BRUNSWICK — The Navy has tested several dozen residential wells on the outskirts of the former Brunswick Naval Air Station for the presence of a chemical suspected of posing health risks.

Officials from the Navy and the Maine Department of Environmental Protection say the voluntary water tests are aimed at determining whether the chemicals – perfluorinated compounds, or PFCs – are migrating in groundwater beyond known contamination sites on the former air base. Formerly a common ingredient in flame suppressants and household products such as nonstick cookware, PFCs have been shown to affect organ function in animals and are being intensely studied for impacts on humans.

The Brunswick water sampling comes one year after officials in New Hampshire began testing blood samples from individuals potentially exposed to PFCs in a public water well in Portsmouth located near the former Pease Air Force Base. Unlike in New Hampshire, where the chemicals’ discovery caused considerable controversy, PFCs have not been detected at elevated levels in Brunswick’s public water supplies.

“There are no situations that we are aware of in Maine that rise to that level of concern,” said Kerri Malinowski, who oversees the DEP’s Safer Chemicals program.

The Navy has yet to release the testing results. However, the DEP says none of the samples it tested for quality assurance purposes in cooperation with the Navy – about 25 percent of the total – had PFC levels above the health levels recently established by federal health officials.

“We anticipate the remaining samples will have similar results,” Malinowski said in a statement.

TEST RESULTS EXPECTED THIS MONTH

PFCs were widely used from the 1950s to the 2000s, so much so that the chemical’s various compounds show up in the blood of nearly every human in testing and are widespread in wildlife as well.

The chemicals provided the nonstick surface to Teflon and other cooking products, were key ingredients in 3M’s Scotchgard stain-resistance technology and were common in the foam spray used by firefighters – as well as automatic fire suppression systems – at airfields and industrial facilities. In fact, PFCs were still used as anti-grease linings in microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes and other food packaging until January, when the Food and Drug Administration banned them – five years after U.S. companies stopped manufacturing the chemicals under an agreement with federal regulators.

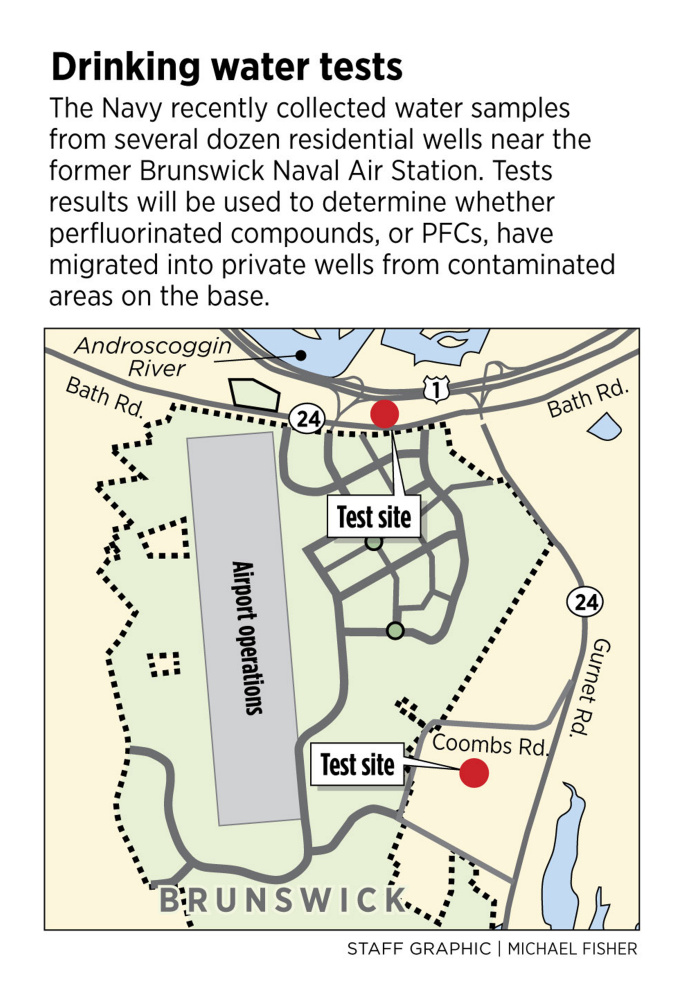

The Navy collected water samples from homeowners in a rural neighborhood nestled along the former Navy base’s southeastern edge as well as in an area across Bath Road and Route 1. The core of the sampling area extended along Coombs Road, which meanders roughly parallel to Route 24 and features a mix of old farmsteads and newer construction on large, often wooded lots.

Samples were collected from April through June, and Navy officials told participating homeowners that they would likely be notified of results in July.

A Navy spokesman said more detailed information on the tests – including the number of samples collected and any results – was not available Friday.

Dan Moore was among those waiting to hear the results from the well at the home he and his wife have owned for about three years. Moore said he was happy to participate in the testing, saying he hasn’t noticed any issues with the water and doesn’t believe there are high levels of the chemicals in the water. But standing outside of his modest single-family house, Moore said it is always preferable to know for sure.

“It should be a couple of weeks,” he said.

MILLIONS SPENT ON BASE CLEANUP

Several other neighborhood residents who did not want to be identified said they were also waiting for official notification from the Navy but said they were pleased officials were testing local waters. For some local residents, it is only the latest water test to detect potential toxins leaching from the soil or underground water tables on the former Navy base, which officially closed in May 2011.

The Navy has spent more than $100 million investigating and cleaning up pollution on the roughly 3,100-acre property and still operates a water treatment and monitoring system in one contaminated area known as the “Eastern Plume.” The Navy transferred much of the base to either the town of Brunswick or the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority, which is seeking to redevelop the base now known as Brunswick Landing.

Elevated levels of PFCs have been found at several areas of the former Navy airbase, most notably around a fire training area on the base and in the Eastern Plume near Merriconeag Stream. PFC contamination was also found near the airport apron as well as around a building, No. 653, where fire suppressant foam deployed following a lightning strike.

“The areas where (PFCs) are present in groundwater above the EPA provisional health advisory levels are located in areas where groundwater is not used as drinking water,” the Navy said in an April fact sheet distributed to homeowners. “However, properties north of the former base may use groundwater as drinking water; therefore, sampling in this area is planned. Similarly, while the use of groundwater at the Eastern Plume is restricted, there are residential homes located near this area that are using groundwater as a drinking water source, thus additional sampling is planned.”

The Navy pledged to provide homeowners who have contaminated wells with alternate water sources, such as bottled water, for drinking and cooking “at no cost to the property owners until a long term solution can be put in place.”

The DEP’s Malinowski said the department is also working with the Department of Defense to sample water near the former Loring Air Force Base in Limestone and Navy facilities near Cutler.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classifies PFCs as a “contaminant of emerging concern” and earlier this year set a “health advisory” level of 70 parts per trillion for certain PFCs. Such advisories are only recommendations – not legally enforceable levels – based on existing scientific studies, however. Studies of the chemical’s effects on human health are ongoing.

CONTAMINANTS IN OTHER AREAS

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences said in a PFC fact sheet released this month that animal studies have shown that some PFCs disrupt activity in the hormone-regulating endocrine system, affect organs such as the liver and pancreas, reduce immune system function and can cause developmental problems in the offspring of rodents that were exposed to the chemical.

“Data from some human studies suggests that PFCs may also have effects on human health, while other studies have failed to find conclusive links,” reads the institute’s fact sheet. “Additional research in animals and in humans is needed to better understand the potential adverse effects of PFCs for human health.”

PFCs have emerged as an issue near military bases across the country, with contamination on a larger scale than that seen in Brunswick to date.

In May 2014, the city of Portsmouth shut down one of its public water system wells after tests revealed PFC levels that were up to 35 times higher than the 70 parts per trillion advisory level later set by the EPA. Blood testing of more than 1,500 individuals who worked on, lived on or attended child care facilities on the former Pease Air Force Base found higher PFC levels than in the general population. But the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services report did not assess the potential health effects of PFC exposure.

Meanwhile, in Colorado state health officials recently recommended that some people on public water systems near Colorado Springs – the site of the U.S. Air Force Academy and Peterson Air Force Base – switch to alternate water supplies because of PFC contamination. As many as 80,000 people in the Colorado Springs area are served by drinking water systems contaminated by PFCs, according to news reports.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.