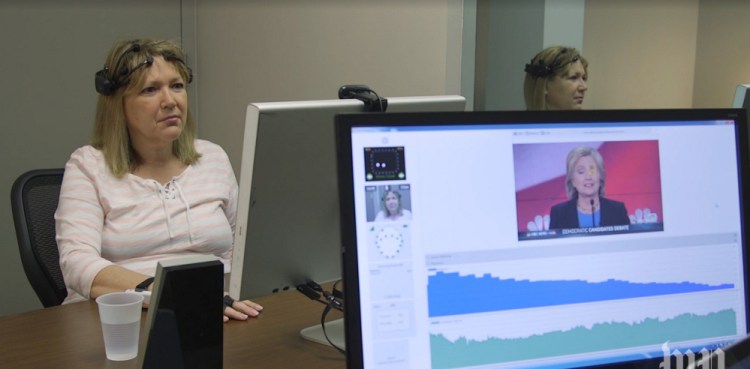

Neuroscientist Ryan McGarry swabbed a brain activity headset with saline solution and lowered it onto Brian Hazel’s head, connecting circular prongs gingerly to different spots on his skull.

Then he showed Hazel 40 minutes of presidential debates and commercials as Spencer Gerrol tried to read his mind. Which of the candidates did Hazel, an African-American real estate professional in his 40s, support?

Gerrol, founder and chief executive of creative agency Spark Experience, based in Bethesda, Md., stared through a one-way mirror from an observation room. “Trump,” he said five minutes into Hazel’s session.

Gerrol was right. “Donald Trump,” Hazel said after his session. “I’m all about jobs, and if I look at the whole field and who has created the most jobs, I think he would be able to do that better than anyone else.”

Spark’s experiment is leading a new method of human factors research, which asks test subjects to interact normally with everyday products or services while researchers track their emotional reaction and attentiveness. The agency gathers data from four tests – electroencephalograms, galvanic skin responses, eye tracking and microfacial recognition – to instantaneously determine which candidate a subject supports, down to the intensity of emotional response.

The firm gathered more than 30 test subjects from across the political spectrum in May. Their findings, released last week, show that what people feel and what they say they feel are rarely the same.

The experiment might be the closest the country gets to an explanation of this crazy presidential campaign without dissecting a brain.

Instead of placing participants in focus groups or asking them to fill out a questionnaire, experimenters harvest data directly from the brain using technology called “BrainWave.” Companies such as Nielsen and Affectiva conduct similar testing, which can gauge the effectiveness of advertisements and viewer response to TV shows and movies.

“This isn’t science fiction,” Gerrol said. “I can’t read your thoughts, but I can read your emotions.”

The methodology has particular application this election cycle because voters’ responses have been so unpredictable. Spark’s study may have provided some answers, namely that test subjects may subconsciously lie when they tell people what political messaging works and what doesn’t.

“If you ask somebody what they’re feeling, you’re not going to get a very accurate response. Emotion is subconscious,” Gerrol said. “The idea is to measure emotion without asking.

“When people make decisions, it’s tempting to think there’s a lot of rational thought. That’s not really true. You can’t have decisions without emotion.”

The political testing found that Trump held voters’ attention exceedingly well, at a 7 on a 10-point scale. That’s better than even the most popular TV commercials. When Trump hurled an insult, they laughed it off and moved on. But his references to the Islamic State and overseas trade wars stirred up fear, the most intense emotion that humans experience.

Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton averaged a 4 out of 10. Voters were bored with her résumé, results show, which she repeats time and again.

Those are results that Gerrol says traditional polling methods won’t capture because they ask subjects to interpret their own emotions, which inevitably get filtered.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.