“This Is a Portrait If I Say So,” an exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, is premised on the idea that people may be represented by qualities other than physical likeness. Western visual culture has long embraced that idea. Story subjects are usually recognized by their attributes – not their faces. “Attribute” is in fact the word for the metaphorical markers that have always accompanied the Christian saints, and Western painting grew up in the Church: The guy tied to a post and shot through with arrows must be Saint Sebastian, the old man with a lion is Saint Jerome, and so on.

Secular stories also feature the props of myth and moral: The hatchet-holding boy next to the chopped cherry tree is George Washington.

With modernism (and arguably the advent of photography), however, the realistically painted portrait became a complicated and highly charged object. Painterly realism, after all, was the stuff of the academy – and if there was one gathering point for the modernists, it was the shunting of the top-down institutionalized culture of the academy.

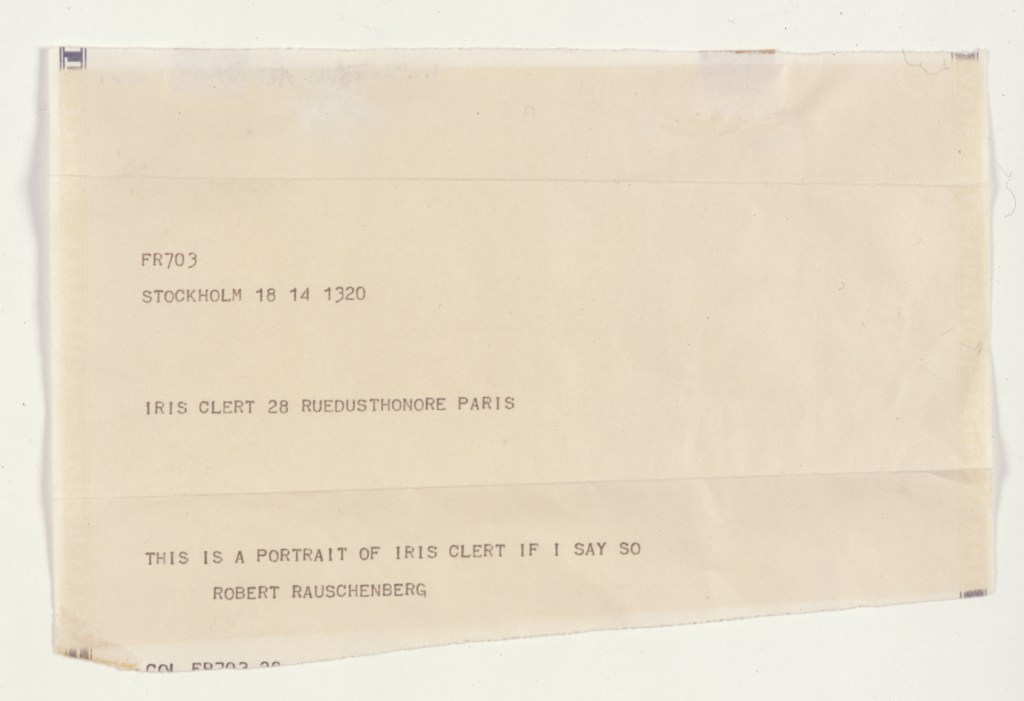

At Bowdoin, the first piece is Robert Rauschenberg’s last-minute masterwork of conceptual art from which the exhibition gets its title. Preoccupied with a major exhibition in Sweden, Rauschenberg forgot he had promised to make a portrait for the opening of Iris Clert’s gallery in Paris in 1961. So the American artist sent a telegram from Stockholm that simply stated: “THIS IS A PORTRAIT OF IRIS CLERT IF I SAY SO.”

Whether you’re a fan of conceptual art or not, the piece is certainly a conversation starter. It references its subject – Iris Clert – and lays clear the author and his intentions. At the most basic level, it takes aim at the heart of representation: convention. A word, after all, only has meaning if we agree it does. For something to be recognized as referring to something, it has to cross the threshold of convention. In the study of signs known as semiotics, there are three main paths this can take: An icon looks like the thing (traditional painting); an index has a physical relation to the thing (a fingerprint); and a symbol can be an arbitrary convention (the word “dog” or the idea that a red octagon means “stop”).

“This Is a Portrait If I Say So” covers a tremendous range of content because it looks to creative, powerful and surprising notions of portrait from the past 100 years. While a few modes like iconography, description, metaphor and association bubble to the top, the exhibition’s success rides boundary-pushing possibilities. This makes for a challenging show that requires viewers to rethink practically every piece they see.

The star quality of the work makes that effort particularly rewarding and helps give the work context through prior knowledge of the artists. For example, Bowdoin has brought from Minnesota one of Marsden Hartley’s portraits of a German officer, part of his brilliant cubist series that became the high-water mark of American modernist painting. This painting alone is worth the trip, but it is accompanied by a no less brilliant Hartley portrait of Gertrude Stein. While much of the work is fresh from the edges, the well-known artists in “This Is a Portrait If I Say So” facilitate the project of recognition – the very subject of the show: Pablo Picasso, Yoko Ono, Jasper Johns, Georgia O’Keefe, Marcel Duchamp, Jim Dine, Ross Blechner, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Mel Bochner, Dan Flavin, Charles Demuth, Alfred Steiglitz, Robert Indiana and Florine Stettheimer among many others.

The challenge of the exhibition lies in the range of the works, each of which not only yields its own subject, but its own internal logic. Fortunately, the works are accompanied by insightful labels and an exemplary (and hefty) scholarly catalog.

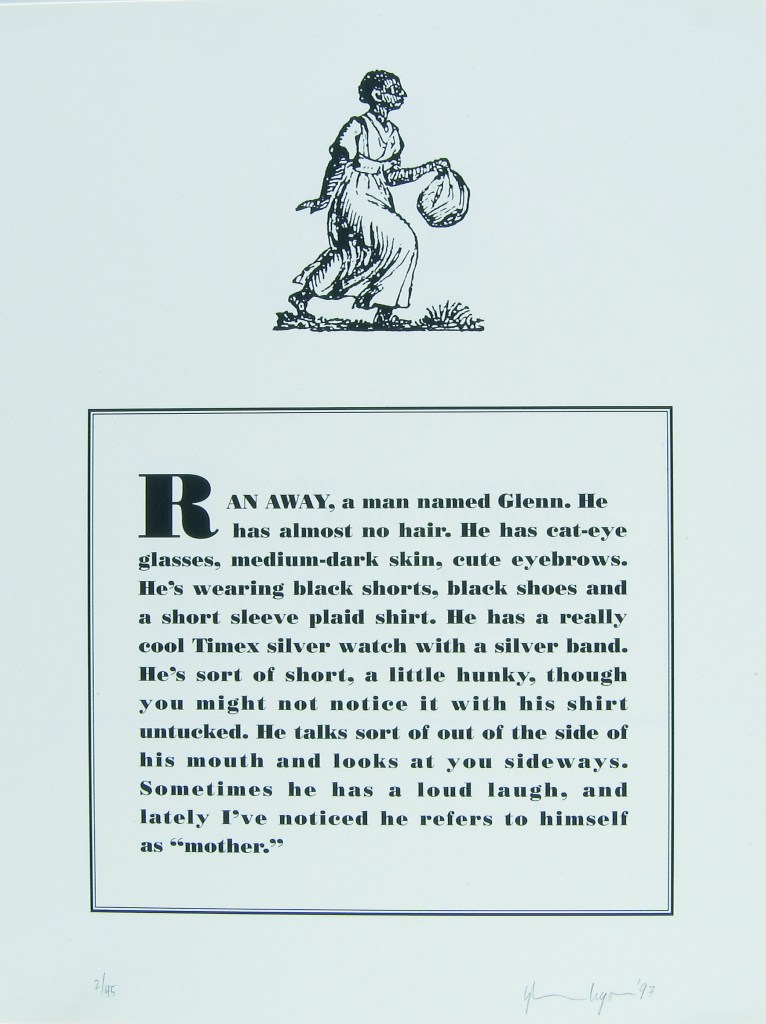

Much of the work is witty. Dan Flavin’s “Barbara Roses” for example, is an exquisite potted light fixture in the shape of a rose – which he presented to his critical champion, Barbara Rose. Jason Salavon’s video installation laughs at a compendium of his own Google searches. Janine Antoni’s “Butterfly Kisses” follows the magical realism notion of compelling specificity: Each side of a sheet has 1,124 marks made by her heavily mascaraed eyelashes; it looks like a girlishly magical – and beautiful – dark Mark Tobey. Roni Horn’s oblong steel ball is unlikely, but the description of how the subtly irregular object came to remind her of herself is compelling – and then seeing the oblong shadows dancing around it makes the theatricality of it fascinating: Is it hiding its quirks under the distorted shadows, or are they furthering the non-spherical effect? Glenn Ligon’s deployment of friends’ descriptions of him in the form of runaway slave notices (a bona fide genre at one time) sting with echoes of unsaid assumptions about how Americans were once invited to doubt the free status of anyone who appeared to be of African descent. Man Ray’s blend of cartoonish joking and savvy symbolism leads from the initial giggles to a subtle art compendium, along with a handprint that leads back through Rauschenberg’s fingerprint to the notion of traces and deductive evidence.

Particularly strong works include Ross Blechner’s gay pride flag painting with a star of David quietly embedded near the top. It powerfully converts the diversity symbol into a painterly field and creates havoc with perspectives and priorities. LJ Robert’s single-strand embroidery reads like a scrapbook of late ’80s symbols in the vein of ACT UP; its echoes are ghostly and dangerously powerful still. Byron Kim’s grids of color panels seem to represent color palettes for the skin of individuals, most notably his son when he was 12 months old. In this context, we can no longer miss what Kim’s approach intentionally leaves out.

“This Is a Portrait If I Say So” is an excellent launching point for thinking about how art works. And because of that, it is a particularly powerful introduction to many of the critical ideas taken on by the modernist painters in particular. It is an exciting exhibition, informative, entertaining and challenging.

From the start, it is loaded with witty irony. Rauschenberg insists, “THIS IS A PORTRAIT OF IRIS CLERT IF I SAY SO.” But does he ever actually say so?

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.