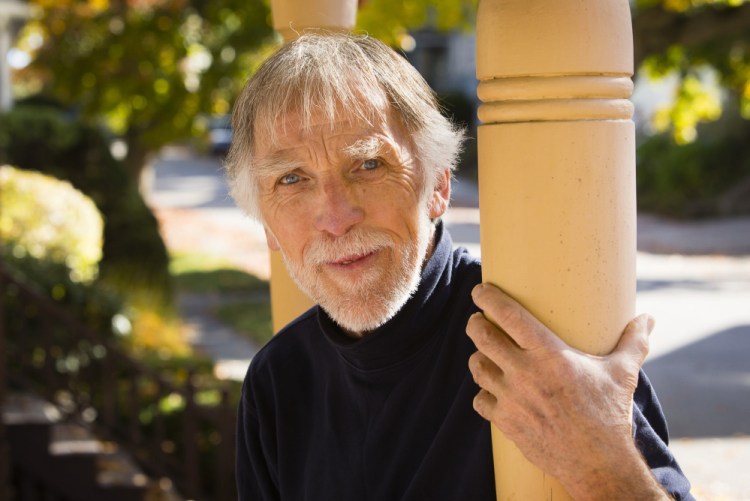

In 1967, Rob Boudewijn was an immigrant from the Netherlands living in California and learning toward becoming a veterinarian.

“Being a new immigrant, I didn’t know much of the rules,” he recalled. “I went to the Army recruiter and I told them I wanted to be a veterinarian.”

Boudewijn had been working at the San Francisco Zoo. He wanted to get his veterinary degree so he could help large animals thrive, even in captivity.

Instead, he became a soldier.

“They said it was great that I wanted to be a veterinarian, and they could help me do that. But obviously they don’t have a veterinary school in the Army. I was a very naive young guy,” he said.

Instead, Boudewijn was shipped off to Vietnam, where he worked as an operating room technician. From January 1967 to October 1969, Boudewijn served as a corporal in the U.S. Army, working in Texas and North Carolina as well as Vietnam.

In 1969, on his way back from Vietnam and during a stopover in Hawaii, Boudewijn became a U.S. citizen.

When he returned to his home in California, Boudewijn briefly considered resuming his work with animals. “But the war had changed me so much,” he said. “When you’re a veterinarian, you have to be able to read animals, and I felt that I had lost that.”

Instead, Boudewijn decided to shift his focus to another type of creature in need. He understood what veterans had been through during war, and he could see how hard it was for many of them to return to civilian life. “I wanted to help people,” he explained.

The 1970s society Vietnam vets were returning to wasn’t familiar with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“PTSD was not a term,” Boudewijn said. “They called it post-Vietnam syndrome.”

The condition wasn’t well understood, but psychiatrists, doctors and veterans all agreed that something was wrong. Something needed to be fixed.

Boudewijn became involved with an organization in California called Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Although he didn’t have formal psychiatric training, he began hosting group sessions with other veterans.

“There was no formality,” he remembers. “We would get together, in local houses, bars, or wherever we could find a space, and just talk. A lot of the guys I worked with were dealing with guilt. Some were dealing with injuries. Then there were the drug and alcohol problems. We wanted to find a way to prevent people from hurting themselves, abusing drugs or committing suicide.”

Over time, the psychiatric community became more involved in treating veterans with PTSD. Soon, Boudewijn realized there was another way he could help, and he got his physician assistant license.

These days, Boudewijn lives in Portland and works at Maine General in Augusta as a physician assistant in the emergency department. He returns to San Francisco, the city he calls his “first love,” once a year, where he reconnects with old friends. But his wife, Gretchen Hill, whom he married in 2001, and his work are in Maine now.

But while he’s switched coasts and changed jobs, Boudewijn has never lost his desire to speak out against war. He remains a member of Amnesty International. He attends demonstrations in Portland, and often, when something is bothering him, he will write a letter to his local representative or to the local newspaper.

Boudewijn said he doesn’t identify as a hippie, but rather as a “serious guy” who wants to make the world a safer, less violent place.

“I saw the brutality of war. I saw the number of casualties from America, Australia and Vietnam,” he said. “It wasn’t that I was anti-U.S. occupation; it’s that I don’t think war is a way to solve problems.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.