of the vent, or even slip out the escape hatch once the biodegradable rings give way.

“Traps cost $50 to $100 apiece,” Whitener said. “That’s lost money and time for a lobsterman, and lost lobsters, too, but imagine what it must look like down there. That’s 25,000 traps lost every year, piling up in the bay. That’s not good for the lobstermen, for the community, for anybody, and it’s certainly not good for the ocean.”

TECHNOLOGY AND TRAPS

Although Garmey is from Cape Elizabeth, and the Portland event was packed with her family and friends, her Chicago-based organization partners with local groups across the country to hold similar events. They are tackling the threat to Lake Michigan in Chicago and climate change in urban areas of Oakland, California.

The diverse group of would-be trap designers who attended “Lobster Hack,” which ranged from artists and lawyers to welders and, yes, fishermen, cracked a few craft beers and tried to come up with innovative ways to resolve some of these century-old challenges. They used cardboard boxes, wire, golf balls and anything they could find in Open Bench’s workshop to build prototype traps that would solve problems such as bycatch and rotted rails.

One group tweaked the escape hatch to include a flag that would float to the surface and mark the spot of a lost pot once the biodegradable rings gave way. Another suggested entry vents with flexible, one-way spikes, much like the ones that keep rental car users from backing out of a return lot, to prevent lobster escape. And another suggested developing a “black box” smartphone app that would monitor “pot full” Wi-Fi messages sent from pressure sensors in the bottom of a trap.

“Lobstermen don’t know it all, and scientists don’t know it all, either,” said Bob Morrill of South Portland, who used to work for the National Marine Fisheries Service. “I didn’t want to take over my group, being one of the experts, but I didn’t have to worry about it. All those new points of view, wow. I mean, an iPhone app. I’d never would have thought of that and I don’t know of too many fishermen who would think of that, either.”

At the end of the event, when the beer was flowing, participants agreed that none of the prototypes was likely to revolutionize trap design. Some of the ideas showed promise, but most wouldn’t work. Some were too expensive. Some violated one of the many regulations that govern the lobster industry. And some were too complicated and wouldn’t stand up to the wear and tear of the ocean or repeated use.

But that didn’t mean the Lobster Hack was a bust, Whitener said. Even if the ideas do not result in a new pot design, the event helped to educate the public about the challenges facing the lobster industry, which is a huge part of the state economy as well as its cultural heritage, he said. It also will help dispel some of the romantic myths, and outright misinformation, that surround lobstering, Whitener said.

“The more people know, the better,” said Monique Coombs, seafood program director at the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association. “Just getting people talking is good.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story