In town halls, police departments, churches, county jails and hospitals across Maine, the talk is what to do about heroin.

From folding chairs in Down East community centers to pews in southern Maine churches, community leaders and activists are working to address a public health crisis that state government was slow to recognize and address.

Grass-roots efforts have aimed to fill the void left by state policies that made it more difficult for addicts to get treatment despite the rising overdose deaths, 376 in 2016, or about one death per day.

“I didn’t need a revelation. It’s happening all around us,” said the Rev. Todd Bell, pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Sanford, which is starting a faith-based treatment program this spring.

But is Maine’s approach working?

Since December, state government has begun to devote more money and resources to the opioid epidemic, including $5.4 million for the uninsured, and to reduce MaineCare wait lists for treatment. A tough new state prescribing law passed last year intends to curb the flow of prescription opioids – blamed for fueling the crisis – and prevent people from getting addicted in the first place.

To understand the state of Maine’s often conflicting views of the crisis, a recent radio interview with Gov. Paul LePage offers insight.

Speaking on WVOM in Bangor last month, LePage asserted that opioid treatment was readily available and free for the uninsured.

Not true.

Addiction specialists, hospitals and doctors’ groups report that access to treatment is nearly impossible for the uninsured. And they account for about 40 percent of those who are seeking help, according to treatment centers. Maine – because of LePage’s vetoes – has also refused to expand Medicaid, which would open up drug treatment to thousands who are now uninsured.

Rob Gay knows personally how hard it is to find treatment with no insurance. After a suicide attempt in August and years of opioid abuse, Gay tried for six months before he finally got into a long-term residential treatment program operated by Milestone Foundation in Old Orchard Beach. The foundation has three beds for the uninsured.

“I definitely lucked out,” said Gay, 34, of Gardiner. “The wait was nerve-racking, and I lost hope sometimes. It’s so hard to get in anywhere.”

Rob Gay, 34, of Gardiner prays at Milestone Foundation’s residential treatment program in Old Orchard Beach. A longtime addict who’s struggled to get help because he has no insurance, Gay finally secured one of only three beds at Milestone reserved for the uninsured.

Gay said he easily could have been one of the hundreds who died of a drug overdose over the past few years.

More than twice as many people in Maine died from drug overdoses – 376 – than from vehicle accidents in 2016.

Will the varied efforts – by the state, communities, police, churches, the health care industry and treatment providers – be enough to reverse the tide of overdose deaths?

Some are skeptical Maine is doing enough – and that the mixed messages are weakening the response.

Health care experts contend that the LePage administration – despite recent attention to treatment – has not devised a comprehensive response to the problem, even as the overdose rate accelerated over the past three years.

Steve Cotreau, program manager for Portland Community Recovery Center and a coordinator for Operation Hope, a Scarborough Police Department program that helps connect addicts with recovery, said inaction by the state led to Operation Hope starting in 2015. Most of the program’s placements are out-of-state because of the lack of treatment resources in Maine.

Cotreau said he suspects the vacuum caused by the state’s tepid response led to the launch of other local and regional efforts.

“If the state had done more, there wouldn’t have been this great need,” Cotreau said. “People wanted to do something. But these are just Band-Aids trying to cover a gaping wound. We need huge interventions, and they’re not happening yet.”

VITAL SIGNS: A year after the legislature passed a law in April 2016 to make Narcan available in pharmacies without a prescription, the life-saving antidote still isn’t available because the state Board of Pharmacy hasn’t written the rules governing sales.

Gordon Smith, executive vice president of the Maine Medical Association, which represents doctors before the Legislature, said while it’s difficult to predict overdose trends, he believes deaths could continue to climb over the next few years. He said the response has improved but is not yet robust enough.

“I’m not confident that there’s going to be improvement anytime soon in overdose deaths,” said Smith, who has worked for more than a year on new prescribing standards and trying to persuade more doctors to treat addiction.

Even in Vermont – hailed by national addiction experts as a model on how to address the opioid crisis – overdose deaths are still climbing. Vermont had 155 deaths from heroin or other opioids in 2016, up from 94 the previous year. Since 2014, Vermont has devoted resources and committed to a model to deliver treatment to its residents.

Meanwhile, grass-roots efforts in various parts of Maine are cropping up, from Sanford to Portland, Lewiston, Bangor, Augusta and other cities and towns. Many of the efforts are to expand medication-assisted treatment – including Suboxone and methadone – which curbs cravings and is widely considered the most effective treatment for opioid addictions.

GETTING ASSISTANCE TO MAINE’S UNINSURED

One of the most vexing problems is connecting the uninsured to treatment, because opioid addicts often lose their jobs and their insurance while grappling with addiction. LePage has vetoed several attempts to expand MaineCare, the state’s version of Medicaid, which would open up treatment options for thousands by allowing more low-income Mainers to qualify for insurance. The administration instead has promised to spend an additional $5.4 million to help the uninsured and those receiving MaineCare, providing medication-assisted treatment to an estimated 750 more people.

Experts call it a start but say much more needs to be done.

For instance, Medicaid expansion would provide insurance to 80,000 Mainers, although it’s unknown how many of the newly insured would take advantage of substance use treatment services. Medicaid expansion will go before voters in a November referendum.

About 25,000 to 30,000 Mainers with addiction can’t get the help they need, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. About 15,500 people received treatment for opioid addictions in 2015, according to state statistics. The total number of people with opioid addictions is unknown.

Other steps have also constricted treatment options in Maine.

Since 2012, the administration has cut methadone reimbursement rates, limited eligibility for methadone treatment to no more than two years without prior authorization and removed thousands of adults from MaineCare. Leaders of methadone clinics say Maine’s $60 weekly reimbursement rate for methadone is too low and was a major reason that a Sanford methadone clinic closed two years ago. New requirements imposed upon methadone clinics in late 2016 are also limiting access, said Jim Cohen, an attorney who represents the clinics. About 4,000 Mainers receive methadone treatment.

LePage also vetoed bills to expand access to naloxone, a life-saving antidote to overdoses.

The Legislature finally overrode one of those vetoes to make naloxone available to family members and friends of drug users.

Meanwhile, a bill sponsored by Rep. Karen Vachon, R-Scarborough, would pump $6.7 million into medication-assisted treatment, giving access to about 1,000 Mainers and adding more muscle to the administration’s proposals to expand treatment.

Vachon said the crisis is so acute that it’s time for a more aggressive response.

“The proper treatment requires a lot of big cost,” she said. “It’s a tough disease to tackle.”

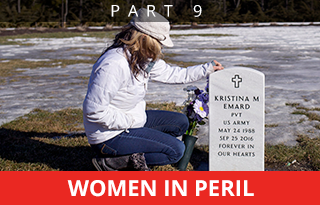

Jennifer Storer, 27, of Lewiston, is in an out-patient, medically assisted treatment program through Grace Street Services. Storer started using opiates at age 15 and was shooting heroin by 17. She had been in recovery before, but said that Suboxone is like her insurance. “As soon as I have a thought about doing heroin I take my Sub,” she said. “I know that even if I want to do some heroin, it wouldn’t have any affect on me.”

MEDICAL COMMUNITY RESPONDS: ‘WE CAN DO BETTER’

The medical community has also been slow to react, a point that has been made by the Maine Medical Association and several doctors who are addiction specialists.

“With one death daily, it’s a disgrace that only 5 percent of Maine primary care physicians have obtained the DEA waiver to treat addiction. We can do better by our patients,” the association said in a recent Facebook post.

Maine is far from alone on that count, said Dr. Norman Wettereau, chairman of the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s family practice work group. Wettereau said in most states, the response to the opioid crisis was weak.

“I am infuriated with the medical profession,” said Wettereau, an addiction specialist in Rochester, New York. “They were a major cause of the problem, and they didn’t want to do anything about it.”

He said Vermont, New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island are among the states that are doing a better job of providing treatment and reducing the prevalence of opioid prescriptions.

A “hub and spoke” system launched in Vermont two years ago is being used as a model for Maine. The idea is to have a central location – a clinic, usually – for the most acute patients with substance use disorder. Those who stabilize are transferred to other programs, usually primary care practices.

The system will require more doctors who are trained and willing to prescribe Suboxone, a difficult problem to solve but one where progress is being made, Smith said. This year nurse practitioners and physician assistants acquired the authority to prescribe, which should help alleviate the shortage, Smith said.

Gay, who recently made it into the Milestone treatment program, said Suboxone has helped him, although his goal is to eventually taper off of the medication. Like many heroin users, he started on prescription painkillers. Although he had taken other drugs in high school, he said his opioid addiction started when he injured his shoulder playing hockey and his doctor prescribed him Vicodin.

Gay said shortly before his suicide attempt, he was arrested for stealing and pawning guns so he would have money for drugs.

“I knew I liked the feeling it gave me,” he said. “I felt like Superman.”

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants now have the authority to prescribe Suboxone.

NEW PROGRAMS LAUNCHED ACROSS THE STATE

Local and regional efforts to combat opioids are springing up all over the state, including in Portland, Augusta, Bangor and other places.

Many times, the new programs encounter barriers caused by Maine’s lack of treatment resources.

At Nasson Health Care in Sanford, the clinic is expanding Suboxone treatment, but the current financial model makes it difficult to do so to a great degree. The uninsured must pay out-of-pocket, and Suboxone costs several thousand dollars per year. If 40 percent of the patients treated were uninsured, the cost would be unsustainable, said Nasson executive director Mary Sabol, because the clinic would have to foot the bill.

“If we (Nasson) tried to pay for that many uninsured, it would break our bank,” Sabol said.

Nonetheless, health systems are rolling out new programs despite the obstacles.

MaineHealth, the largest health care network in the state and the parent company of Maine Medical Center, is establishing a hub and spoke model in health networks across the state.

In Augusta, Alane O’Connor, a Waterville nurse practitioner, is launching a program with MaineGeneral Medical Center in which several doctors staff a clinic for a few hours each month, seeing patients and writing Suboxone prescriptions. Once the patients are stabilized, they are transferred to primary care practices.

The Maine Health Access Foundation is spending $800,000 over the next two years on $75,000 grants that will help communities across the state launch medication-assisted treatment.

In the Bangor area, a new program in Old Town operated by the Penobscot Community Health Center this spring will start serving about 200 patients. Bangor is also opening a detox center, the second in the state after Portland’s Milestone Foundation.

Grace Street Services, a medication assisted treatment provider, is working with several partners to open a facility in Sanford.

Portland has formed a coalition seeking funding through a federal program, while Buxton, Gorham, Windham and Westbrook are collaborating on a program that connects people with treatment programs. The Cumberland County Jail is starting an opioid treatment program for inmates, and York County is working on opening a long-term, residential treatment program.

Eric Haram, an independent consultant who formerly ran a treatment program at Mid-Coast Hospital in Brunswick, said he now travels the state, explaining how to start Suboxone programs, and he’s seeing a lot more interest in recent months.

“There’s been a seismic change, a cascading effect,” Haram said. “People are starting to get it, and are saying, ‘Yeah, let’s do this.'”

Smith, at the Maine Medical Association, said the state’s recent decision to fund more treatment represented “a huge turnaround in the administration’s philosophy” and would help address the mounting toll of addiction. But he also said he’s not convinced that Maine has found a way yet to make a significant impact on the heroin epidemic.

“I’m afraid there’s a lot of people in trouble,” he said, “and we still haven’t yet devoted enough resources to this.”

This story was updated at 4:09 p.m. on April 13, 2017 after the Maine Attorney General’s Office revised its preliminary estimate of the number of drug overdose deaths in 2016.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.